Rohingya crisis: A month of misery in Myanmar’s Rakhine

Monday marks one month since recent crisis began in Rakhine forcing 430,000 people to flee their homes to Bangladesh.

![Rohingya refugees wait to receive aid in Cox''s Bazar, Bangladesh. [Showkat Shafi/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/13c59db2d65e40ba8ddc7101e51ca42a_18.jpeg?resize=730%2C410&quality=80)

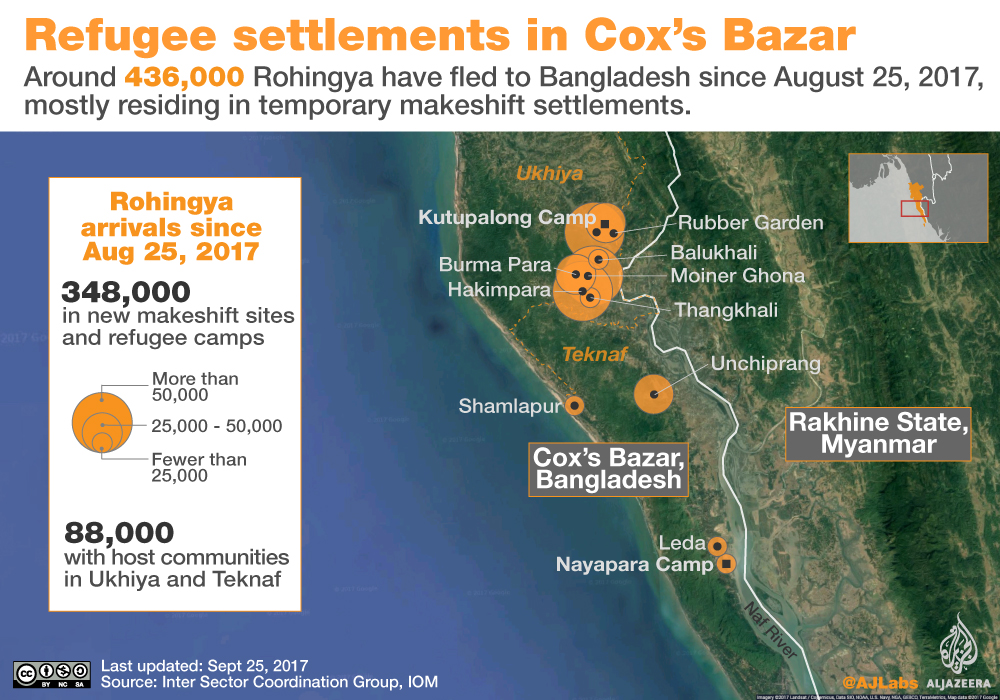

Hundreds of people continue to cross the border into Bangladesh one month since the start of the Rohingya crisis in Myanmar’s Rakhine state where raids by Rohingya fighters prompted a major army crackdown.

Since August 25, Bangladesh has been facing the unenviable dual task of looking after 430,000 wretched people while trying to persuade Myanmar to take them back. At least 240,000 of them are children.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsConflict, climate, corruption drive Southeast Asia people trafficking: UN

Bodies of three Rohingya found as Indonesia ends rescue for capsized boat

How is renewed violence in Myanmar affecting the Rohingya?

The influx adds to about 300,000 Rohingya, already located in camps around the Bangladeshi city of Cox’s Bazar.

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has earned praise for opening up the frontier to the desperate stream of humanity, but diplomats and experts say she cannot expect much international help in either campaign.

READ MORE: Myanmar – Who are the Rohingya?

They also warn that Bangladesh’s warm welcome so far could easily cool if solutions are not found.

“Bangladesh can’t deal with this crisis alone,” Champa Patel, head of Asia Programme at the Chatham House international affairs institute in London, told AFP news agency.

“It is densely populated, poor and already home to a historically displaced Rohingya community. While currently welcoming, this could change if the situation becomes protracted without any clear end in sight.”

There is not enough food, water or medicine to go around. Roads around the camps are littered with human excrement, exacerbating UN fears that serious disease could quickly break out.

|

|

“A shortage of basic sanitation means the ever-present risk of disease, and aid efforts are only starting to meet their needs,” said Al Jazeera’s Jonah Hull, reporting from Cox’s Bazar, near Bangladesh’s border with Myanmar.

The country has reacted with compassion to the horrific tales of rape and murder which refugees have brought with them. Scores of trucks carrying aid donated by the public arrive each day in Cox’s Bazar. But it is not enough.

The UN’s refugee agency chief has warned that the crisis may be long.

“We need to be ready for a problem that could last for some time,” Filippo Grandi, head of UNHCR, told Al Jazeera. “But we also need, as the prime minister of Bangladesh has said many times, to invest in a solution.”

“We cannot ignore that these people have a right to return.”

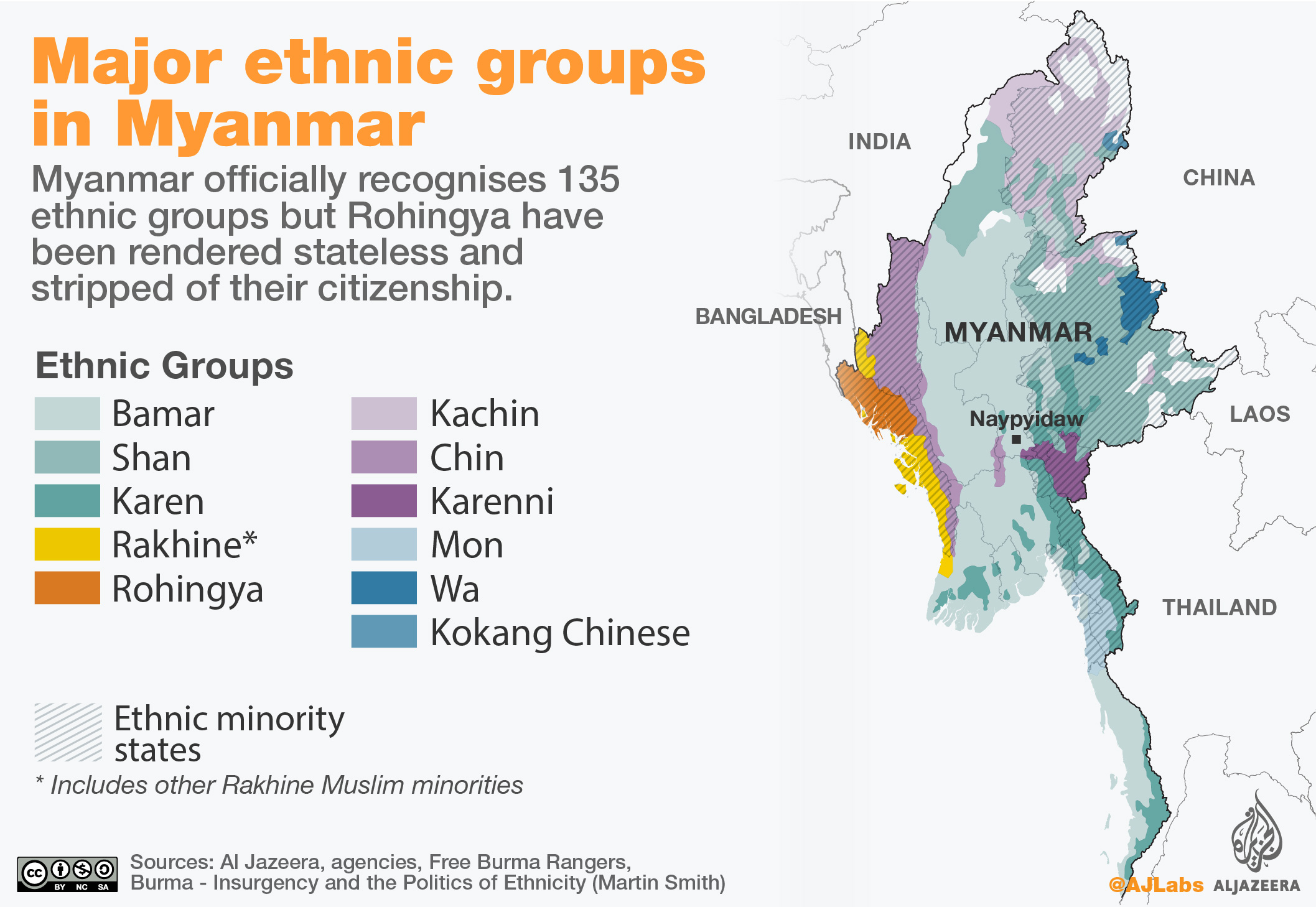

At the UN General Assembly last week, Hasina sought global help to solve the problems of the Rohingya, left stateless by Myanmar’s refusal to give them citizenship.

She called for the establishment of safe zones for the Rohingya. Myanmar has not responded.

Will Myanmar take them back?

Hasina wants pressure on Myanmar to force it to take back a group that has been in Rakhine for generations.

But neither Bangladesh nor the western countries who have been shocked by events in Myanmar have any real clout with its de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi or the generals who hold the effective power.

“The Myanmar army holds the key to resolve the crisis, in the immediate and short term,” Ali Riaz, a professor of Illinois State University in the United States and an expert on Bangladesh-Myanmar relations, told AFP.

“An extremist Buddhist nationalist political force has thrived in past decades in Myanmar,” Riaz said.

Bangladesh has “few effective instruments of statecraft at its disposal” to make Myanmar take back the refugees, according to Zachary Abuza, a professor at the National War College in Washington and a specialist on Southeast Asian security.

No regional group has shown a desire to get involved either. There have been demonstrations in Indonesia and Malaysia for the Rohingya. Both are members with Myanmar of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

READ MORE: Cox’s Bazar – Chaos all around at Rohingya camps

“Bangladesh could try to work with Malaysia and Indonesia to pressure Myanmar through ASEAN. But that is not going to work. The Rohingya issue is very divisive within ASEAN,” said Abuza.

China and India are the keys to influencing Myanmar, but neither seems likely to step in.

Both have supported the Myanmar government out of economic interest, said Patel at Chatham House.

They “have investments in the country that they would not want to be undermined because of the current crisis.”

The Myanmar generals are not listening to anyone anyway, according to Abuza.

“The Burmese military leadership has factored in the diplomatic costs of its actions. I think it is important to understand that they have been itching to do this for a long time,” he said.

Rohingya’s Muslims have long been ostracised in Myanmar, where they are considered “illegal immigrants” and face severe restrictions.

|

|