Could coronavirus-induced recession be more deadly than disease?

How the economic downturn impacts life expectancy could boil down to the role you play in the global economy.

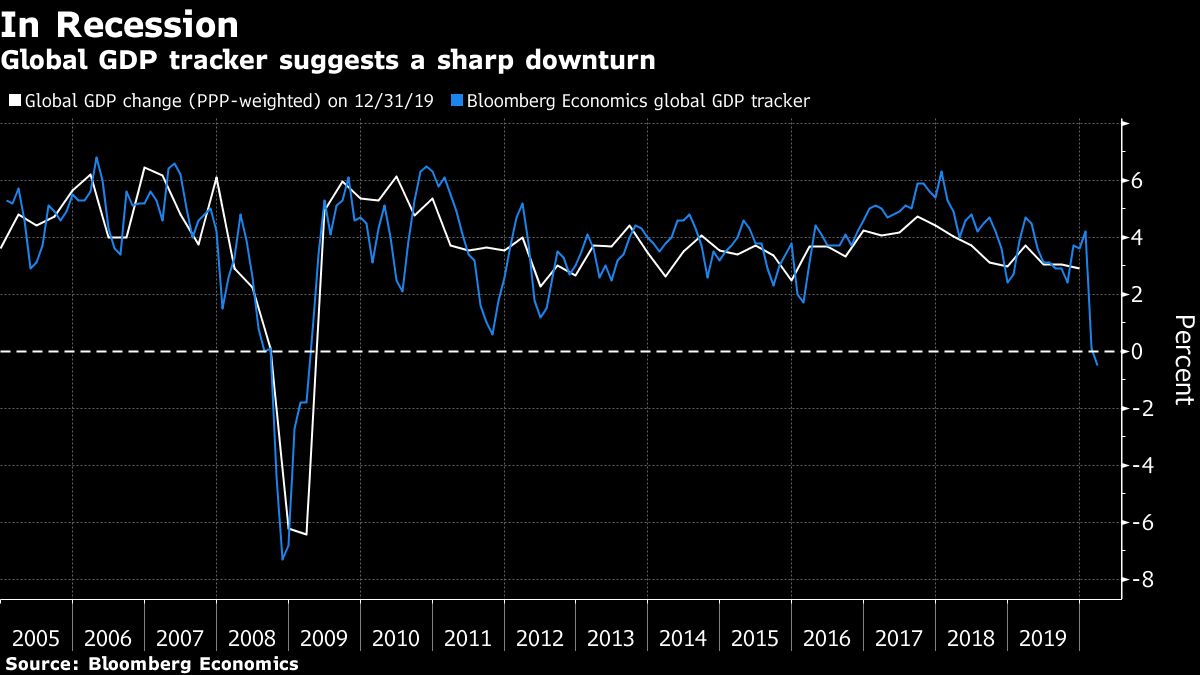

Just how deadly could a coronavirus-induced recession be? One recent study suggests the current economic slowdown roiling the world may end up killing more people than the virus itself. But some economists say the downturn could actually boost overall life expectancy. In the end, how it affects you could boil down to the role you play in the global economy.

United States President Donald Trump has seized on the likely lethality of a recession to argue that the US economy should be reopened as soon as possible.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

“You have suicides over things like this when you have terrible economies,” Trump said in a news conference on March 24. “You have death. Probably – and I mean definitely – would be in far greater numbers than the numbers that we’re talking about with regard to the virus.”

COVID-19 has so far claimed more than 100 thousand lives around the world, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Some economists believe that number could significantly increase if you factor in the financial fallout from virus containment measures that have shut down entire sectors of the economy and thrown millions of people out of work.

According to Philip Thomas, a professor of risk management at Bristol University, the coronavirus pandemic will severely disrupt businesses for at least a year, leading to a drop in economic output of 6.4 percent per person in the United Kingdom. In such a scenario, fewer people in the UK would be employed, and workers would generally bring home smaller paychecks. His recently published research concluded (PDF) such a downturn will lead to more deaths than the pandemic itself.

“It so happens that the UK experienced a similar drop, of 6 percent in GDP per head, between 2007 and 2009 in the financial crash,” Thomas told Al Jazeera. “This led to a stalling in the growth of life expectancy, cutting at least the tipping point figure of three months off average life expectancy.”

In his paper, Thomas showed that in the UK life expectancy flat-lined, and in some cases decreased, a few years after the 2007-2009 Great Recession. He reasoned when a country’s wealth declines, citizens are exposed to greater health risks.

“People in richer nations tend to live longer than those in poorer nations because they can afford to devote more resources to health and safety measures, which will range from provision of clean water and sewerage, to paying for safer working practices in industry, to the provision of high-grade medical services,” Thomas said.

But Thomas has his critics. And while they may agree that economic downturns affect health outcomes, other researchers have disputed how many people will be affected by a coronavirus-induced recession.

“The study jumps from [people in richer countries living longer] to assuming that the fall in GDP resulting from measures to suppress the pandemic would translate directly into reduced life expectancy,” said Jonathan Portes, professor of economics and public policy at King’s College London.

“That doesn’t follow – and in fact, we have plenty of evidence that short-term reductions in GDP don’t result in falls in life expectancy, if anything, the opposite,” Portes told Al Jazeera.

Are recessions good for your health?

Clemens Noelke is a research scientist at Brandeis University, whose work examines the relationship between recessions and mortality among older US adults.

“It’s difficult to extrapolate based on past data. It looks like we are heading into a severe recession, after a decade-long economic expansion in the US,” Noelke told Al Jazeera. “However, we do not, to my knowledge, have evidence on the impact of recessions that are flanked by a global pandemic. Based on the research we have on past recessions, we should, in fact, expect mortality rates to decline because of the economic downturn.”

The argument that recessions can lead to people living longer might appear counterintuitive, but Noelke explained that economic downturns could sometimes have beneficial health effects.

“During recessions, economic activity contracts, pollution declines, work hours decline, people have more time for themselves and others, traffic deaths decline, and deaths from cardiovascular disease decline,” Noelke said. “So, paradoxically, perhaps, a sizeable portion of the population experiences health improvements.” A lot of data supports those conclusions. Studies have shown that between 1960 and 2010, mortality rates in the US and UK declined by 0.5 percent for every 1 percent increase in unemployment.

Who dies could depend on economic role

That, however, is for the general population. For those who actually lose their jobs in a severe economic downturn, and for those who work in industries affected, deaths have been shown to go up.

“It is important to note that these impacts are very unequally distributed across the population,” Noelke said. “Many people lose their jobs, savings, and assets, and may not be able to recover from that. This is one factor contributing to a rise in suicide rates that occur during recessions, even as deaths from other causes decline.”

Governments in many countries, including the US and the UK, have moved to increase unemployment payments, and help companies pay employees, in an attempt to soften the blow of a virus-induced recession.

Noelke’s own research showed that older workers are more likely to die after losing their jobs, especially if they lose them during a recession. The loss of employment can lead to prolonged stress, which increases the risk of mental health issues and opioid abuse.

While Noelke disagreed that economic downturns translate into negative health outcomes for the general population, Thomas still believed that the threat is more general than some of the academic data may show. He said that the discrepancy is because the effects of recessions appear far later than a recession itself, so the data may not immediately show a jump in deaths.

“If you look at the data for the UK’s life expectancy, you will see that after the 2007-2009 crash there was a lag before the continuous growth in life expectancy that had been the norm for 30 years began to stall,” Thomas said. “If you had looked at life expectancy during the crash and, indeed, for the first couple of years afterward, you might have concluded that it was still rising … But the negative effect of the reduction in GDP was real, it just came a bit later, and it has been long-lasting.”