The City of Lost Girls

Diana Washington Valdez shares the insights she gained investigating the Juarez murders.

|

The ‘city of lost girls’ is the terrifying nickname for Ciudad Juarez, a Mexican border town, where more than 600 women have been raped and murdered over the past 15 years.

The story captured the imagination of a campaigning journalist on the El Paso Times. Journalist Diana Washington Valdez made it her business to lift the lid on what turned out to be a complex web of drug cartels and political corruption.

She joined Rageh Omaar to talk about her work that inspired not only the Jennifer Lopez movie Border Town but also a documentary by filmmaker Rodrigo Vasquez and reporter Sandra Jordan: The City of Lost Girls.

Diana shares the insights she gained investigating the murders and explains what happened in Ciudad Juarez since the documentary was shot in 2003.

|

Mexican soldiers patrol the streets of this border city as part of the federal government’s crackdown on the violent drug cartels.

Dozens of federal police and hundreds of local law enforcement officers form part of the contingent that’s working to reduce the power of organised crime in Juarez.

But, despite the show of force and presence of so many security officers, young women continue to disappear as a matter of routine.

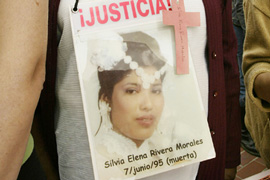

Sometimes, the only way to tell this is happening is by the flyers and posters in the downtown area asking for information about the latest missing women.

“It’s very serious that girls and women are vanishing with the authorities seemingly unable to do anything about it,” said Marilu Garcia Andrade, a member of Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa (May Our Daughters Return Home), an advocacy group that keeps pressing for justice for the dead and the missing women.

Her sister, Lilia Alejandra Garcia Andrade, 17, was abducted February 14, 2001, shortly after finishing her shift at an assembly plant. Several days later, people walking through a parcel near the plant came across her body.

According to an autopsy report, she was gang-raped and strangled. The FBI provided Mexican authorities with intelligence that a brutal drug gang that commits such murders as an initiation rite may have been involved. Eight years later, her murder remains unsolved.

| In Video |

|

|

|

Diana Washington Valdez talks about investigating the murders and the current situation in Ciudad Juarez |

Chihuahua state officials in charge of the murder investigations said they are following all potential leads.

Patricia Gonzalez, Chihuahua state attorney general, said only a small per cent of the murders are unsolved, and blames previous administrations for mishandling the investigations.

Over the past 15 years, more than 620 girls and women have been killed in Juarez, Mexico. Prior to 1993, such murders were rare in the city.

An uncertain number of girls and women are missing, and the number ranges from the 30 to 35 the authorities like to cite to the 250 figure the same authorities reported to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Drug cartels and corruption

What set apart the deaths that attracted world-wide attention is the brutality with which the women were killed. In some of the earlier cases, women’s breasts were severed, and their bodies mutilated. They were shot, stabbed, strangled, and dumped in ditches or vacant parcels.

Police and powerful people, including drug cartel members, were implicated. After 1999, a similar string of murders began to strike fear in Chihuahua City, the capital of Chihuahua state. None of the estimated 16 to 20 so-called “femicides” of Chihuahua City, which were eerily similar to the ones in Juarez, have been solved.

The film City of Lost Girls highlights the cases of Chihuahua City. Cynthia Kiecker, a US citizen, and her husband Ulises Perzabal, were accused in one of the Chihuahua City murders. They claimed police tortured them into confessing to a crime they did not commit, and spent 18 months in jail before they were exonerated and released.

Earlier this year, three Juarez mothers travelled to Santiago de Chile to testify at the hearing of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights about their daughters’ murders, which is part of the 2001 “cotton field murders” case.

Irma Monreal, one of the mothers, cried when she recounted for the judges the different ways Mexican authorities allegedly mismanaged the investigations and mistreated the victims’ families.

Mexican authorities also had their chance to present their case. To get as far as the international court, the families first had to exhaust all administrative and judicial avenues available in their country. Along the way their lawyers, family members and advocates were threatened to discourage them from pursuing the cases.

The court is expected to rule later this year on the case that has put the Mexican government on trial.

Spreading ‘femicides’

|

The “femicides,” as they are called, have spread throughout Mexico, and to countries in Central America and South America. They have turned up in places where the Juarez drug cartel and their associates work together to smuggle illegal narcotics.

Hester Van Nierop, a citizen of the Netherlands murdered in 1998, is among the many women who unexpectedly met with death in Juarez.

Similar methods of killing girls and women, most of who are not involved in high-risk activities, also have been reported in African countries where brutal violence against women has been used to terrify and intimidate communities and governments.

Juarez is a city of about 1.2 million to 1.5 million, depending on the ever-changing size of the floating population.

Until two years ago, between 250 and 300 assembly plants, most of them owned by Fortune 500 companies, provided the largest source of employment for people who live there.

It is located across the border from El Paso, Texas, a city of about 700,000 people with an army installation and hundreds of federal agents who guard the border. Its residents have a ring-side view of the violence and mayhem that have overwhelmed their neighbour to the south.

Ironically, El Paso is rated one of the safest cities in the US. Yet, in recent years, the US government has been remarkably silent about the ongoing murders of girls and women in Mexico.

“Despite the threats and attacks against us, we will not stop serving as a voice for the victims so that people never forget what has happened in Juarez”, Marilu Andrade said. “My family will not give up hope either that my sister’s case will be solved some day.”

Diana Washington Valdez is an author-journalist based in Texas, and author of “The Killing Fields: Harvest of Women”

City of Lost Girls can be seen from Thursday, July 16 at the following times GMT: Thursday: 0830 and 1900; Friday: 0330, 1400 and 2330