Mosul strike survivors: ‘There were pieces of bodies’

Dozens of civilians died in a recent coalition strike aimed at killing an ISIL commander in Mosul, residents say.

Mosul, Iraq – It was just past 8pm on January 11 when an air strike killed Ebtisam Ataallah’s neighbours.

The intermittent electricity had come on a few minutes earlier – a rarity in the al-Amel district of ISIL-held western Mosul – so Ataallah, 44, had begun baking bread in a corner of their courtyard. Her four children remained indoors.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘Hell on Earth’ as violence escalates in Sudan’s el-Fasher

South Korean military says North Korea test-fired ‘ballistic missiles’

Western volunteers join the battle against Myanmar’s military regime

Two large blasts in quick succession knocked her to the ground, filling the air with dust, rubble and confusion. Inside the house, an external wall collapsed on top of her 16-year-old son Imran where he slept. He awoke covered in bricks and screaming, his leg badly broken.

In the now ruined room above him lay the body of a man thrown clear of the adjacent building by the impact, a young girl miraculously still alive in his arms.

Zaidan, 55, was having dinner with his family a street away when he heard the blasts. He rushed to the scene with his brother and two younger cousins.

“When we got there, we heard women and children screaming under the rubble,” the silver-haired 55-year-old, who declined to provide his last name, told Al Jazeera. “So, we went to help.”

As he extricated a young girl and took her to a nearby house, a third air strike hit, landing on top of the rescuers. His brother and one cousin were killed, and another cousin,19, was injured. Zaidan eventually found the top half of his brother’s corpse in the grounds of a school one block over; his legs were tangled in the remains of an awning over the Ataallah’s house.

![Two large blasts in quick succession knocked her to the ground, filling the air with dust, rubble and confusion [Cengiz Yar/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/4f18d216f969469db0ce8ed403020287_18.jpeg)

At least six households were wiped out in the strike, according to a number of witnesses. Those who combed the rubble for bodies said that they found the remains of 37 people, mostly women and children. They recognised all but two. A photograph said to be from the scene circulated by local activists showed a dusty, blood-covered baby wrapped in a red blanket.

All of the interviewees believed the target of the attack was Harbi Abdel Qader, a commander with the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant group (ISIL, also known as ISIS) – but added that he escaped unharmed in the few minutes before the third explosion.

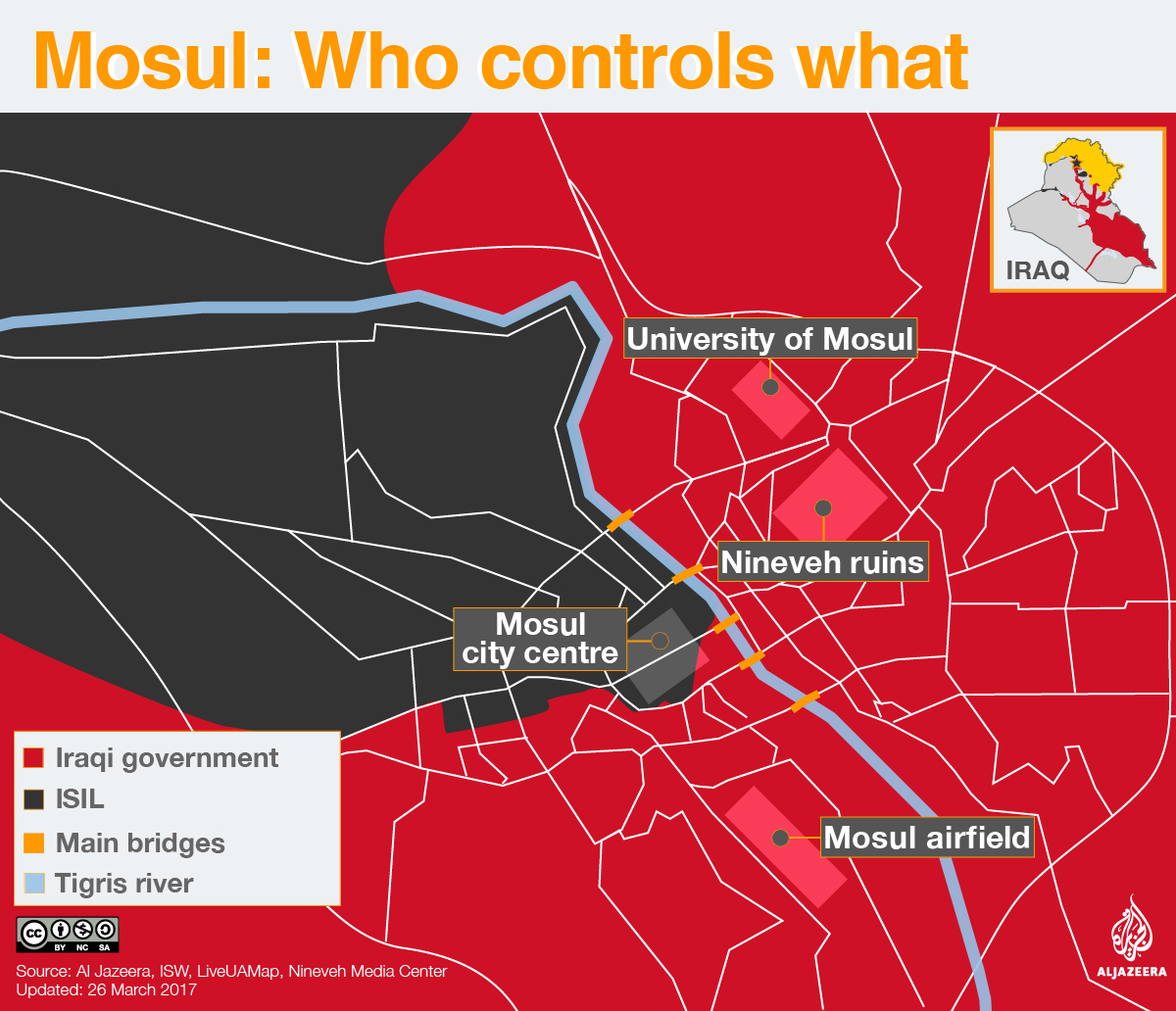

The substantial death toll in al-Amel was uncovered at a time when civilian casualties from both air strikes and Iraqi shelling appear to be mounting in west Mosul, amid international pressure for a swift resolution to the six-month-old operation to retake the city from ISIL.

On Friday, the US military said that its aircraft were involved in strikes on a nearby neighbourhood that residents said had killed as many as 200 people. Iraqi forces were still concentrating on clearing the armed group from the eastern half of the city in January, but civilian casualties due to air strikes were already being reported in the densely populated western parts of the city.

Now, as government forces push ISIL back still further, some of these blast sites are becoming accessible, including al-Amel, which was only cleared in mid-March.

The scene of the attack is still pure devastation. Individual houses have been reduced to twisted concrete and debris dotted with blankets and tattered items of clothing scattered throughout.

The US-led international anti-ISIL coalition has conducted hundreds of air strikes in support of the Mosul offensive, while the Iraqi air force has carried out its own, more limited operations.

A spokesperson for the coalition acknowledged reports of air strikes in Mosul resulting in civilian casualties on January 11 and 12, noting that while coalition forces “work diligently to be precise”, the January strike would be investigated further.

Coalition and Iraqi forces are required to operate under strict rules of engagement aimed at minimising civilian casualties. The coalition estimates that, as of March 4, 220 non-combatants have died in strikes it carried out since the international campaign against ISIL in Iraq and Syria began in 2014. Independent monitoring group Airwars suggests the figure is far higher, with as many as a thousand claimed deaths reported this month alone.

In al-Amel, residents said that, besides Qader and a low-ranking ISIL member, none of those who lived in the bombed area had any links to ISIL. Ataallah’s neighbour, Ali Khalat, moved there seven years earlier with his wife, children and grandchildren. They ran a small shop from their home and the older men drove a taxi to supplement their income.

It was Ahmed Khalat, one of Ali’s sons, who was blasted into the Ataallah’s home holding one of his daughters. She, along with her sister and brother, were the only survivors.

The two families were not close, but neighbourly, and the Khalats were well-thought-of in the area. “They were good people and they were taking care of each other,” Ataallah recalled.

|

|

At least five other civilian households were hit in the same strike. All were killed. The dead included Namis Salem Khadar, his wife Suha, and their two children, Sara and Sidra. The family can be seen in a picture recovered from the site dated June 4, 2012.

Apparently taken at a fairground, it shows Namis sitting on one end of a bench in a crisp white thawb and Suha perched on the other, wisps of brown hair escaping from a patterned headscarf. Sara stands between them, a small girl in red and white dress gazing solemnly at the camera.

Rakan Sukur, 48, was among those who helped to recover bodies from the rubble and line them up outside the house for collection by family members. A grey-haired man with prominent features and a black moustache. It was he who retrieved the family photo albums.

“You can’t imagine how I suffered to find these,” he said, describing how he darted in to grab them as heavy machinery worked to remove chunks of masonry. “There were pieces [of bodies] there, too.”

He and others were sure that Qader was not among the dead. The stocky, grey-bearded ISIL commander, who, in the neighbourhood, was said to have been an air force pilot under Saddam Hussein’s regime, was familiar to them and had even attempted to recruit local men.

“He used to come to the mosque and speak to us, encouraging all to fight,” Zaidan added.

READ MORE: Battle for Mosul upends false Iraq narrative

Last week, Iraqi special forces were still battling ISIL just 200 metres from the scene of the al-Amel strike. Bullets cracked overhead with great frequency, punctuated by the sporadic boom of artillery shells. The fight centred on a graveyard where some of the dead from the January strike had been buried.

Ataallah’s family has replaced the broken walls and windows of their home with stacks of breeze blocks that once made up their neighbours’ homes. It is a precaution against mortars, two of which landed in their courtyard recently, leaving black marks and shattered tiles.

Her son, Imran, still hobbles around on crutches. The room where he was buried for a time is still just rubble, and he points to the blanket that he was under when it happened.

“I had one breath there. I used it to shout,” he recalled. In a cast, his broken leg appears dark and swollen, and he dabs a handkerchief at an infected eye that will not stop watering.

The family understands what happened and who is responsible.

“We know what an air strike sounds like,” said 25-year-old Radwan, Ataallah’s eldest son. Seconds later, a jet called in by special forces roared overhead, reportedly to bomb an ISIL target a few blocks away.

Understanding why is harder.

“They killed most of our neighbourhood for one ISIL member and they didn’t even get him,” Ataallah said despairingly. “I don’t understand it.”