Cuba Calling

Change is slowly coming to Cuba. For one remote community and on one woman’s front porch, it is just a phone call away.

The changes coming to Cuba are taking many forms: private farms, small businesses, and new relationships with the wider world.

After decades of political stand-offs and economic isolation, there a tangible shift in how the country is viewed and how it views its relationship with the wider world. And how that change is being expressed is different for every community.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKing Charles unveils royal portrait

Cannes film festival hopes for ‘no controversies’ as wars, scandals rage

Energy summit seeks to curb cooking habits that kill millions every year

Tucked away in the Sierra Maestra mountains, far from Havana, stands a village caught on the cusp of the island’s legacy and the onslaught of technology in the 21st century. And for one retired lady and her neighbours, there is the possibility that change may happen on their own doorstep.

FILMMAKER’S VIEW:

By Juliana Fanjul

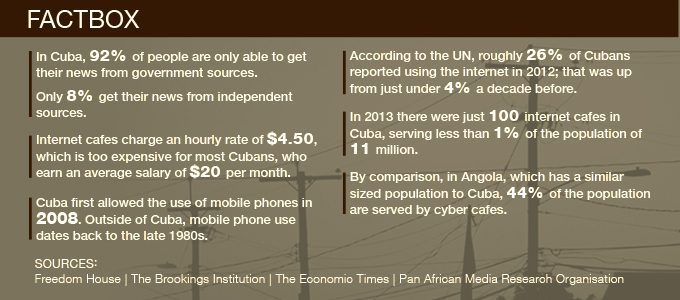

During the past few years, the world has experienced a digital revolution marked by a certain democratisation of the internet that has permeated almost every corner of the world. But, for various reasons, it turns out that there is a country in Latin America that is only just beginning the transition to this technological era; Cuba Calling is a film that witnesses this reality.

Almost 1000km away from Cuba’s touristic hub Havana is Varadero, where I found the community of Yao Vivero, hidden in the beautiful mountains of the Sierra Maestra. There, very generous people, mostly peasants and coffee farmers, hosted me.

I was immediately charmed by their hospitality and human warmth. But I was quite surprised to learn that one of the things they all shared was a telephone! One public telephone for one thousand people (approximately).

| JULIANA FANJUL | ||

|

And it was not exactly the typical phone booth that one can imagine, but just a telephone set, located in the house of a retired lady, Estrella, who had become her community’s window to the rest of the world.

It was 2008 when I decided I had to come back and make a film about this particular story. But it took five years before I found the means to produce the film.

However, during that time, I continued visiting Estrella and meeting more people from the community: Pucha, a beautiful 80-year-old woman whose family lives abroad, walked regularly to the telephone to wait for her only granddaughter to call; Nancy, a middle-aged woman whose only daughter lives in Italy; Jose, a blind singer who lives with his mother, or Carlos, a young man with emerging technology skills.

The shade under the tree where they all gather to wait and use the phone was probably the most important meeting point for the villagers, regardless of their generation, who – unwittingly – met there to chat, to exchange thoughts, to learn about one another’s lives. I was interested in the fact that this place was a naturally formed microcosm of Cuban society, and Estrella was the bridge between them and the rest of the universe.

By contrast, I could not avoid thinking about my own society and the compromises we have made by “digitising” ourselves. What impact has the use of technology had on our more basic relations? What have we gained and what have we lost by this new way of life? Has this “evolution” meant that I do not know anything about my own neighbours?

As I watched this tight-knit community, I wondered if the arrival of mobile phones may not only eliminate Estrella’s job, but also, little by little, erode the solidarity and trust among neighbours, and, eventually, make individuals more lonely and isolated.

What will the social costs of this transition be? How will it affect Pucha and the people from her generation? Will the elderly become even more left behind?

Shooting this film was only possible with the complicity of all the people from the community. I was very surprised that each one of them not only agreed to be filmed, but let us record their phone conversations. I remember we were there just a few weeks after the Snowden scandal, and I was very concerned about these people’s privacy. Working with a deep sense of ethics was, each day of shooting, one of the main objectives. So on many occasions I would take the time to explain the film to any newcomer. But it was very simple, people were not afraid, as many of us are when it comes to recording conversations.

Spending over a month without access to our regular devices was also a big lesson. By watching Estrella build a fire to toast coffee beans in her traditional wooden stove, I felt some nostalgia for what has been lost.

There is definitely a particular flavour that we like about “the past”. No wonder retro items have become so fashionable. From our wardrobes to our photographs, our watches or our bikes, there is this blues for the old that seems to want to fight against the rampant advance of technology.

Is it true then that “todo tiempo pasado fue mejor” (“all past time was better”)? In my opinion, at least in Cuba, you certainly get this feeling.

| In Pictures: |