Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring in northern Syria: One month on

Al Jazeera looks at last month’s developments that followed Ankara’s offensive on Kurdish fighters in northern Syria.

Turkey launched a military operation across its border in northeast Syria a month ago, securing control of a large swathe of territory in the region.

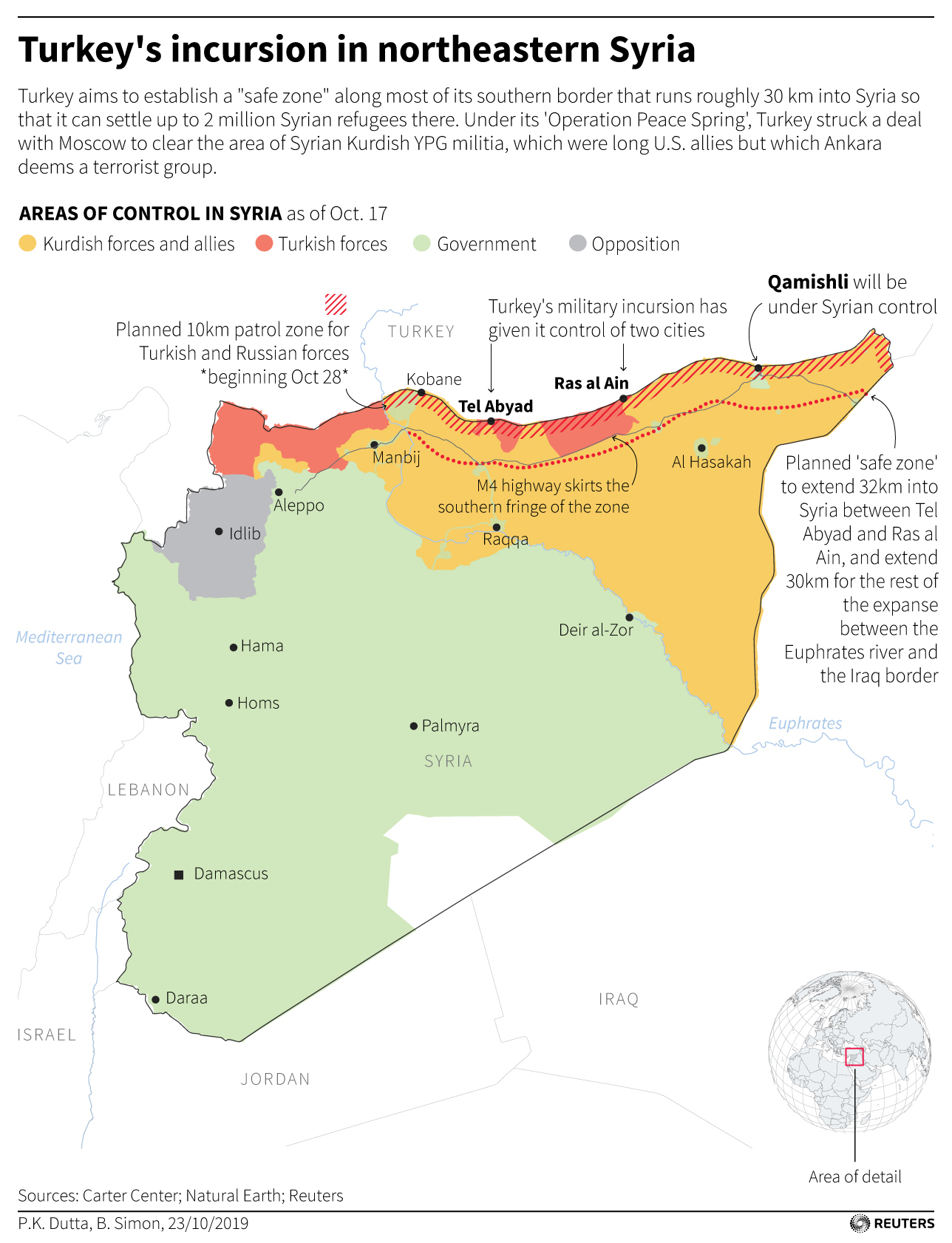

Turkey said the offensive, which began on October 9, was aimed at removing Kurdish fighters, considered terrorists by Ankara, from the border region and establishing a “safe zone” to resettle some of the refugees in the country.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAslan, a little Syrian boy’s journey to hear again

Student, volunteer, shopowner: NW Syria’s Shaima defies limitations

World Food Programme to end general assistance in northwest Syria

Ankara had been in talks with the United States to create a jointly controlled “safe zone” for months before the operation and blamed Washington for stalling the initiative, which it said was necessary for Turkey’s security.

Days before the offensive, the US in a surprise move withdrew its forces from the Kurdish-controlled region that would be targeted by the operation, opening the door for Turkey to carry out the offensive.

The operation received harsh international criticism from Turkey’s NATO allies as the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) had been a loyal ally of the US-led coalition fighting against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS) and played a key role in defeating the group in Syria.

The SDF is led by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which Ankara calls an extension of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), an outlawed armed group that Turkey considers a terrorist organisation.

The PKK has been fighting the Turkish state for decades, initially in an attempt to secure an independent Kurdish state. More recently, it has altered its goal to more autonomy for Kurdish-majority areas in Turkey. Since the conflict began in the 1980s, more than 40,000 people have died.

On the day the operation began, US President Donald Trump sent his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdogan an unconventional letter, advising him not to be “a tough guy” and to negotiate with the SDF instead of carrying out a military attack.

In response, Turkish presidential sources said Erdogan thoroughly rejected the letter and put it in the bin.

Days later, Trump proceeded to impose limited sanctions on Turkey over the military action, but kept diplomatic channels open with Ankara.

Turkey’s European allies expressed strong condemnation of the Turkish offensive with French President Emanuel Macron calling it “madness” and German Chancellor Angela Merkel calling it “an invasion”. Both countries suspended arms sales to Turkey, along with other European Union member states.

As the operation progressed, the Syrian government and allied Russian forces moved into the Kurdish-controlled areas where Turkish and aligned forces had not reached, on the invitation of the SDF to fend off a wider Turkish assault.

Pence’s key visit

The fighting between the Turkish and allied forces and the SDF continued for some 10 days until October 18, when Mike Pence, the US vice president, announced that Washington and Ankara had agreed on a ceasefire over Turkey’s offensive.

The deal, which was reached after a snap meeting between Pence and Erdogan in Ankara, gave the SDF 120 hours to pull its forces 30km back from a 120km long strip along the Turkey-Syria border, the planned Turkey-controlled “safe zone” area between the towns of Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain.

This area was smaller than what Turkey had hoped for before the operation; a “safe zone” along the whole Syrian-Turkish border, including the territory it controls in northwest Syria through previous cross-border operations.

Shortly after the deal was announced, the White House removed the sanctions on Turkey, although the House of Representatives pursued new sanctions later in the month which are still in the legislative pipeline.

The US-brokered ceasefire largely held with only sporadic fighting reported through the five days.

Hours before the end of the truce, a second ceasefire agreement was reached between Turkey and Russia to give the Kurdish fighters another 150 hours to complete their withdrawal from the planned “safe zone”, after which Ankara and Moscow would run joint patrols around the area.

According to the agreement, the SDF would also pull back from now Syrian-controlled key towns close to the border, such as Manbij and Kobane.

The joint patrols aimed to prevent potential clashes between Turkish and allied rebel forces, and the Syrian government forces that moved to Kurdish-controlled areas outside the operation – or the “safe zone” – area.

Sporadic clashes were also reported during the Russia-brokered truce, before Moscow announced that the SDF withdrawal was concluded on October 29. The first joint Russian-Turkish army patrols started on November 1.

‘Turkey achieved goals’

Sinan Ulgen, a political analyst and former Turkish diplomat, said that Turkey achieved its primary goals through the operation, although it wanted to establish a larger “safe zone” before the move.

According to Ulgen, Turkey’s priority has not been about who controlled the Syrian side of the border in this process, but it demanded the areas close to the border be freed of threats against its security.

“And this has for the most part been achieved through the deal made with Russia as well as the US as they include withdrawal of the YPG forces from border areas even if they are in control of the Syrian government,” he said.

Mensur Akgun, a professor of international relations in Istanbul, agreed that Ankara established its goals through the offensive, without losing much resources.

Akgun said that Turkey’s operation sparked a diplomatic drive among the actors in Syria, which led to the current outcome.

“Through this diplomatic traffic that began as a result of the operation, Ankara achieved most of what it wanted on the ground through a short period of clashes and low level of casualties,” he said.

Although Turkey presented the outcome of the operation as a diplomatic and military victory, the country came under fire over alleged human rights violations during the operation, particularly because of the actions of allied Syrian rebel forces.

A recent report in the New York Times revealed an internal memo from a top diplomat in Syria who accused Turkish-backed fighters of committing “war crimes and ethnic cleansing”, claiming that they killed prisoners during the operation, among other crimes.

The October 31 memo by William V Roebuck, the deputy special envoy to the global coalition to defeat ISIL, criticised the Trump administration for not doing enough to stop Turkey’s operation.

Human rights groups, such as Amnesty International, said last month there was evidence that activities of Syrian rebel fighters amount to “war crimes”, and that they killed and injured civilians.

|

|

The atmosphere on the ground has been relatively calm since the end of the operation, apart from a recent blast in the now Turkish-controlled town of Tal Abyad that reportedly killed several people. Ankara blamed the Kurdish fighters for the incident.

Ankara recently said that the YPG forces did not withdraw from all the regions promised in the Russia-Turkey deal, but this did not lead to clashes on the ground.

Turkey has also announced its intention to send back ISIL prisoners in the new areas it controls in Syria to their home countries.

Erdogan also presented a plan to the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres for resettling up to two million Syrian refugees in the areas it controls now.

Operation Peace Spring was Turkey’s third military operation in three years targeting Syrian-Kurdish fighters, after Operation Euphrates Shield in 2016 and Operation Olive Branch in 2018.

Follow Umut Uras on Twitter: @Um_Uras