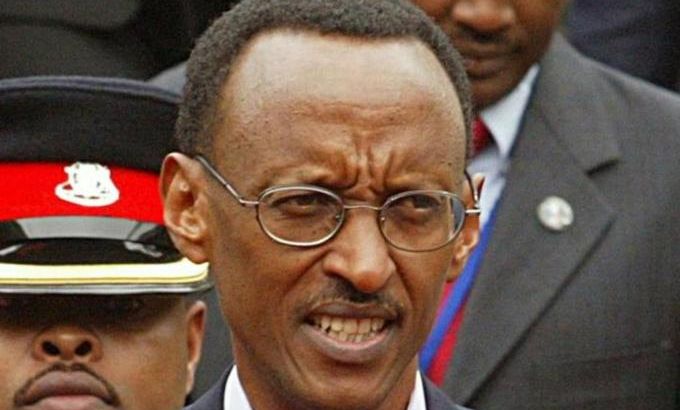

Kagame

Twenty years after Rwanda’s genocide, should President Paul Kagame be seen as a saviour or a dictator?

It is still difficult to comprehend the barbarity of the killing frenzy that swept through Rwanda 20 years ago.

Somewhere between 800,000 and one million people were slain in just 100 days. They were killed by machetes and clubs, by guns and grenades, and hacked to death at road blocks. Entire families were massacred in their homes; women were systematically raped before being murdered; children were slaughtered without pity or mercy.

This all happened in a gigantic spasm of tribal hatred and fear whipped up by the country’s elite, who set its Hutu majority population against its Tutsi minority in a cynical gambit to retain power, and all – to the world’s enduring shame – without the international community lifting a finger to stop it.

That the nightmare did end, that the savagery did not continue until every one of Rwanda’s Tutsi civilian population was wiped out, is due more than any other single individual to the country’s current president, Paul Kagame.

As the head of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, a rebel army formed largely from Tutsi exiles in neighbouring Uganda, Kagame had played a leading role in the three-year-old Rwandan civil war, supposedly settled with a peace agreement in 1993.

When the massacres began a year later, Kagame and the RPF restarted the war and eventually brought the genocide to a close with a complete military victory – forcing the government and its supporters over the border into Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo, or DRC).

A rebirth of a nation

Over the subsequent 20 years, the last 14 of which have been under Kagame’s presidency, Rwanda has been reborn as one of Africa’s most unlikely success stories.

This small landlocked country is now one of the safest on the continent; the economy is thriving; 98 percent of the population has access to health-care; the average life expectancy has doubled; there is free education; and many of the roads are as good as any in Europe.

In many ways, it is a truly remarkable narrative, a triumph – say Kagame’s supporters – of reconciliation and reconstruction that would have been unthinkable two decades ago.

But the narrative has a dark side. Kagame’s uncompromising belief in his own vision has undoubtedly been the force behind many of Rwanda’s achievements, yet it has also attracted significant criticism.

Over the years he has earned a reputation for cracking down hard on critics, of brutally suppressing dissenting voices in the media and even among his own political party. Some of his opponents have been forced to flee the country, others have been imprisoned, some have been killed in exile overseas – blame for which many are convinced should lie at Kagame’s door.

He is also accused of continuing to meddle in the affairs of Rwanda’s neighbours – especially the largest, the DRC. Ever since the Rwandan massacres, the eastern DRC has been in a constant state of turmoil, largely due to the mass arrival of Rwandan Hutu refugees in 1994, many of them génocidaires, who fled as Kagame’s forces advanced and took up station in refugee camps along the border – among displaced Tutsis they had previously tried to kill. The Hutu refugees subsequently launched their own bitter insurgency against the new Rwandan government and remain active to this day.

Two Rwandan invasions in the 1990s emptied the camps and most of the civilian refugees returned home, but Kagame has been unapologetic in his support of militia groups who have carried on the fight against his enemies in the DRC, at considerable cost to that county’s peace and stability and to the great frustration of the international community.

So how, 20 years after Rwandan genocide, should Kagame be seen? As a saviour? As a dictator? Should his achievements and his failings be judged solely in an African context or against a set of universal principles that should apply to all? Is it even possible to come to any meaningful opinion about him without having an understanding of how and why his country fell so low two decades ago and how far it has climbed back since?

Journalist Sorious Samura experienced another of the continent’s devastating conflicts at first hand – the civil war in Sierra Leone during the 1990s – and has seen that country struggle to fully recover. People & Power sent him to Rwanda with film-maker Clive Patterson to assess Kagame’s place in Rwandan and African history.

|

People & Power can be seen each week at the following times GMT: Wednesday: 2230; Thursday: 0930; Friday: 0330; Saturday: 1630; Sunday: 2230; Monday: 0930. Click here for more People & Power |