Bolivians honour Che Guevara 50 years after execution

Thousands gather in the town of Vallegrande to commemorate the revolutionary’s life, death and legacy.

Vallegrande, Bolivia – In the remote corner of eastern Bolivia where Ernesto “Che” Guevara died, thousands gathered to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his death at the hands of the CIA-trained Bolivian military.

All four of Che’s children, along with Bolivian President Evo Morales and Vice President Alvaro Garcia Linera, and delegations from Venezuela and Cuba, came to pay their respects in the small town of Vallegrande on Monday.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTunisian lawyer arrested during live news report

Vladimir Putin sworn in for fifth term as Russian president

What’s at stake in Chad’s presidential election?

“This is a historic moment, not just for me personally, but for all peoples who struggle for their liberation,” Morales told the crowd.

“To remember the 50th anniversary of Che’s death is to remember the struggle for dignity and national sovereignty, and against imperialism.”

Visitors from all over the world attended the main event at the airport where the remains of Che and six comrades were found in 1997 and later repatriated to Cuba.

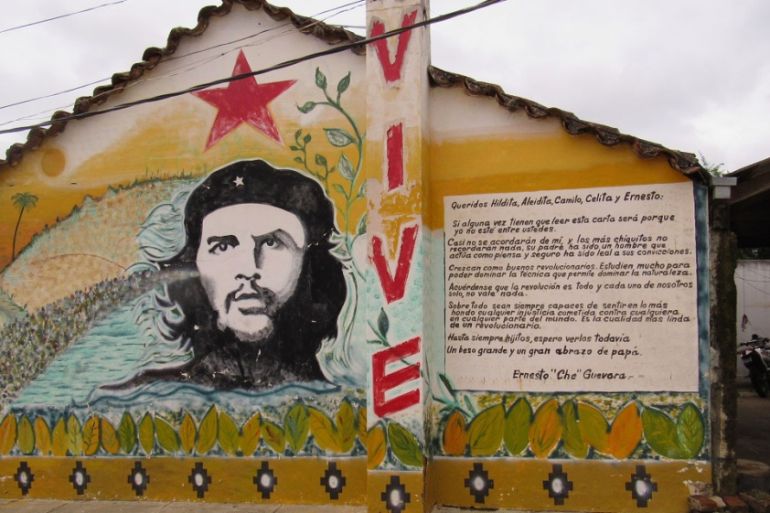

The nearby mausoleum and new museum show how the revolutionary icon transformed from being feared and hated by the Bolivian government to being praised by it.

![Thousands from all over the world visit the Che Guevara Mausoleum at Vallegrande airport every year [Linda Farthing/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/3f8f0f9b16cb4bce8d5bb9e914d0ce4d_18.jpeg)

Monday’s commemoration was part of five days of activities including film shows, theatre performances, photo exhibitions and talks.

“We are showing that in Bolivia, Che’s thought and his work are being kept alive and that our government follows his example,” said Alfredo Rada, Bolivian vice-minister of coordination with social movements.

‘We wanted to fight with Che’

Che saw Bolivia as a springboard to bring revolution to South America, and particularly to his homeland, Argentina.

But the ragtag band of revolutionaries he assembled misread the political moment in rural Bolivia.

Indigenous peasant farmers, released 13 years earlier from centuries of serfdom, supported a recently installed military dictatorship in exchange for guarantees that they would not lose their small parcels of land.

Nonetheless, some 20 Bolivian radicals joined his 52-member band.

“Many of us wanted to fight with Che, but no one knew how to contact the guerrillas,” retired mining leader Felix Muruchi told Al Jazeera.

“Even though our union was outlawed by the military, we managed to assist them with a contribution from our salaries.”

Fifty years on, Che has been turned into a marketable commodity – from t-shirts to fridge magnets.

This transformation meant that tourism could not be far behind.

The Che Trail

In Bolivia, the “Che Trail”, a multi-day route, was created in 2004 by the lowland indigenous organisation Asamblea del Pueblo Guarani, ironically with the help of the Bolivian military.

Guarani indigenous leader Nelly Romero, one of the organisers, said she believes Che would have approved of it.

“As Che fought for the poor, indigenous and peasants, I doubt it would have bothered him to have his name and sacrifice used by us,” Romero told Al Jazeera.

The loosely defined 300km trail traces the increasingly beleaguered band’s trip across densely forested Andean foothills.

The more popular northern route begins three hours west of the city of Santa Cruz in the picturesque tourist town of Samaipata, where Che received medicine.

It continues southwest to Vallegrande where his emaciated corpse was displayed in the local hospital and Tania, the only woman in the group, is buried.

![The laundry room in Vallegrande where Che's body was displayed. The sign above the door reads, 'Che lives on in the hearts and faces of those who demand justice' [Linda Farthing/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/121f38e8eedf4ae3a7a3636e3aa0c606_18.jpeg)

“Those tourists, who travel the Ruta del Che, are people who share Che’s ideals,” local guide Adalid Balderrama to Al Jazeera.

The final destination is the impoverished hamlet of La Higuera, where he was captured and assassinated.

Local shopkeeper Irma Rosales met Che’s group when she was 20.

“We had no idea who they were,” she said. “We were afraid of them because they weren’t from around here.”

Such distrust, combined with only token support from the Bolivian Communist Party, which favoured trade union and parliamentary work over armed struggle, ensured the group’s downfall.

Che could never have envisaged that he would become a sort of local saint.

“I come to light a candle and pray,” Emiliana Gutierrez, a teacher, told Al Jazeera as she stood outside the mausoleum where his remains were found.

“Che was a doctor and so his spirit has the power of healing.”

Farmers in La Higuera pray to Che for help with their crops, and residents often hang his picture in their homes next to Jesus and the Virgin Mary.

Bolivia’s current government is working hard to keep Che’s legacy alive, as are the people in this region.

“People die but their ideas never do,” said Morales as he walked to the site in La Higuera where Che was killed.

“We are in different times now, times of democratic liberation, fuelled not by the bullet but by the ballot box and the vote.”

|

|