Theresa May triggers Brexit Article 50

Article 50 letter hand delivered to European Union by British ambassador, initiating two-year countdown to EU exit.

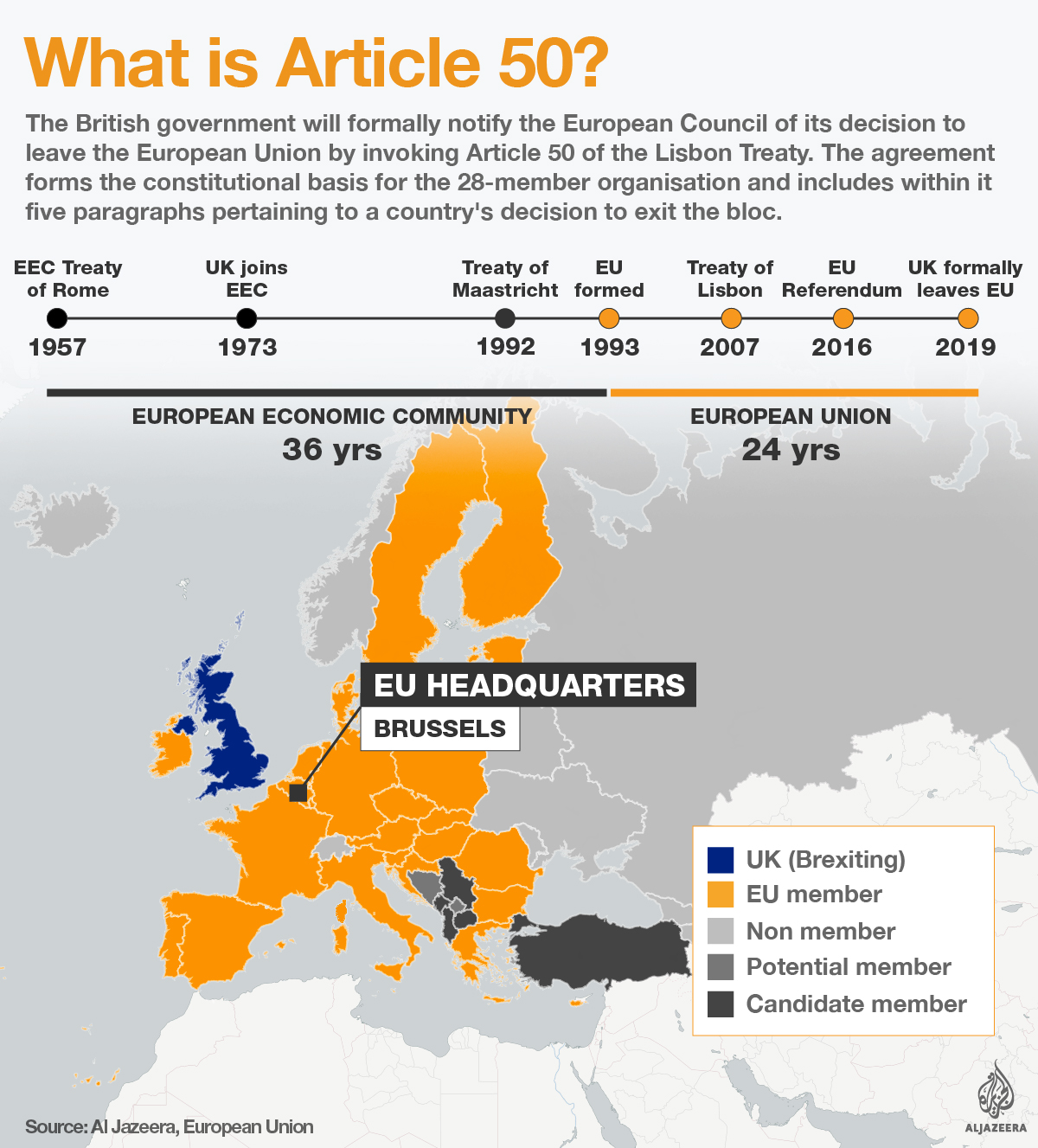

UK Prime Minister Theresa May has triggered the formal two-year process of negotiations that will lead to Britain leaving the European Union after 44 years in a process popularly known as Brexit.

A letter invoking Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty and officially notifying the EU of Britain’s decision to withdraw from the bloc was hand-delivered to European Council President Donald Tusk in Brussels by British Ambassador to the EU Tim Barrow on Wednesday.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhy are British farmers pleading for a universal basic income?

Northern Ireland agreement could end deadlock, restore government

Forced to become British: How Brexit created a new European diaspora

The loss of a major member is destabilising for the EU, which is battling to contain a tide of nationalist and populist sentiment and faces unprecedented antipathy from the new US administration.

It is even more tumultuous for Britain.

For all the UK government’s confident talk of forging a close and friendly new relationship with its neighbours, it cannot be sure what its future relationship with the bloc will look like – whether businesses will freely be able to trade, students to study abroad, or pensioners to retire with ease in other EU states.

Those things have become part of life since the UK joined what was called the European Economic Community in 1973.

|

|

In a speech to parliament designed to coincide with the letter’s delivery, May urged the country to come together as it embarks on a “momentous journey”.

“We are one great union of people and nations with a proud history and a bright future. And now that the decision has been made to leave the EU, it is time to come together,” she said.

May told MPs she wanted to represent “every person in the UK”, including EU nationals, in negotiations.

The prime minister acknowledged that there would be “consequences” to leaving, and she said the UK accepts it cannot “cherry pick”, and stay in the single market without accepting free movement.

EU Council President Donald Tusk said there was “no reason to pretend this is a happy day”.

“We already miss you,” he said, adding there was “nothing to win” and that now the Brexit process was about damage control.

Britain voted to leave the EU last June, after a campaign that divided the country. In a close result, 52 percent voted for Brexit, while 48 percent wanted to stay in the EU.

Scotland and Northern Ireland voted overwhelmingly to remain in the EU, while England and Wales, with a much larger combined population, voted to leave.

Al Jazeera’s Barnaby Phillips, reporting from London, said May’s speech attempted to strike a delicate balancing act.

“Throughout the speech Theresa May is talking to two audiences simultaneously. She’s talking to the audience across Europe, but she’s also talking to a wide range of opinion in the country.

“She’s trying to assuage the disappointment of the ‘remainers’, but she’s also trying to rein in some of the hardline Eurosceptic ‘leavers’ – many of whom belong to her own party … [and] a conservative-dominated press in this country who are much more gung-ho about the terms of Brexit,” Phillips said.

OPINION: Brexit is still happening, just not the way May hoped

May has promised to take Britain out of the EU single market but negotiate a deal that keeps close trade relations with Europe, as she builds “a strong, self-governing global Britain” with control over its own borders and laws.

Brexit Secretary David Davis said Britain was “on the threshold of the most important negotiation” for Britain “for a generation”.

Challenges ahead

The British parliament backed May’s Article 50 plan earlier this month, after six weeks of debate.

The EU is expected to issue a first response to Britain on Friday, followed by a summit of EU leaders on April 29 to adopt their own guidelines – meaning it could be weeks before formal talks start.

Their priority is settling Britain’s outstanding obligations, estimated between 55bn and 60bn euros [$59bn and $65bn] – an early battle that could set the tone for the rest of the negotiations.

Both sides have said they are keen to resolve the status of more than three million European nationals living in Britain after Brexit, and one million British expats living in the EU.

|

|

The two sides also want to ensure that Brexit does not exacerbate tensions in Northern Ireland, the once-troubled province that will become Britain’s only hard border with the rest of the EU.

Britain also wants to reach a new free trade agreement within the two-year timeframe, although it has conceded that a transitional deal might be necessary to allow Britain to adapt to its new reality.

Many business leaders are deeply uneasy about May’s decision to leave Europe’s single market, a free trade area of 500 million people, fearing its impact on jobs and economic growth.

The Brexit vote sent the pound plunging, although economic growth has been largely stable since then.

On Tuesday, Scotland’s semi-autonomous parliament backed a call by its nationalist government for a new referendum on independence before Brexit.

OPINION: If Scotland leaves, England will lose the Brexit game

Scotland’s devolved administration is particularly concerned about leaving Europe’s single market – the price May says must be paid to end mass immigration, a key voter concern.

The prime minister rebuffed the referendum request and has vowed to fight for a new relationship with Brussels that will leave Britain stronger and more united than before.

The EU, too, is determined to preserve its own unity and has said any Brexit deal must not encourage other countries to follow Britain out the door.

With the challenges ahead, there is a chance that negotiations will break down and Britain will be forced out of the EU without any deal in place.

This could be damaging for both sides, by erecting trade barriers where none now exist as well as creating huge legal uncertainty.

May has said “no deal is better than a bad deal”, and she has the support of pro-Brexit hardliners in her Conservative party who have been campaigning for decades to leave the EU.

|

|