The looming question of Kurdish independence in Iraq

A Kurdish vote on independence in northern Iraq could be felt across the region at large.

With the upsurge of sectarian violence and political chaos in the Middle East, one of the region’s most protracted conflicts has been brought to the fore: the Kurdish question.

Earlier this month, Masoud Barzani, the president of the Iraqi Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG), announced plans to hold a referendum on independence for the northern Kurdistan region.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTurkey hits 71 targets in Iraq, Syria in retaliation for soldiers’ deaths

Turkey says bombers came from Syria, threatens more cross-border strikes

‘Iraqis love life’: In conversation with Ala Talabani

While a “Yes” vote, which is widely expected to be the result, would not lead to an automatic declaration of independence, it would to give Iraqi Kurds, who make up about 20 percent of the population, more leverage in talks on self-determination with the central government.

|

|

Politically, the KRG already functions as an independent nation-state with its own parliament, armed forces (known as the Peshmerga) and foreign policy within a federation with the rest of Iraq. But economically, the KRG is still dependent on the central government as a result of a revenue-sharing system for oil wealth.

The regional government also heavily relies on its two main trade partners Turkey and Iran, both of which have come out against the referendum for fear the vote will further embolden their own Kurdish populations.

“We think this will represent a terrible mistake,” said the Turkish foreign ministry in a statement. “The maintenance of Iraq’s territorial integrity and political unit is one of the fundamental principles of Turkey’s Iraq policy.”

But in a country that is already rife with sectarian violence, the move is likely to strain already fragile relations between the regional capital Erbil and Baghdad, and risks sparking intra-Kurdish clashes that could spill over into neighbouring countries.

Baghdad has already rejected the referendum call.

“No party can, on its own, decide the fate of Iraq, in isolation from the other parties,” Saad al-Haddithi, Iraqi government spokesman, said earlier this month in a statement.

“Iraq is constitutionally a democratic, federal country with full sovereignty…Any measure from any side in Iraq should be based on the constitution.”

Iraqi Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi said in April that while he respected the Kurdish right to vote on independence, he did not think the timing was right for the move.

OPINION: Iraqi Kurdistan – Playing the independence game

The vote, set for September 25, will take place in the three governorates that make up the autonomous Kurdish region (Erbil, Dohok, and Suleimaniah), as well as other disputed areas that are claimed by both Kurdish Iraq and Baghdad: Makhmour in the north, Sinjar in the northwest and Khanaqin in the east, and most importantly, the oil-rich province of Kirkuk.

The city of Kirkuk, which sits atop an estimated three percent of global proven oil reserves, is home to a large mix of religious and ethnics groups, including Kurds, Arabs, Turkmen and Christians, making it the most important disputed area and a constant source of contention.

Iraq’s Kurds have likened Kirkuk to their own “Jerusalem”.

Last April, attempts to raise the KRG flag on top of public buildings in the city sparked backlash and accusations of “sedition” from the central government.

Iraqi Kurds had previously accused Baghdad of manipulating the demographic makeup of the city by forcefully pushing Kurds out and settling in Arab families in their place as part of the “Arabisation” policies of Saddam Hussein.

In addition to systematic discrimination policies, Hussein led a bloody campaign against Iraqi Kurds, known as the “Anfal Campaigns” of 1987 to 1989, during which thousands of villages were reportedly burned and destroyed. Human Rights Watch put the total number of deaths and disappearances during these campaigns between 50,000 and 100,000 people.

During the last days of the eight-year war, the Baathist government carried out a chemical attack in the Kurdish town of Halabja, immediately killing up to 5,000 people.

Two years after the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, which brought an end to Hussein’s Baathist regime, a new federal constitution was drafted that approved and listed the Kirkuk province as one of the disputed territories whose legal fate would depend on a referendum.

Iraqi Kurds have since sought to annex the disputed territories by employing two provisions of the new constitution: Article 140, which mandates the reversal of Hussein’s Arabisation policies; and Article 119, which allows governorates to become or join an existing region by a referendum.

The government’s failure to implement the provisions before a December 2007 deadline cast doubt on the viability of KRG’s soft approach and led to renewed mistrust between Erbil and Baghdad.

The dispute over the Kirkuk province, aside from the Kurds’ claim to the land, is further hindered by a constitutional ambiguity. The federal constitution stipulates that the management of oil and gas extracted from “present fields” is the responsibility of both the federal and regional governments, and mandates that oil revenues are to be distributed equally across the country. But it fails to stipulate whether the largely untapped oil reserves in KGR territory are considered within the “present fields”.

|

|

Aided by this legal loophole, the KRG has invited a number of international oil companies (IOCs) to develop its untapped resources and has kept all the revenue for itself, drawing the ire of the central government.

Kurdish Peshmerga forces have been key in reversing gains made by the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also known as ISIS) since it swept across the country in 2014. In doing so, the US-backed Kurdish forces have steadily expanded KRG-controlled territory, unilaterally expanding into “contested areas”, many of which were victim of Saddam Hussein’s “Arabisation” policies.

With the battle for Mosul nearing an end, the KRG will be in the position to use its control over vast new swaths of territory in its negotiations with Baghdad.

Further complicating matters is the KRG’s rivalry with the Sinjar Resistance Units (YBS), a Yazidi armed group affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) that has been waging a bloody battle for greater autonomy in Turkey since 1984.

The Peshmerga forces – Ankara’s main allies in Iraq – have repeatedly clashed with the YBS, who in turn have warned the KRG of attempting to assert its control in Sinjar, another disputed area.

And as PMU units push further into Sinjar in an effort to clear ISIL from the Iraq-Syria border as part of the ongoing efforts to take Mosul, their collaboration with PKK-allied YBS fighters have prompted fears of Turkish military intervention.

In Pictures: Kurds in Iraq ring in the new year

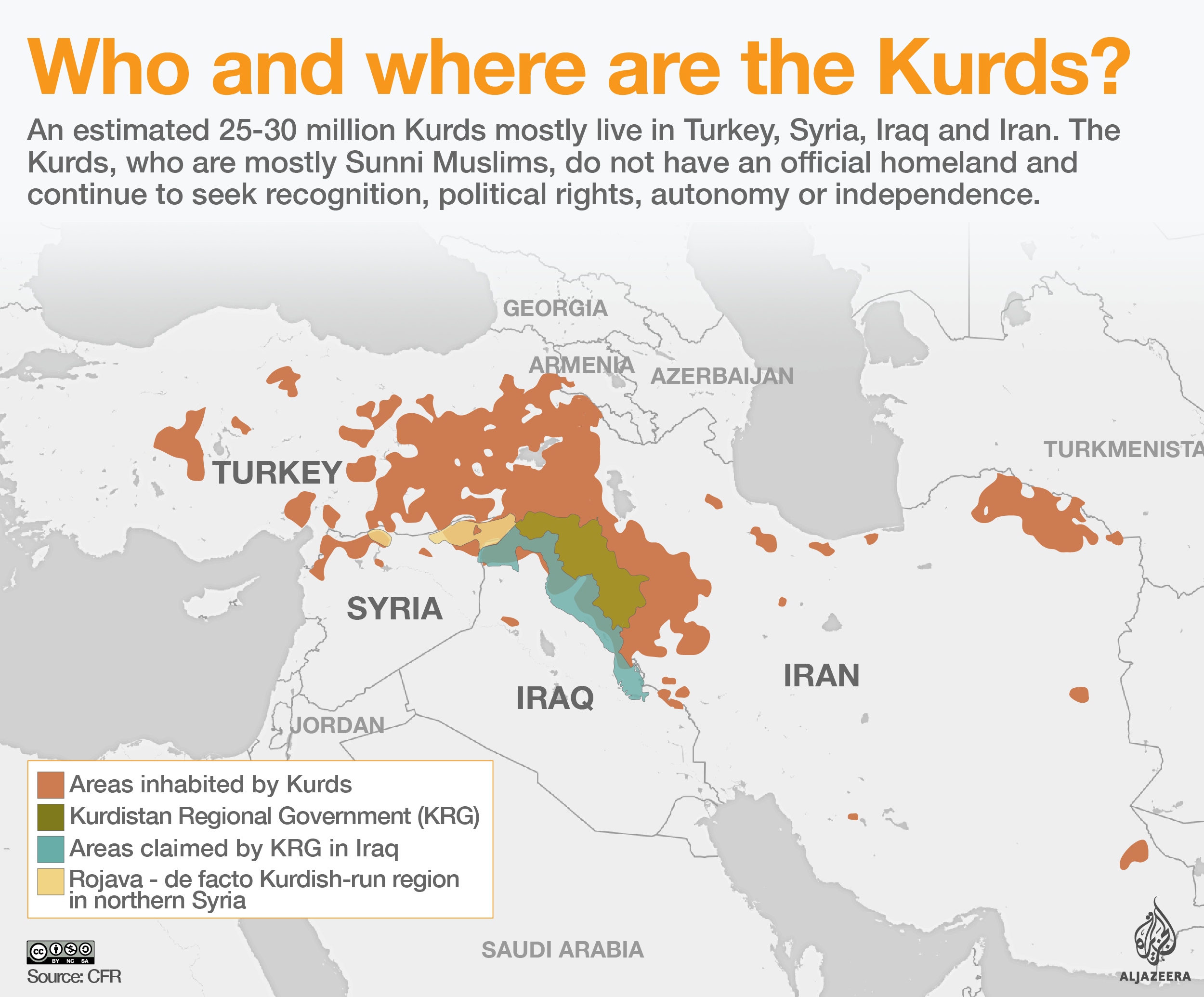

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in early 20th century, the Kurds, a distinct people with their own language and culture, found themselves scattered across four regions: Southeastern Turkey, parts of Iran, northeastern Syria and northern Iraq – areas they regarded as their ancestral homeland ever since.

Alarmed by their aspirations for cultural and political autonomy, and in some cases, pursuits for independence, the successive governments of Turkey, Iran, Syria and Iraq have systematically subjugated their Kurdish populations through decades of assimilation, repression and containment policies.

In Syria, some 120,000 Syrian Kurds were left without citizenship and thousands of others were forced to flee to other Kurdish regions as a result of a racially motivated census that dates back to 1962.

Today, Syrian Kurds, who make up the biggest ethnic minority group in the country with a population of about two million, are displaying similar aspirations for autonomy, although not independence per se, to those of the Kurds in Iraq.

Aided by the security vacuum caused by the Syrian civil war, the Kurdish-led Democratic Union Party (PYD) and allied groups declared a form of “federal democratic system” in the northern part of the country, dubbing the territories under its control “Rojava” (or Western Kurdistan).

The PYD and its armed wing, the People’s Protection Units (YPG) – a key US ally in the fight against ISIS in Syria – have been advocating for a form of democratic federalism in Syria

With the war in Syria now well into its sixth year, and with Iraqi Kurds taking a step closer toward independence, Syrian Kurds could reconsider their self-determination aspirations and seek independence, adding a complicated layer to a region already entangled in a complex web of conflicts.