Mass protests expose cracks in Chile’s ‘economic success’ story

The country’s prosperity, though lauded, has not been evenly shared.

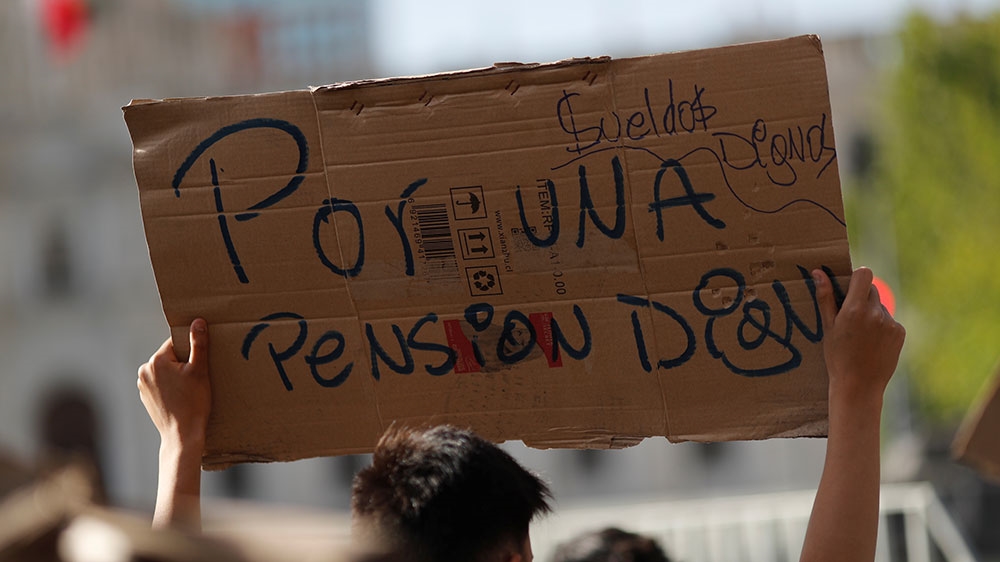

To understand the wellspring of discontent that exploded into violent protests across Chile more than two weeks ago, one should look no further than the placards held aloft by demonstrators listing grievances from rising transport costs and student loan debt, to paltry pension payouts and tone-deaf elites.

The wave of civil unrest that has so far claimed 20 lives and left thousands injured has laid bare festering resentment in a middle-income country lauded as a shining beacon of sound economic management, despite its failure to redress staggering inequality.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsChile unrest: Pinera backs out of hosting APEC and COP25 summits

Chile protests: More than one million bring Santiago to a halt

From a macro point of view, Chile is a success story. The world’s biggest copper producer, it has been among Latin America’s fastest-growing economies in recent decades and boasts one of the largest middle classes in the region.

Much of that growth can be attributed to market-friendly policies that have encouraged private enterprise, trade and investment and discouraged the government from spending beyond its means.

Chile has deftly avoided boom-bust traps that so often plague countries whose fortunes pivot on commodity prices. And it’s political system has proven remarkably stable since the reinstatement of democracy in 1990.

The results have been impressive in some respects. Chile is the highest-ranking Latin American country in the United Nations Human Development Index. The percentage of the country’s 18-million strong population living on $5.50 a day – the poverty threshold for an upper-middle-income country – has plummeted from 30 percent at the start of this century to less than seven percent by 2017, according to the World Bank.

But the prosperity that has helped lift millions out of poverty has not been evenly shared.

The fine print

The fine print of Chile’s success story reveals a Gini coefficient – a measure of income inequality – that is among the highest in the relatively affluent, 36-member Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Much of the wealth that accumulates to a narrow slice of the populace is not being redistributed effectively through taxes and benefits. Chile ranks second to last in the OECD for social spending.

Slowing economic growth and a depreciating currency have heaped pain on average workers and made even less money available for public services. Levels of household debt are high by regional standards and many Chileans have moved into less secure self-employment.

This is the backdrop of financial insecurity that is informing demonstrations that began as a protest against a subway fare hike and have since ballooned into widespread protests over inequality.

Citing a weakening currency and rising fuel costs, the government increased the subway fare by 30 pesos ($0.04). Though less than five cents in terms of United States dollars, the price hike proved a tipping point in a country where about half of all workers earn less than $541 a month, according to Sol Foundation, a think-tank.

One image that went viral on social media captured the conditions many Chileans say have been ignored by mainstream media in the three decades since Chile moved to democracy – a picture of an iceberg with transport costs at the tip and a list of financial hardships beneath the surface listed in English: “bad yet expensive education, a weakened public health service, a crisis in pensions, salaries, working conditions, corruption and scandals related to the misuse of public funds”.

Chile awakens

Marianela Denegri Coria, an academic at the University of the Frontier, said Chile “woke up realising that we are one of the countries where people have the biggest debts in Latin America, and where fundamental social rights such as education [and] housing are not guaranteed”.

She told Al Jazeera that is because such rights have been “privatised and are consumer goods that are increasingly hard to access”.

That privatisation is grounded in free-market policies implemented during the 17-year dictatorship (1973-1990) of Augusto Pinochet by the so-called Chicago Boys – Chilean economists educated under the tutorship of neoliberal economist Milton Friedman.

”[Chile

woke up realising that we are one of the countries where people have the biggest debts in Latin America, and where fundamental social rights such as education [and] housing are not guaranteed.”]

Pinochet’s dictatorship carried out structural reforms in all spheres, from the workplace to the courts and the Constitution of Chile, which remains in place to this day.

The five left-leaning and two right-leaning democratic governments that followed the end of Pinochet’s rule have failed to “significantly change” neoliberal policies that have led to a highly privatised economy, said Recaredo Galvez, researcher at the Sol Foundation.

“The dictatorship may have modernised the country, but it enjoys an unjustified recognition for growth, said Ricardo Ffrench-Davis, a Chilean economist. “Between ’73 and ’89, growth was mediocre and the distribution of income deteriorated considerably.”

“At the beginning of the democratic period,” he adds, ‘there was a big economic upsurge with seven percent growth rates … [but] in the decades that followed, this wasn’t kept up … [and] the transformative impetus was lost”.

Cancel student loan debt, boost pensions

Chile’s higher education system was privaitised in the early 1980s and it now has some of the highest average tuition fees in the world. This has forced many Chileans to take out student loans to fund university degrees – debt that can be negatively life-altering, especially when payments are missed and credit is destroyed.

Paola Tabilo, 29, divides her time between taking care of her two sons, a part-time job at a supermarket and writing the blog Mama Neurodiversa (Neurodiverse Mom), where she shares her experiences with her son who has special needs. She holds $28,000 in student loan debt for a history degree she was unable to finish – and earns $274 a month.

“I had a loan that I couldn’t pay and now I don’t have access to anything,” she told Al Jazeera. “I can’t get a mortgage, nor a credit card.”

Juan Pablo Rojas is the founder of Education Debt Coordinator, an organisation with 6,500 members – who are all demanding that their student loans be cancelled.

“A whole generation killed themselves financially,” he told Al Jazeera. “They could constitute up to around two million people with different loans.”

Chile’s pension system – also privatised in the 1980s – is another rallying point of discontent.

Administered by a handful of powerful private companies called AFPs, Chile’s pension system has some of the lowest average payouts in the OECD, with men receiving on average only 40 percent of their pre-retirement earnings and women only 36 percent.

In Chile, inequality is structural and it will take a long time to resolve.

Sixty-year old retiree Maria Angelica Ojeda made news in the weeks before the current wave of protests when she filed an appeal – the first of its kind – at the Constitutional Court of Chile, demanding access to her funds. She worked as a teacher for 30 years but retired on a monthly pension of $225 – not even enough to cover her monthly $300 mortgage.

Chilean President Sebastian Pinera, a billionaire, has pledged a series of measures in response, including a 20 percent increase in government-subsidised pensions directed at the poorest in the country. But his concessions have yet to ease public anger.

“Pinera’s so-called economic package is nothing of the sort. It’s a temporary measure but falls short of significant change,” said Dante Contreras, director at the Centre for Studies on Conflict and Social Cohesion.

“In Chile, inequality is structural and it will take a long time to resolve,” he told Al Jazeera.

As mass demonstrations continue and calls for Pinera to resign gather apace, it is unclear how Chile’s government will manage the crisis. Where there is a consensus is that this a nationwide movement a long time in the making and unlikely to taper off anytime soon.

“It will continue until the cause is addressed: it is not just about inequality, it is the brutal abuse, the distortions from the Pinochet era which have got worse during the three-decade long democratic period,” said Manuel Riesco, an economist at the National Centre for Alternative Development Studies. “The groundswell of civil unrest is strong enough to change that legacy, but it will take time.”

Maria Jose Vilches reported from Santiago. Marcela Pizarro reported from Doha.