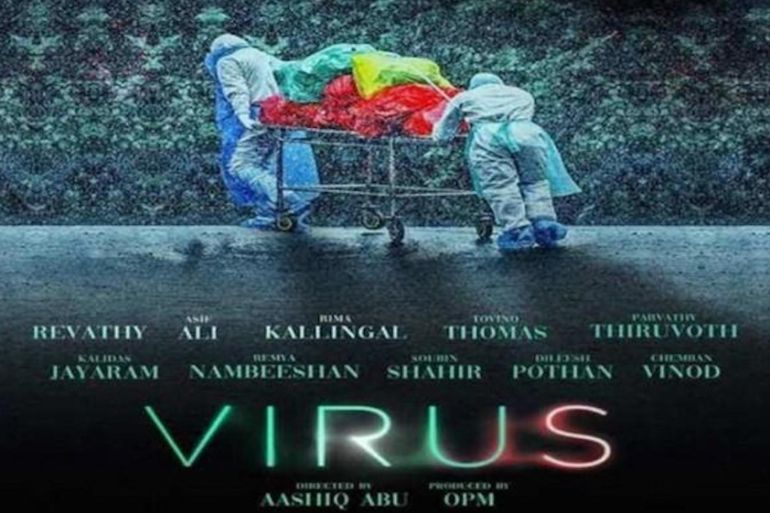

Virus: A lesson from Mollywood on how to tackle coronavirus

The 2019 film on Kerala’s Nipah virus outbreak offers a blueprint on how to effectively stem the spread of COVID-19.

“You are all heroes. At a time like this, did you not come as soon as I asked to meet you? … In the last several hours, this land has surprised me no end. We did not have enough ventilators – they were provided to us by private hospitals. It is difficult to arrange for the minimum of 800 PPE kits we need per day. But early this morning, PPE kits worth around Rs 80 lakh arrived at our airport – a local industrialist friend got them here in his own aircraft with his own money. This morning, when Dr Sridevi from the medical college stepped out to get her newspaper, an unidentified man was waiting for her with a whole bundle of N95 masks. He handed them over, saying, ‘Doctor, you will need these’, and left without even telling her his name. You may not think twice about any of this because you are natives of this city, but for me, these are all miracles.”

Does this sound like a heartfelt speech delivered by a politician during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic? Well, it is not.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWatching The Message during Ramadan

Around the world, cinephiles say ‘meh’ to Hollywood’s Oscar nominees

Malaysia charges two with ‘wounding religious feelings’ in now-banned film

This is a monologue from the critically acclaimed 2019 Mollywood hit Virus. Mollywood, the nickname for the Malayalam language film industry based in the southern Indian state of Kerala, is not as widely known internationally as Bollywood, but it is held in high esteem by cineastes and critics within India. The speech I quoted above was delivered in the film by Paul V Abraham, a bureaucrat in Kerala.

In the scene, Abraham is trying to convince ambulance drivers to continue transporting patients to hospitals amid an outbreak of the deadly Nipah virus. One of the drivers is upset because he feels their justifiable hesitation to continue with their work has been misrepresented. “If something bad happens to us during a trip, who will look out for us?” he asks. “I’m just saying this because we are being painted as villains.” Abraham’s speech is a response to this lament, and with it, he convinces everyone in that room to resume work.

Virus is based on a true story. It is a retelling of Kerala’s 2018 battle with Nipah, a deadly virus that is zoonotic (transmitted from animals to humans) and can also be transmitted through contaminated food or directly between people.

In May 2018, when Nipah struck Kerala, which is admired across India for its lush greenery, high literacy rate and other progressive human development indices, the authorities were well aware of the damage it can cause. The virus killed 105 people in Malaysia in 1998-99 and forced the authorities to order the culling of 1.1 million pigs, which led to debilitating trade losses. It also killed dozens of people in different regions of Bangladesh between 2001-2015 and in India in 2001 and 2007.

Two decades after its identification, there is still no vaccine to prevent the spread of the Nipah virus, although the World Health Organisation (WHO) has placed it on a list of “priority diseases” for which “there is an urgent need for accelerated research and development”.

Kerala has a high population density. So when the first few cases of Nipah virus were identified in the state two years ago, many feared that the disease could spread rapidly. It would have calamitous consequences for the local population, the economy and India at large.

The state administration, however, swiftly swung into action and contained the outbreak at its onset. In June 2018, less than six weeks after the identification of the first Nipah case, the only two affected districts in the state were declared Nipah free. Seventeen people had died by then, but the local government earned praise in India and abroad for speedily stopping a localised outbreak from turning into an epidemic.

Virus, directed by Aashiq Abu and written by Muhsin Parari, Sharfu and Suhas, recounts the clinical efficiency with which politicians, bureaucrats, the healthcare fraternity, sanitation workers and the public joined hands to nip the tragedy in the bud.

Abu’s film is a far cry from the 2011 Hollywood flick Contagion, which has been an object of global fascination since the novel coronavirus began gradually extending its grip across continents this year. Cinephiles have been struck by what appears to be the film’s foretelling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Director Steven Soderbergh’s star-studded medical drama is about a far more lethal contagion than the novel coronavirus and the social chaos it causes. The anarchy and devastation portrayed in Contagion bear an uncanny resemblance to what we are experiencing today. The film fills audiences with dread by showing them how bad things can get during a pandemic.

Abu’s Virus, which belongs to the same genre as Soderbergh’s Contagion, has a vastly different impact on the viewer.

“After watching Contagion, you are afraid to touch a lift button or your face. The film leaves you with a fear,” Abu told me when I interviewed him for this write-up. “We decided that our film should give people hope, not fear.”

To offer that hope, Abu did not need to delve into fiction. The news media had widely chronicled the Kerala government’s meticulous response to Nipah in 2018. The director and his team also spent several months on research, meeting bureaucrats, medical professionals, Kerala’s health minister, scientists and the other real-life characters depicted in Virus.

In his film, Abu merely transposed what actually happened in Kerala during the outbreak to the cinematic medium and portrayed with precision how the state’s leaders and medical professionals treated those infected by the virus, identified and quarantined individuals who had been exposed to them, investigated their links to Patient Zero, painstakingly tracked down the original source of the virus and prevented new infections, all the while coordinating with the central government in New Delhi.

Watching the film now not only allows audiences to see what could have happened if political leaders responded to the outbreak of COVID-19 the way Kerala authorities responded to the Nipah outbreak in 2018, but it also gives them hope by demonstrating that even the deadliest outbreak can be contained with efficient leadership and hard work.

Therefore, during the coronavirus pandemic, there are lessons to be learned from Virus and the real-life events on which it is based.

In Virus, multiple-award-winning actor Revathy plays Kerala Health Minister CK Prameela – a character based on the real-life Kerala Health Minister KK Shailaja who led the state’s anti-Nipah taskforce in 2018. Revathy told me in an interview for this article that the film portrays “the maturity and responsibility” with which the minister and her associates tackled the Nipah outbreak, and presents a blueprint for how to effectively respond to future outbreaks.

Revathy also said she believes the film can serve as an educational tool amid the ongoing pandemic. “How a virus can spread is beautifully mapped out in the script,” she said, “watching it now can help us understand, for instance, how coronavirus can stay alive on certain surfaces for a certain number of hours and so on.”

“The film basically tells us to stay safe by following the guidance of doctors and the WHO and not to panic.”

Awareness-building was one of the goals Abu and the scriptwriters had in mind when they chose to make Virus a medical procedural rather than pivoting its plot around a single individual’s poignant experience.

The story of 28-year-old nurse Lini Puthussery, who died after treating Kerala’s first Nipah patients, for example, could have easily been at the centre of the film. The touching farewell note Puthussery wrote to her husband when she fell ill with the virus had made the rounds on social media and was even reported on by national newspapers and websites. Abu said he was first drawn to the story of Kerala’s Nipah outbreak when he read about Puthussery on social media. A conventional approach might have been to build the film around the suffering and sacrifices of a nurse who captured the hearts of the Kerala public.

Rather than using Puthussery’s tragedy as the primary ingredient in a soppy tearjerker, however, Abu opted to make a film about the community’s successful response to the virus.

The Nipah outbreak, he told me, “happened in a community, in a state, so we thought we should tell the story on a bigger canvas, because it was a huge effort, so everyone should be complimented or referred to”.

Virus’s star lineup was also assembled to underline the teamwork and community spirit that got Kerala out of the crisis. “We wanted to pay respect to the heroes and victims, so we tried our best to get in as many familiar faces, as much star value to each and every character as we could,” Abu explained.

Award-winning actor Rima Kallingal, for example, played nurse Akhila – a character based on Puthussery – in the film. Tovino Thomas, a young matinee idol, played Paul V Abraham, the bureaucrat mentioned at the start of this article. His character is based on UV Jose, the then collector of Kozhikode district.

Despite its ultimate positivity, Virus is not a tale of sugar ‘n’ spice and all things nice. It is a tension-ridden suspense saga that, among other things, tails a student of community medicine (played by the popular activist-cum-star Parvathy) and a senior virologist (Kunchacko Boban) as they try to identify “patient zero” and understand how he caught the deadly virus.

Virus also features closed-door meetings in which New Delhi is shown putting pressure on the Kerala government to view the Nipah outbreak in the state as an act of bio-warfare. The film portrays the central government’s representatives focusing on the supposed patient zero’s travels to the Middle East and the increasing interest he demonstrated in religion before contracting the virus. The man’s name makes it clear that he is a Muslim.

The film leaves it to the viewer to decide whether Islamophobia played a role in the central government’s suspicions about him, but it raises important questions about how politics shapes the authorities’ response to a disease outbreak. India’s central government is led by the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), whereas the Kerala government is headed by a Communist party that prides itself on its secular values.

In some ways, Contagion is about what not to do during a medical apocalypse, while Virus is about what to do to avoid one. As mental wellness experts underline the need for optimism in these troubled times, it is worth wondering whether Contagion, as gripping as it may be, is an ideal watch when real-world events are increasingly mirroring the disastrous developments in the film’s storyline.

If you are looking for cinema in the same genre that will not psyche you out in the middle of this health emergency, Virus – uplifting in comparison – is a safer option. Contagion, after all, is a hypothetical worst-case scenario, while Virus is a best-case scenario inspired by a true story. Contagion is about the devastating spread of a disease, Virus is about how the spread of a deadly contagion was efficiently stemmed. Most importantly, Contagion is about the worst that human beings can be during a catastrophe, Virus is about the best that we have been while averting one.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.