Why is Guantanamo Bay prison still open 20 years after 9/11?

The fate of 39 detainees who are still being held rests with US President Joe Biden, who has pledged to close the prison.

Moath al-Alwi was captured by Pakistani forces near the Afghanistan border in December 2001 and given over to the United States military.

A Yemeni national, al-Alwi has said he was fleeing for safety, not a fighter, when he was abducted and sold to the US military, which in January 2002 transported him across the world to a tropical prison camp at the US Navy base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsGuantanamo detainee due in military court over Indonesia bombings

Biden administration transfers first detainee from Guantanamo

US approves release of oldest prisoner at Guantanamo: Lawyer

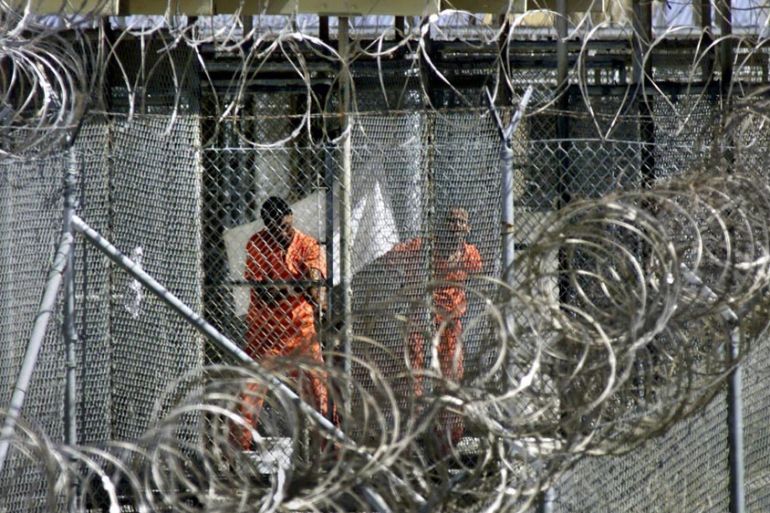

In the nearly 20 years since, the notorious military prison at Guantanamo has become a symbol of US human rights abuses. Many detainees – mostly Muslim men – were tortured or held for years and even decades without charges, trials or basic legal rights.

One of a few dozen remaining detainees at Guantanamo Bay, al-Alwi has never been charged with any crime, and yet remains in prison. The US Supreme Court in 2019 turned down his petition without comment.

With the departure of American troops from Afghanistan, rights advocates see an opportunity for President Joe Biden to fulfill his 2020 political pledge to close the prison. Others say the takeover of Afghanistan by the Taliban, some of whose new leaders are former Guantanamo prisoners, creates a new obstacle.

Why is the US military prison at Guantanamo Bay still open?

“The fact that the prison remains open 20 years later is because of US partisan politics and, unfortunately, the prisoners there are hostages to that politics,” said Ramzi Kassem, a professor at the City University of New York School of Law who represents al-Alwi and another detainee still being held without charge at Guantanamo.

There was broad public consensus in the US at the end of the presidency of George W Bush in 2008 that Guantanamo should be closed.

President Barack Obama declared he would close the prison, but drew sharp criticism from Republicans and failed to fulfil his promises after the US Congress moved beginning in 2011 to impose limits on the transfer of detainees.

Taking the White House in 2016, President Donald Trump opposed releases from Guantanamo and said he would “load it up with bad dudes”. In his four years in office, Trump released only one person.

“It’s a bipartisan lack of political will to close Guantanamo and do what would be sound from a policy standpoint. Administrations of both parties have failed to do what’s necessary,” Kassem told Al Jazeera.

Who is still being held at Guantanamo?

A relatively small number of 39 men are still being held at Guantanamo. They include Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the al-Qaeda attacks on the US on September 11, and four co-conspirators who face trial by military commissions.

Ten of the detainees do not face charges and have been approved by US agencies for release but are still being held. Among them is Saifullah Paracha, a Pakistani man who at age 74 is the oldest detainee at Guantanamo and who has never been charged with a crime.

Ten men face still face military commission proceedings. One is nearing the end of a military sentence and is due to be released in February. Others are being held indefinitely without trial.

Who has been released from Guantanamo?

The Bush administration transferred about 540 detainees out of Guantanamo by the end of 2008, and the Obama administration transferred nearly 200 out of the facility by the beginning of 2017.

Among the challenges US authorities face in transferring detainees out of Guantanamo is obtaining agreements guaranteeing humane treatment from their home countries, or getting a third country to agree to resettle them and prevent their return to hostilities against the US.

Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, Slovakia and Albania have been among the largest recipients of nationals from other countries.

In 2014, five Taliban prisoners were transferred to Qatar in exchange for the release of American soldier Bowe Bergdahl, who was held captive for five years in Afghanistan and Pakistan after deserting the US Army. Four of those five are now members of the new Taliban government in Afghanistan.

Two men have been released since Obama left office in January 2017. Both were returned to their home countries.

After more than 15 years at Guantanamo, Ahmed al-Darbi was returned to Saudi Arabia in 2018 to continue serving a prison sentence for a 2002 bomb attack on an oil tanker off the coast of Yemen.

On July 19, the Biden administration released its first detainee, Abdul Latif Nasser, a Moroccan, four years after he had been cleared for transfer in 2016. Held for 19 years, Nasser was never charged with any crime.

What are the military commissions at Guantanamo?

The military commissions are tribunals organised outside the framework of US and international law by the US Department of Defense to bring charges against detainees at Guantanamo.

US constitutional protections of due process do not apply, allowing the government to maintain secret evidence derived from torture and to hold detainees indefinitely.

“The commissions were created really to evade the normal rules that would constrain the operation of a regular civilian or military court, and specifically prohibitions on the use of tainted evidence,” said Kassem.

Detainees are required to use the lawyers assigned to them. They are not allowed to see all the evidence against them. Only two-thirds of a jury is required to convict, and even in cases of acquittal, release is not guaranteed.

How were detainees tortured by the US?

Many of the detainees at Guantanamo were first held in black sites by the CIA or elsewhere by the US military and were tortured before being transferred to Guantanamo.

Those records are largely still secret and lawyers who represent detainees are required to enter non-disclosure agreements that prevent them from publicly describing the torture suffered by their clients.

In June, a military judge for the first time publicly agreed to allow information obtained through torture to be used in a military case against Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, a Saudi accused of planning the bomb attack on the USS Cole in 2000 that killed 17 US Navy sailors.

“The military commissions from their inception were set up to accommodate the fact that men, especially the former CIA detainees, had been tortured and to cloak those abuses in secrecy,” said Hina Shamsi, director of the national security project at the American Civil Liberties Union.

The US government has acknowledged torture took place in a number of cases, among them that of Abu Zubaydah, a Palestinian man captured by the US in Pakistan and tortured for years in a series of secret CIA prisons, as detailed in a US Senate report.

Another is Mohammed al-Qahtani, a Saudi whose military charges were dismissed because he had been tortured at Guantanamo but who remains imprisoned despite mental illness.

What steps can Biden take to close Guantanamo Bay?

Human rights advocates and lawyers for detainees say the Biden administration will be under increasing pressure to bring Guantanamo to a close.

“It’s going to be unsustainable for the Biden administration to make the argument that US involvement in Afghanistan has ended but it continues to have authority to detain men indefinitely at Guantanamo,” said J Wells Dixon, a senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York.

“You can’t have it both ways,” said Dixon, who has represented a number of Guantanamo prisoners including Majid Shoukat Khan, a Pakistani who endured CIA torture and subsequently pleaded guilty to being a courier for al-Qaeda.

The White House announced in February that it is conducting an internal review of how to close Guantanamo. One major step, advocates say, would be to dispense with the military tribunals and allow the US Department of Justice to attempt to reach plea deals with the 9/11 suspects and others accused of crimes.

Biden can ask Congress to repeal its prohibitions on Guantanamo detainees entering the US for purposes of serving prison terms.

Biden is considering naming a special envoy at the US Department of State for closing Guantanamo, a position created by Obama but eliminated during the Trump administration.