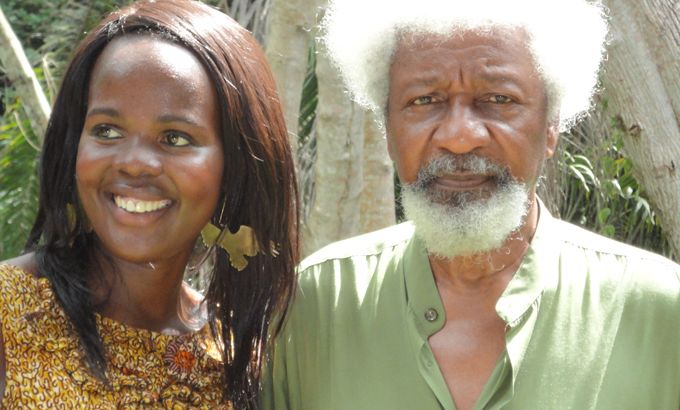

Wole Soyinka

The Nobel literature laureate talks about the end of colonialism and its impact on Nigeria’s identity.

Wole Soyinka is a writer, poet and playwright who was the first African to be awarded with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1986. His books and plays have won worldwide acclaim but he is also renowned as a political activist, being an outspoken critic of many Nigerian military dictators, apartheid, corruption, and political tyrannies worldwide.

Soyinka talks to Al Jazeera’s Yvonne Ndege about the end of colonialism and its impact on Nigeria’s national and ethnic identity.

Keep reading

list of 4 items‘No turning back’: Carnation Revolution divides Portugal again, 50 years on

Photos: Romania ex-prisoners fight to save memory of former communist jails

Rwanda genocide: ‘Frozen faces still haunt’ photojournalist, 30 years on

Al Jazeera: Can you describe what it felt like when Nigeria got independence, do you have any specific memories of that day?

Soyinka: Subjectively, I would be exaggerating if I said that I wasn’t caught up by the euphoria of the moment, but then I have to add that it wasn’t quiet as big a deal with me as maybe it was for millions of my country men and women and children. Perhaps the reason is that first of all I had always taken it for granted. That condition being subservient to another power, was something which never really sank in. […]

I never really personally underwent that experience of being subjects to another race, another nation, but of course as I grew older and learnt the history, it seemed to me an unnatural condition, it wasn’t real and in any case I grew up with the words independence and liberation, you know, I grew up with those words. So for me it was a question of not if, but when, that there was some kind of administrative ritual which had to be gone through. […]

I listened to lots of conversations between my father and his intellectual circle, in the direction of the colonial powers, the world war was involved, the arrogance of the European nations towards darker skinned races. All of that was part of my upbringing. It was always something that had to eventually happen and so when it eventually happened it was like, what’s all the fuss about? This was inevitable.

You felt there was a sense of euphoria amongst, how did that manifest itself?

I’d like to say that, you could almost say that their shoulders became straighter and the language towards the departing power representatives became stronger, more confident, and there’s something about lowering a flag and raising another one, which no matter how hard-boiled you are is really an emotional moment.

That solemn moment when they salute the military, the police, polititian’s standing in all their finery and then a flag goes down and another is raised, that moment I remember very very well, if the moment of independence finally got through to me as something really to be celebrated I think that was it.

Can you briefly touch on your own family’s involvement in the nationalists movement towards independence?

The political life of my family in which I grew up began with the eternal struggle against feudal system. I had an aunt who led a woman’s movement against the autocratic conduct of the then monarch of Abugida, the imposition of taxes, the harassment of women by the tax collectors etc. She and her husband used to talk in a strong language of anti-colonialism, and I used to listen when I was a child and took interest, for instance in the war. I distinctly remember when the atom bomb was detonated over Japan, the anger of my aunty on the phone to the district, district officer saying to him never drop certain lethal weapon on one of your own people, you had to do it to Japan, because you don’t consider them human beings. I remember that discussion which of course brought me to the consciousness of serious profound race issues.

My mother became involved in the women’s struggle against the feudal rather autocratic monarch, and I came in somewhere there running errands between the various women’s groups prizings. But most of my mentorship my absorption of political issues came from the circle of my father, he used to have a constant debate with his colleagues on every subject on the earth including even the cut suit they ordered from England.

Can you explain what colonialism felt like, how it manifested itself? There are so many of us that cannot imagine a world in which a country like Nigeria or Kenya was ruled from Britain.

It’s amazing, I had the same feeling when I was in England not long ago, not for the first time, and I looked at the history of England, the architecture the level of development the sociopolitical life there, I used to say it beats me how a tiny nation like England actually presumed to travel overseas and controlled this huge ancient civilisation.

Even though I came up as a colonial person, if you transfer that to Nigeria you begin to understand why that sense of being a colonial subject never percolated to me. Right, on occasions like empire day where we we sang these praises of the queens and kings of England, and we knew that from time to time that we interacted with district officers.

In terms of what’s around we lived such a mixed indigenous lives with Christian infusion and it seemed like the most natural thing in the world, it’s a meeting of various cultures.

Everything was quite normal but there was an issue, which would be sorted out, which just expunged those who didn’t belong there in the first place from our nation, that was the only way I related to colonialism.

In one sense colonialism emasculated Nigeria, and independence freed Nigeria to be what it was supposed to be …

I wouldn’t use the word, suppressed the potential of Nigeria, yes, that I would agree with, but since that really was not completely it was merely suppressed for some time, I wouldn’t say the nation was emasculated as a result of colonialism.

I’d tell you what the colonial experience did to Nigeria – the consequences are pretty much still with us. The British made up their minds to which section of the nation power would pass on their departure. Which meant that they wanted to be sure that it was the, shall we say, least radical section of the country.

To that end, and these are facts which are now out in the open with the end of the period and the memoirs of the former colonial officers, who were ordered to falsify not merely the results of the first election. We put the politics and economics of this nation we built and this was denoted deliberately distorted by the departing British. So in that sense something really unpleasant took place as a consequence of the colonial experience.

Do you think the then leaders, people like yourself even had a sense of what Nigeria was going to be?

We had a very intelligent leadership, during that time, the mixture the prominent ones were very methodical politicians and national leaders who actually planned, not only planned but outlined their plans.

Attention was being paid to the cultural vitality of nation, of the region, and there was a sense of competition, a sense of competition between the regions. If the west let’s say started a free education for all children at primary level, the east would respond with maybe something a bit more modest but just as progressive as well, and the third [region] then would respond saying nomadic education, so there was this sense that there is one thing to ensure that the regions were not left behind. So we saw it, we knew how it would be done, so it was actually being done.

The food production, the export level of food from Nigeria will not be believed when you realise that today thanks to the mono economy of petroleum agriculture has been so neglected, that food is being imported, rice is being imported from Indonesia, [… ] but at that time there was a real will to succeed to demonstrate to the departing British and other colonials, the we never needed them anyway. There was that nationalist mood.

Do you ever feel a sense that maybe Nigeria was not ready for independence?

I would never agree with that because in any phase in people’s development they are already potentially endowed to be independent. This is something I passionately believe. Any other thing is grotesque, is a contradiction in terms.

There were nations in Nigeria before the British came and distrorted the political traditions of those societies. The economy of the colonies were geared for the production facilities for the manufacturing development of the colonial nations. Cotton, we used to make our own clothing. With colonialism the cotton was being geared for the cotton mills of Manchester. In other words the raw materials and the production was geared at an external society, external consumer needs and commodity.

Farmers were now compelled to just grow cash crops rather than the basic food self-sustainability requirements. In that sense I do not agree with the fact that independence came too early. It could not have come too early. Nations which had evolved organically had been amalgamated. And groups, nation groups which had traded organically and had created their own economic systems for centuries were suddenly cut in two abruptly. One-third went this way, the other third went the other way. Artificial nations. Most of todays so-called African independent nations are artificial creations of the British. Not just the British, also the French, the Belgiums the Portuguese – and they created a mess. The consequences are still very much with us.

Nigeria did not have a big leader like Kenya, for example, do you think it was a good thing or a bad thing in terms of forging the sense of national identity?

First of all the premise I think is not totally accurate. European political information system follows very often the economic pattern. When the British required a strong man to follow in their footsteps they created one. And sometimes one was created by default by sheer charisma and energy. We had remarkable leaders, household names even if they weren’t even that known in foreign parts.

Some say the greatest impact of colonialism is the psychological impact, the destruction of African self-believe. Do you believe this to be true in Nigeria?

I don’t believe this is true in Nigeria but it would be true of certain other African countries. The reason is that Africa has had different types of colonialism, there was settler colonialism, the assimilation colonialism and indirect rule.

Indirect rule is what we more or less had here. With indirect rule people kept closer with their roots their history and their self-knowledge. The worst was the assimilation, which is what the French practiced – trying to turn their colonial subjects into Frenchmen. The British believed that the Africans were ‘too stupid to absorb our culture anyway so let them stay in their primitive arena.’ So we had these different forms of colonialism. I don’t think it’s true in the case of the self-confidence of Nigerians in their own history and by that time in the Yoruba the Hausa, the Igbo etc. The self-confidence has always been there.

After independence you helped form the sense of Nigerian national identity. Do you think you were successful?

Well when it’s claimed that I helped form a national identity I suppose it was largely an unconscious thing. For instance I consider myself a Yoruba before I’m a Nigerian. That’s my immediate instant identity. And I think most intellectuals will say the same thing, and politicians. However, here we are together brought together by the British. Operating the same constitution. A new identity that supervenes the various ethnic nationalities is born. So one responds through ones literature, ones writing, ones political activism to all that. It’s almost an osmotic process.

I don’t believe that I set out to create a Nigerian personality. Yes, I used the expression Nigerian, and Nigerians got excited over Nigeria at the World Cup. I carry a Nigerian passport and I get angry if anybody tries to denigrate or reduce it in any way and so you have a second corporate identity, which becomes just as important as the first identity. Because this is the one you represent to the world and this is the one, which is essential to cohabitation and development along political, cultural and economic lines. So if you say I helped to form a Nigerian identity I would say that I did it unconsciously as the most logical process in the world.

Do you think there’s a sense of national identity first, or ethnic identity or religious identity? What does the average Nigerian feel they belong?

The average Nigerian these days never believes in the leadership language of a single identity. Because they see the leadership acting in a completely contradictory way. But that is not to say that for instance at the time of independence that Nigerians did not feel a powerful sense of identity. What contributed to the euphoria was that we are now recognising ourselves as one people in our own right. But this sense of identity, the possibility of really forging the possibility of an identity has been severely battered. Anybody who says opposite is living in a totally different world. But I think they feel a dual identity. Same as myself. Mine is a dual identity, a national and ethnic identity.

What about religious identity?

Religion no. To me Islam, Christianity, these are all foreign colonial religions anyway so I don’t have any allegiance. Even though I was raised in a Christian home I don’t feel the slightest sense of identity towards Christians any more than I do with Muslims.

But do you think Nigerians do? Do you think some people feel that they have to identify themselves along religious lines, to feel safe, to feel part of Nigeria?

I regret to say that some do. I know people who have changed their names in order to get contracts during a period when it was a leadership that came from one side. They knew that when their names sounded this way they would be more favourably examined and responded to. You have that to. Nobody is going to deny that.

I distinguish, and I think most Nigerians do, between general religionists and the fundamentalists adherents. I think Nigerians are beginning to realise that it doesn’t matter what religion you profess, the danger within that religion is constituted by the extremists and the extremists are the enemy of the entire Nigerian people.

Is Nigeria a democratic nation?

Not yet. Not at this point no. It’s a spiral. It’s a cyclic thing. You go into power, steal money and you use that money to perpetuate yourself in power so you have to steal more money. The only difference is that you accumulate now a lot more dependence and so you gradually build up an army of faithfuls who rig elections for you, who commit political assassinations for you, who manipulate the banking system, who bankrupt your enemies, etc. Nigeria is very close to being another Colombia where you have a cartel. Not a cocaine cartel but a wealth cartel to protect one another to scratch one another’s back. To support one another in order to retain power.

You have been talking about many problems here, but there is still a dynamism, and an energy in Nigeria. Where do the Nigerian people get the tenacity to go on?

Sometimes civil society goes to sleep for a long time and wakes up and realises that the world has really moved beyond when it went to sleep and then it becomes angry. And things happen and sometimes hopefully, it happens in an organised way. Right now civil society is waking up and one is observing and participating with cautious optimism. If you fix democracy for instance, Nigerian people are very politically sophisticated and very knowledgeable they know a lot more than the leaders think. So it becomes easy to mobilise, to lend support for the efforts being made to sanitise the nation.

That resiliance is what has brought us through several economic crises. One leader, Babangida, was moved to say it at one time but he didn’t understand how Nigeria was still able to survive economically, it should have collapsed economically a long time ago, that’s the president of the nation.

And it’s that driving energy and the determination not to go under that’s rescued Nigeria again and again. But I think the Nigerian people have reached a point that say wait a minute, we elected people to sort this problem for us and they feel and we have to make up the deficit that they have made the nation incur by stealing what we have produced and I think it’s that consciousness which is beginning to effect being manifested all over the place right now.

What is your feeling about the upcoming election?

Not only are Nigerians very politically sophisticated but in terms of manpower it’s an over-endowed nation. You can walk into any town, you can look in any town, and find half a dozen people who are fit to run the entire nation. And so my concern is simply to make sure that the people get the chance to recognise such individuals and to elect them to office – and to have their choice respected.