Turkey’s foreign policy: From past to potential post-Erdogan era

Erdogan’s independent foreign policy put Turkey on the map – the opposition’s may be far more muted.

In August 2019, after inspecting the cockpit of Russia’s then-new fifth-generation Su-57 fighter warplane, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan asked his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, if it was for sale.

“Yes, you can buy it,” Putin responded with a smile, as he enticed Erdogan with Russia’s latest foreign jets at the MAKS-2019 international air show outside Moscow.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTurkey’s leader Erdogan cancels third day of election appearances

Turkey’s pro-Kurdish party backs Erdogan’s rival for president

Erdogan returns to Turkey election campaign trail after illness

The duo, donned in dark suits and dark shades, toured other warplanes and then took a break to eat ice cream cones.

“Will you pay for me?” Erdogan asked Putin, nodding towards the cones, to which Putin responded, “Of course, you’re my guest”.

The exchange exemplified the renewed closeness of Turkish-Russian security relations after a difficult period, during which Turkey downed a Russian fighter plane that it said had strayed across the border from Syria. But it also showcased Erdogan’s personality-driven approach to foreign policy during his two-decade rule.

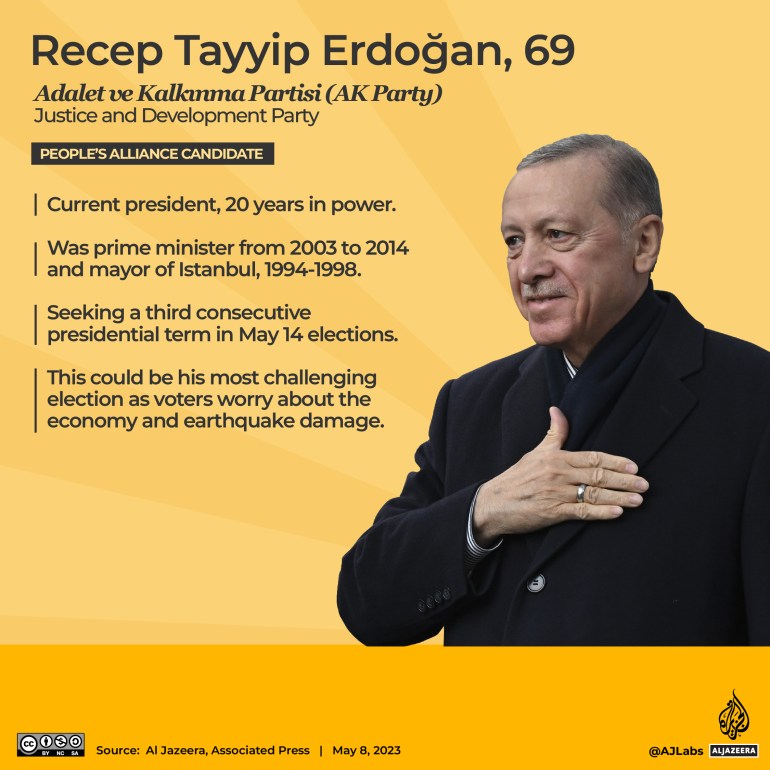

As Turkey has sought to position itself as a regional heavyweight, the Justice and Development Party or AK Party leader’s confident, if confrontational, style has shaped the country’s international relations.

Turkey has certainly grown more influential – not just across the Middle East, but also Africa and Europe, with its prominent role in mediating between Russia and Ukraine a particular example.

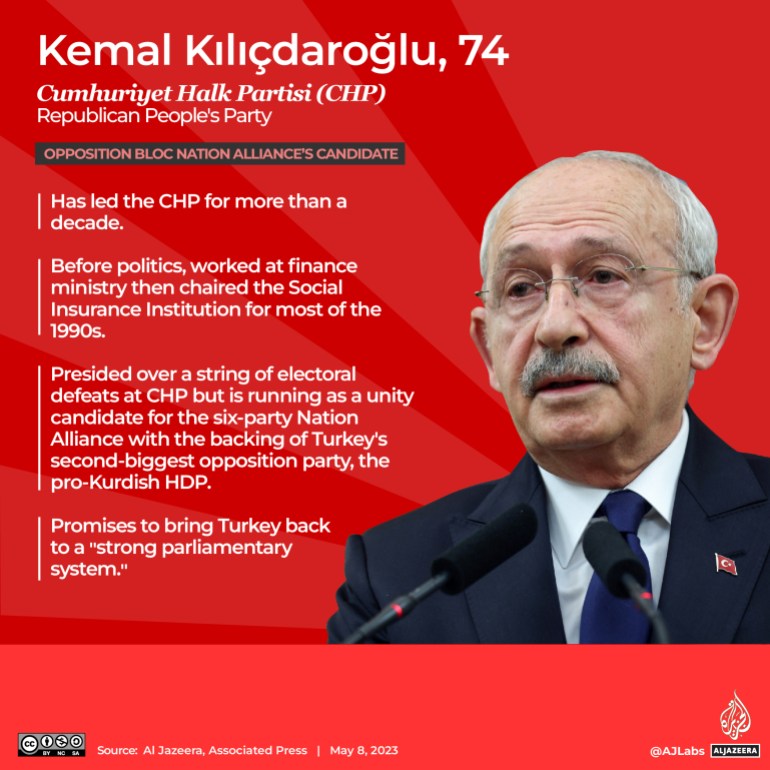

But a possible new successor is on the rise, with emboldened opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu from the Republican People’s Party, or CHP currently holding an edge in opinion polls.

Kilicdaroglu, a social democratic politician also backed by five smaller parties in an alliance against Erdogan, has promised to overturn the president’s legacy.

Sinan Ogan from the ATA alliance is also vying for the top spot. A former candidate, Muharrem Ince from the Homeland Party dropped out of the race just three days before the election.

So, Turkey may enter a post-Erdogan era after Sunday’s presidential and parliamentary elections, and that could mean foreign policy changes.

Personality-driven to predictability?

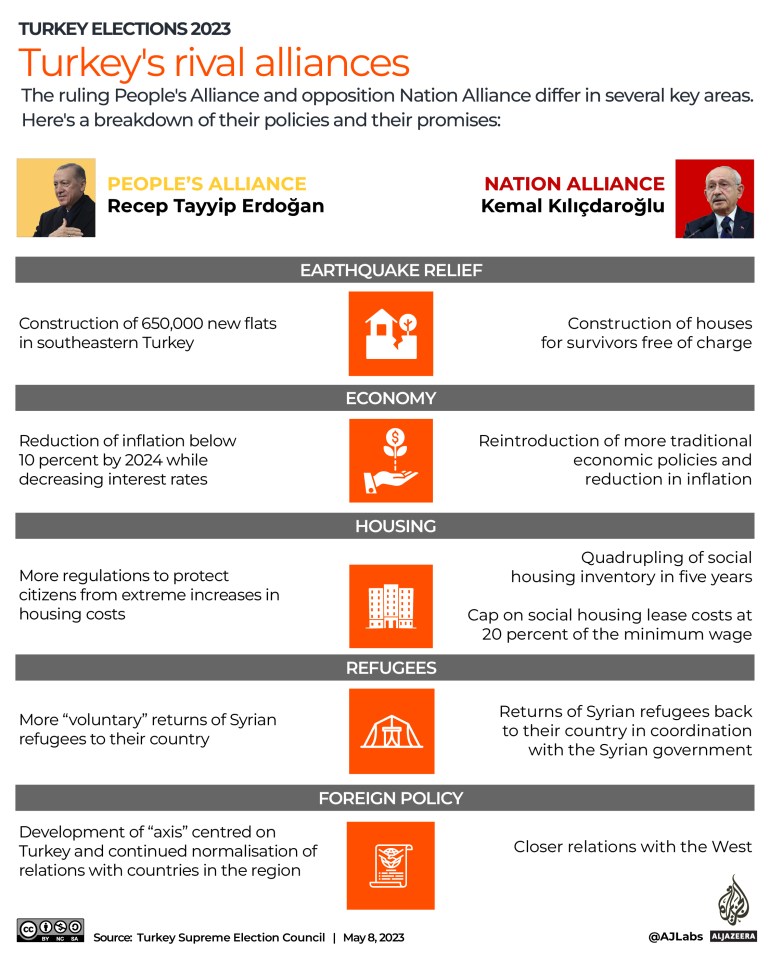

If Erdogan’s reign was about pomp and personality, the opposition’s – especially under Kilicdaroglu – may be more muted and predictable.

“The style of foreign policymaking will change and that’s more important than issue-based changes because currently foreign policy is conducted entirely [in] a personalised manner,” Salim Cevik, a researcher at Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik’s Center for Applied Turkey Studies in Berlin, Germany, told Al Jazeera.

Under Erdogan, foreign ministers and diplomats have largely been excluded from decision-making, with personal relations between the president and foreign leaders waging a far greater role, Cevik added.

“Turkey will be much more predictable because it will be more institutionalised,” the researcher said.

Sami Hamdi, the managing director at International Interest, a political risk firm focusing on the Middle East, said that Erdogan’s policies are also aimed at increasing Turkey’s soft power, particularly in the Muslim world, a continuation of the legacy of the Ottoman Empire, which ruled vast swaths of the Middle East, North Africa and the Balkans for centuries.

“Erdogan’s assertive nature has irked the major powers who are more accustomed to Turkey’s historical role as a supporting actor,” Hamdi told Al Jazeera.

“At the same time, Turkey’s rapidly expanding influence is rooted in Erdogan’s ability to capitalise on Islamic soft power via his ‘Muslim’ rhetoric, enabling him to advance rapidly both politically and economically into [multiple regions],” he added.

Middle East ties from military interventions to normalisation

Erdogan’s foreign policy has seen the leader flex his military prowess across the Middle East through interventions in Iraq, Libya, Syria and even beyond, in Azerbaijan.

In Iraq and Syria, Turkey’s military actions have focused on stamping out threats it saw as linked to the banned Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which has been waging a deadly fight against the Turkish state that has killed tens of thousands since the 1980s.

As such, Ankara has spent decades fighting predominantly Kurdish forces in northern Iraq, and controls several areas along its borders with Syria, in order to crush the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the US-backed forces Ankara considers an offshoot of the PKK.

In Libya, Turkey intervened to support the United Nations-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli against eastern-based forces and in 2020, backed Azerbaijan in a war with Armenia over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region.

On paper at least, the CHP has said it will reverse course and take on a non-interventionist role, according to the party’s platform.

“We will respect the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of the countries in the Middle East, will not interfere in their internal affairs, and will not ‘take sides’ in the problems between them but ‘facilitate solutions,’” the platform read.

Sinan Ulgen, a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe in Brussels, Belgium, said Turkey’s non-interference in other countries’ domestic affairs had been a pre-Erdogan principle, but the opposition pulling out of Syria and Libya would still be conditional on Ankara’s interests being protected there.

“That would be conditional on an overall agreement with [Damascus and Tripoli] that would protect its interests,” Ulgen told Al Jazeera.

Cevik was less inclined to agree that a pull-out from the two places would take place under an opposition government so quickly, but Turkey will head towards a less militarily-aggressive era regardless, due to economic restraints.

“[The] Turkish economy is bad and became even worse after the earthquake so the resources are limited,” said Cevik.

He pointed to Turkey’s recent more diplomatic and muted responses to issues that in the past would have provoked Erdogan to a greater extent, such as Israeli attacks on Gaza, or the crackdown on the opposition in Tunisia.

Erdogan has already begun a new course by normalising ties with Arab states, a process that would likely continue under the opposition.

Turkey’s ties with Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates soured after Ankara supported the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and elsewhere during the 2011 Arab uprisings.

Meanwhile, Ankara’s closer ties with Riyadh’s rival, Tehran, and the Saudi killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul exacerbated those rifts.

“The motivation is to normalise the ties that have been tarnished over the past decade as a result of Turkey’s … confrontational, or interventionist, policies in the region,” said Cevik.

But Turkey may see a dip in popularity in the region as it takes a step back from Middle Eastern affairs, the researcher said.

That will especially be true under Kilicdaroglu, said Hamdi, as he was seen as the candidate committed to “divorcing” Turkey from the Muslim world, while Erdogan has been seen as one committed to restoring Turkey to the Muslim world and re-defining Turkish identity with an “Islamic stroke”.

“The image of Turkey in the region will change dramatically if Kilicdaroglu wins,” said Hamdi.

Ties with the West – from frosty to friendly?

Perhaps where change in foreign policy is most likely to occur with a change of government is in Turkey’s relations with the West.

“According to the policy platform of the opposition, the new Turkish foreign policy will seek to reassert Turkey’s Western vocation,” said Ulgen.

An opposition-led government would seek to improve Turkey’s relations with its traditional partners in the West, namely the European Union and the United States, but the “outcome of this will also depend on how Washington and Brussels react to the prospect of political change in Turkey,” he added.

The West may welcome Kilicdarolgu not due to its own interests, but rather because he is perceived as someone less assertive in imposing Turkish interests, said Hamdi.

“Much of Erdogan’s use of force has been the result of genuine fears in Ankara that something bad is about to happen to Turkish interests, and that his allies have not taken those fears seriously,” he explained.

According to Cevik, a general pro-Western outlook in foreign policy has been the default for Turkey in even the AK Party’s first decade in power, after 2002.

Tensions have always existed, but even when Turkey was under a heavy American arms embargo in the 1970s, “these tensions didn’t amount to questioning Turkey’s membership in the wider Western geopolitical system,” he said.

“Today, this is questioned,” Cevik emphasised.

Others have argued that it is the West that has pushed Turkey away.

While most parties in Turkey prefer closer ties and integration with Europe, Europe does not consider Turkey part of its fold, and France, in particular, has been vocal about this, said Hamdi.

“As a result, Erdogan has shifted his priorities and placed greater importance on the Islamic world, where Turkey has been able develop new alliances, new ties, and rapidly expand its influence and soft power to become a major – and more independent – player in the region,” said Hamdi.

Erdogan was relatively friendly with former US President Donald Trump, but relations with current US President Joe Biden have been more frosty.

Washington removed Ankara from its F-35 joint strike fighter programme in 2019 after Turkey bought S-400 air defence systems from Russia, systems incompatible with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) ones.

The CHP’s platform promised to return Turkey to the F-35 programme, but does not state whether Turkey would return the Russian systems.

Turkey has also been wary of the US’s support for the YPG in Syria, officially through the Syrian Democratic Forces, of which it is the leading part.

Still, Turkey’s support for Ukraine and its reversal on its opposition to Finland joining NATO – while remaining uncertain over Sweden – have spurred Washington to sell Ankara F-16 jets and other military equipment in the interest of NATO unity.

Under a potential new government, many of these issues may still stand but “there will be a willingness by the new Turkish government to address these issues more constructively”, said Ulgen.

Equally, it will also “depend on how much flexibility the US side will be willing to demonstrate to resolve these issues”, he added.

Some thorny issues with the EU may also persist in a post-Erdogan era, namely the Cyprus dispute and Turkey’s feud over maritime rights with Greece, the analysts said.

However, a notable difference in the CHP’s platform was that it would concede to the EU accession process demand that Turkey release some Turkish political prisoners.

Despite soured relations over these matters during Erdogan’s rule, the EU has remained Turkey’s principal trading partner and source of foreign investment.

While the Turkish opposition has remained committed to the EU accession track, its ties with the regional bloc are not limited to that, said Ulgen. A new government will pursue everything from visa liberalisation, to deeper cooperation in the areas of trade, climate, digital and beyond, he added.

Ties with non-Western powers, China and Russia

Although Turkey may warm up to the West under the opposition, its ties to Russia and China would remain intact.

But the opposition, Ulgen said, will seek to balance its allies more strategically than Erdogan did.

Beyond Su-57 warplanes and ice cream cones, Erdogan and Putin have no doubt held close ties, with Turkey heavily reliant on Russian energy imports.

Even still, the two have backed opposing sides in Libya, Syria, and the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict. Turkey also condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, supplying the latter with drones. It still, however, opposed Western sanctions on Russia, a balancing act that the opposition will likely continue.

Similarly, Turkey has allied with China for years, in 2015 joining its infrastructure-financing Belt and Road Initiative. However, the persecution of the Uighur people – who are Turkic and speak a language similar to Turkish – in China has been an under-the-rug issue between the two allies, with Erdogan accusing China of “genocide” in 2009, but not publicly pressing the issue since.

“China’s policies on [the Uighur] front constitute an impediment to a vast improvement of the relationship,” said Ulgen.

The key difference, then, between a third Erdogan term and a post-Erdogan era, would likely be that the incumbent candidate would continue to foment these relations in a continued push away from the West, he said.

“Under Erdogan, Turkish foreign policy will be more influenced by a drive to obtain a strategic autonomy from the West, which opens up more space to countries like Russia and China,” the analyst said.

Ties with Africa

Turkey’s Africa policy has largely been dictated by trade and investment, said Cevik, and will continue irrespective of who wins the election, as it is considered a success.

“Most recently, drones sales and arms cooperation became an important dimension of Turkish presence in Africa,” he said. “I am expecting that to continue but the new government may be more selective and less eager in selling drones”.

On the cultural front, however, Turkish NGOs carrying out religious activities on the continent may not have as much support from an incoming CHP-led government.

As a result, Turkey’s cultural influence in Africa will continue to some extent but may slow down under the opposition, the researcher said.

Hamdi agreed that a government under Kilicdaroglu would not be able to be as influential in Africa as during Erdogan’s reign.

“Kilicdaroglu does not evoke anything of the resonance that Erdogan does, and Turkey’s economic and cultural influence is likely to be greatly hampered if he becomes president,” he said.

Ulgen, on the other hand, believed that a new government may collaborate with its Western partners to contain the influence of China on the continent, in order to advance Turkish interests there.

A new international position?

Two decades of rule fashioned by Erdogan have changed Turkey in multiple ways, and its place in the world, both positively and negatively, depending on who you ask.

A third presidential win for Erdogan would be a vindication of his policies since, said Ulgen, despite his dipping popularity.

But the opposition – while still continuing elements of Erdogan’s foreign policies – would seek to reposition Turkey internationally by balancing its relations on the world stage, the analysts said.

“[Turkey will] continue to have solid relations with its neighbours and the non-West powers, Russia, China,” said Ulgen.

“However, this would not come to the detriment of Turkey’s geo-strategic alignment as a partner of the Western community of nations,” he added.