Currency wars: Trump and Warren push hard for weaker dollar

Populists say that devaluing the US dollar will bring back American jobs and boost domestic manufacturing.

What kind of American leader would want less bang for the buck?

More and more, it turns out. The idea of driving down the value of the United States dollar appeals increasingly to politicians and policymakers – both on the protectionist right and on the populist left.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKey takeaways from Xi Jinping’s European tour to France, Serbia and Hungary

Air Vanuatu goes into liquidation, thousands of passengers stranded

‘We have no option’: An election protest brews in Indian coffee capital

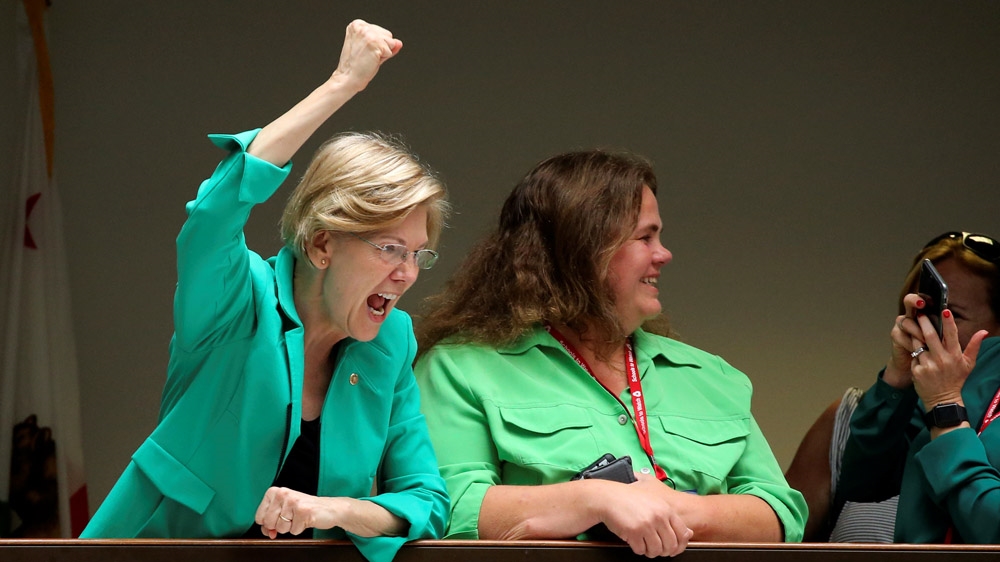

US Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts – a Democratic candidate for the US presidency – has proposed “managing our currency” to promote exports and kick-start domestic manufacturing.

A cheaper greenback could boost US exports by making the nation’s goods less expensive to buy abroad.

Warren’s plan for “economic patriotism” bears a striking resemblance to US President Donald Trump‘s suggestion that the federal government help the American worker by realigning the dollar, in an effort to lower the US trade deficit.

But three-quarters of a century after the Bretton Woods conference sought to end the practice of competitively devaluing currencies, economists vociferously disagree about whether the dollar should be weaponised in a currency war.

Critics argue that gaming the value of the US dollar- the primary international reserve currency and mode of payment – could unhinge the world economy, cause global instability, drive inflation and make stock markets tank.

The dollar was anointed king of world currencies 75 years ago on Monday by representatives of 44 countries who had gathered in Bretton Woods in the US to hammer out a blueprint for the post-World War II global monetary system.

One of the key objectives of the Bretton Woods Agreement was to bring stability to foreign exchange markets – and stop countries from competitively devaluing their currencies – by pegging them to the dollar, which in turn was tied to gold.

|

|

Over the decades since the first agreement, there have been several modifications. Most importantly, the US abandoned the gold standard in the 1970s.

But the dollar is still king.

As Trump instigates trade wars with China, Mexico, and other key trading partners, some economists argue that pushing the dollar lower would be more effective than tariffs at leveling the playing field for US exports.

They say that currency realignment is a better strategy for giving US goods a competitive advantage than levying import taxes on $250bn of Chinese goods.

‘Balance trade and capital’

Robert Scott, the director of trade and manufacturing policy research at the progressive Economic Policy Institute, has even been cited by Trump while making the case that imbalanced trade with China has hurt the workforce in the US.

Three main ideas are being advocated to realign the dollar. One, the US Treasury can impose a market access charge – a foreign investment income tax on capital inflows to reduce demand for US financial assets. Two, the US Federal Reserve – the US central bank – could purchase massive amounts of other currencies (called countervailing currency intervention). Or three, Trump could negotiate a temporary fix with major economies to realign the dollar with the yuan and euro.

Scott favours option one: “speed bumps” on foreign investment in US stocks, bonds, real estate and other assets to slow down cross-border transfers of currency.

To bring the dollar down from “unsustainably high levels”, he says the Fed – and central banks in other countries – should be “adjusting the tax rate(s) so as to balance trade and capital flows”.

Scott told Al Jazeera that his proposal to remedy imbalances includes a “dollar-adjustment system that was missing from the hard-dollar peg, [which] was the basis of the Bretton Woods system”.

Since central banks in about 20 nations, mostly in Asia, have financed their trade surpluses with the US by purchasing treasuries – and by extension have triggered the outsourcing of some US jobs – Scott says it is high time for “insourcing” to reverse the decades-long trend of production going overseas.

By his calculation, if the dollar were manipulated to fall by 25 percent overall – and potentially even more against the Chinese, Japanese and European Union currencies – the US trade deficit could decline by hundreds of billions of dollars annually. It is on pace to hit $700bn by 2021.

“Currency manipulation acts like an artificial subsidy to the host country’s exports and as a tax on all US exports,” Scott wrote just months after Trump took office, referencing China and others.

Currency manipulation acts like an artificial subsidy to the host country's exports and as a tax on all US exports.

China has been buying up US currency for years and now holds $3 trillion of foreign reserves and $1.12 trillion in treasury bonds.

One way countries drive down the value of their own currencies is by buying assets denominated in the currencies of other countries. And when countries buy US treasuries, they increase demand for such assets, which then drives up the value of the US dollar.

As US goods became increasingly uncompetitive, companies moved production from the US to set up shop in places where labour is cheaper, in part because workers are paid in currency that is weaker than the dollar.

Yet Beijing is far from the only nation manipulating its currency to prop up exports and cultivate domestic production. Trump himself has also called out Russia and the EU for this practice.

‘Avoid tampering with’ the greenback

Manipulating the dollar is not necessarily a panacea for the overall US economy.

Even though a strong dollar makes US exports more expensive around the world, it has been good for some US companies that rely on low-cost imports, especially retailers.

“Walmart, Costco, Apple, Amazon, Dollar General and other retailers that rely heavily on cheap imports would see their prices rise and profits fall. Boohoo,” said Scott.

That’s one reason Wall Street is against dollar devaluation, which prioritises workers over corporate shareholders.

Trade creates more wealth, but populists on both sides of the aisle have criticised trade deals in recent decades that have led to a disproportionate share of trading wealth accruing to business owners while workers fall further behind.

Proponents like Scott say, on balance, that currency realignment would increase US economic growth and government revenue because – though manufacturing only comprises eight percent of total US employment – it is 12 percent of total US economic output.

American labourers and exporters could potentially benefit from regaining a fraction of the 5 million manufacturing jobs that have been lost, in part due to the overvalued dollar – though automation has also played a significant role.

But if the US unilaterally devalues the dollar, other countries could follow suit, spawning a global currency war.

Still, economists of all stripes – including classical liberals and conservatives – are resistant to the idea of a currency realignment. One notable attempt was the partially successful 1985 Plaza Accord, in which the US and four other major economies agreed to devalue the US dollar to correct trade imbalances.

“President Trump and Senator Elizabeth Warren should avoid tampering with the value of the dollar directly,” David Beckworth, a senior research fellow with the libertarian Mercatus Center at George Mason University, told Al Jazeera. “Instead, they should appoint people to the Fed who would make decisions that would lead to a more properly valued dollar.”

Beckworth attributes the dollar’s recent rise to differences in monetary policy – a disparity in interest-rate targets – set by central banks around the globe.

In recent years, the Fed has hiked interest rates more than its central bank counterparts in other major economies, which has contributed to the dollar’s relative strength. The last time the Fed lowered interest rates was over a decade ago.

Last month, the Fed signaled rate cuts may be in the cards this year, thanks to economic uncertainty and ongoing global trade wars. Trump, meanwhile, has asked aggressively for lower rates to stimulate growth.

“To be clear, the Fed does not aim to manage the dollar, but instead strives to hit its ‘dual mandate’ of stable prices and full employment,” said Beckworth. “Nonetheless, easing by the Fed would indirectly cause – all else equal – a decline in the dollar.”

‘Hold the dollar’

Other economists worry that a weaker greenback would pose dangerous inflationary risks that could negatively impact average Americans.

“If the economy is at full employment like in the US, the cheaper dollar – if not accompanied by tighter budget policy – could result in higher inflation,” said Desmond Lachman, a resident fellow at the conservative American Enterprise Institute.

“Inflation, in turn, would offset the competitive benefits from a cheap currency,” Lachman told Al Jazeera, adding that US consumers would pay the price.

Lachman argues that a more responsible budget policy – with lower annual government deficits – would give the Fed leeway to drop rates without stoking inflation.

“Lower interest rates would make the US dollar less attractive, and would lead to its depreciation,” he said.

And when it comes to the international trade and currency framework first enacted in 1944 – and then altered several decades later – not everyone thinks it needs to change.

“The Bretton Woods System was modified in 1973 to deal with a world of floating currencies,” said Lachman. “It has served us well, and we should stick with it.”