Turkey and the Khashoggi saga: How Erdogan played his cards right

Ankara used the crisis to put pressure on a regional rival and recast its decaying relations with the US and the West.

Compared with the United States and Saudi Arabia, against the odds, Turkey appears to have gained the most out of the crisis over the assassination of Saudi Commentator Jamal Khashoggi. The fact that the kingdom of Saudi Arabia has had the most to lose is obvious, and the Trump Administration at best looks like it is caught between the Scylla of trusting an ally too much and the Charybdis of being an accessory by failing to heed bi-partisan pressure for accountability and mete out repercussions for the act.

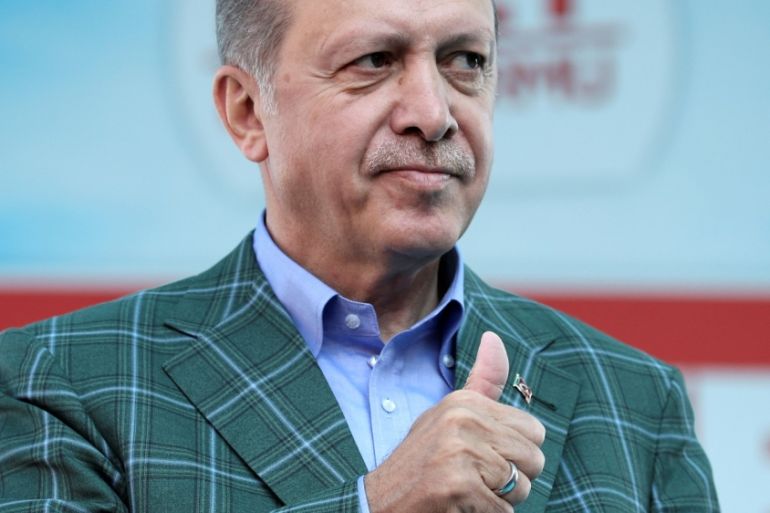

Whereas Turkey has skillfully managed the incident to its advantage, partly by putting pressure on Saudi Arabia and partly by using the crisis as a means to recast its relations with the US and the West. It is not in Turkey’s interest to have an ugly open diplomatic battle with Saudi Arabia, but Turkey does compete with it for influence in the Arab world. In addition, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan resents the foreign policy acts of Saudi Arabia as directed by the kingdom’s de-facto leader Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (known as MBS). While Turkey probably won’t cross the ultimate red line of lambasting MBS directly, by adeptly leaking damning details of the investigation to the international press it has put considerable pressure on Saudi Arabia and even appears to have knocked it down a few pegs in the international order.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMacron defies criticism to host Saudi Crown Prince MBS in Paris

Saudi Arabia, Greece to sign energy deal, Crown Prince MBS says

UAE arrests Khashoggi’s US lawyer on money laundering charges

In his first major speech on the topic this week, Erdogan described Khashoggi as “the victim of a vicious murder” and called for an independent international investigation into the incident. But while he used words of respect for King Salman, he did not refer directly to MBS by name. He called for the suspects to be tried in Turkey, as opposed to being protected by diplomatic immunity. He went on to ask a series of questions, such as where the body is and who the local collaborator is that Saudi Arabia says the body was handed over to. Moreover, he demanded to know who had ordered the operation, indicating Ankara is likely to keep the pressure on Riyadh.

|

|

Less expected, however, had been how adroitly Turkey – which has demonstrated a lack of skilled diplomacy in recent years – is showing the utility of crises by manoeuvring to put its relationship with the West, primarily with the US, back on an even keel. The release of the arrested American pastor Andrew Brunson was not the only indication of this diplomatic pivot, but certainly the most visible one. Turkey had arrested him on “terror” charges and refused to release him, even though it had unsuccessfully negotiated with the US in recent months over terms of releasing him in exchange for Washington agreeing to drop its sanctions-busting investigation into Turkey’s state-owned Halkbank.

Turkish relations with the West have deteriorated in recent years as Erdogan has grown more authoritarian domestically and more contrarian in dealing with fellow NATO allies. The Turkish president has long been frustrated by the EU’s insistence on deeper democratic and rule of law reforms, and more recently angered by the US’ unwillingness to hand over Fethullah Gulen, the Turkish Muslim leader Ankara believes to be behind the July 2016 failed coup attempt, to Turkish authorities and its support for Kurdish forces in Syria. Particularly after the unsuccessful coup attempt, Erdogan has moved closer to Russia, despite a Russian warplane being shot down by a Turkish fighter jet in 2015, and the Russian ambassador to Turkey being assassinated by a Turkish citizen a year later.

Other ways Turkey has been acting more in the interests of the West include how it is cooperating with the US in northern Syria in the town of Manbij, where it is coordinating patrols with the US in an effort to keep the Kurdish Syrian Defense Forces (SDF) out of the town – despite recent threats not to do so. In addition, Erdogan had a make-up meeting with Chancellor Merkel in Berlin. And most significantly Turkey pulled off a fairly miraculous forestalling of what appeared to be an impending Syrian-Russian-Iranian attack on Idlib that could have displaced and/or injured several million refugees living in the last major stronghold of the Syrian opposition. The most recent move has involved helping the West seek justice over the Khashoggi killing, with the Brunson release occurring in the first week of these efforts.

These unexpected pro-Western gambits certainly amount to something, at least an apparent about-face for Erdogan. Only recently he was railing against the US for its sanctions over Brunson, and the economic fallout for Turkey that has been so damaging. However, they prompt the question: does this represent a new pattern of cooperating with the US and the West, or is this merely a temporary means of giving Turkey its day in the sun ahead of a coming return to recent form of antagonizing the West whenever Erdogan finds it convenient?

Certainly, the US and its allies hope it is the former. For it was not long ago when Turkey had emerged as a regional superpower, the only democratic and capitalist Middle Eastern country and a willing bridge between the Muslim and Western world. This was early in Erdogan’s run as Turkey’s long-standing leader, first as prime minister and later as president. Turkey, during this period late in the Bush Administration and early in the Obama administration, was a net benefit to the global community, providing sturdy leadership and engaging in creative diplomacy such as helping bring a more lasting peace to Cyprus.

But as a US diplomat once memorably stated it, “dealing with Turkey is like peeling an onion” – meaning dealing with Turkish diplomats have always been difficult, as even if one matter got sorted out there would always be another one about which it would be difficult to find a communal way forward on. For years this was only the case in diplomatic discussions, such as in Brussels, but in the end Turkey could be counted on in strategic terms as a key member of NATO in a crucial region of the world. However, as President Erdogan began evincing autocratic tendencies, western relations with Turkey have grown more strained up through the recent era of Turkey repositioning itself as more an ally of Russia than its formal NATO allies.

Relations with Turkey have never been easy, but in the past even if Turkish officials proved difficult in diplomatic discussions, they often acted pragmatically in practice by, for instance, joining EU foreign and security operations on the ground with Turkish personnel and funding. In the age-old EU-NATO disputes involving Greece being in the EU and Turkey being in NATO, Turkey was often the more pragmatic of the two. But it may prove too much for the West to begin trusting its formal Turkish ally again, primarily because it is difficult to imagine President Erdogan resisting the next temptation to thunder against anyone at home or abroad who does something to annoy him.

Nonetheless, even just for economic reasons, it is in Turkey’s interests to maintain better relations with the West. And certainly, on some level, it must continue to appeal to the Turks, even to Erdogan himself, that Turkey – with some concerted efforts of the President and Turkey’s diplomats – could again take up the mantle of being a benign regional hegemon and once again a trusted bridge between the Middle East and the West.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.