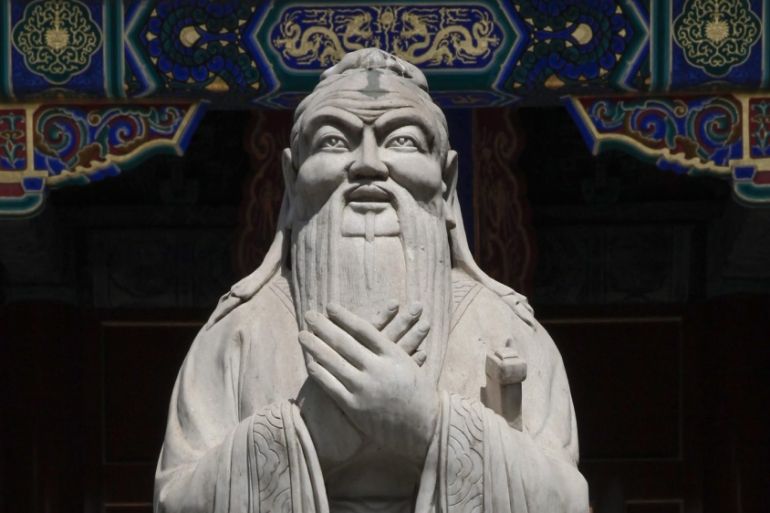

China’s new-found love for Confucius

Confucius is synonymous with Brand China, but can the Chinese government live up to the wisdom of Confucius?

Ask any educated person in the world to name one great Chinese thinker, and you’ll always get the same answer: Confucius. Ask that person to name a second Chinese thinker, and chances are you’ll draw a blank.

China is home to several of the world’s oldest and greatest philosophical traditions, but outside East Asia their key personalities are largely unknown. Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of the Qin dynasty, is known for his terracotta army and Sun Tzu for the ancient art of war. But the only Chinese philosopher who really registers for the rest of the world is Confucius.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsKing Charles unveils royal portrait

Cannes film festival hopes for ‘no controversies’ as wars, scandals rage

Energy summit seeks to curb cooking habits that kill millions every year

So it’s no wonder that when the Chinese government launched its soft power drive to spread Chinese language and culture around the world, it turned to the one figure who is the beginning and the end of Brand China: Confucius.

Brand China

|

|

China’s Confucius Institute is the biggest public diplomacy programme in the world. There are now more than 1,000 Confucius institutes and classrooms in 120 countries (and counting). Confucius institutes are major university-based teaching centres, while Confucius classrooms are smaller language learning support units for high schools.

Confucius also increasingly represents Brand China inside China itself. With 4,000 years of history to draw on, the Communist Party seems to have chosen Confucius to replace Mao as the country’s icon. Mao’s image may still appear on the currency, but these days Confucius dominates the school curriculum.

Long gone is the Little Red Book, the selection of Mao’s maxims that students once had to study and memorise. Now it’s the Analects of Confucius. Centuries ago, the mastery of Confucian thought was the key to passing imperial China’s famous civil service exams. Today schools are once again teaching a Confucian curriculum to the children of the elite.

OPINION: China’s Cultural Revolution must be confronted

For a brief time in 2011 there was even a statue of Confucius just off Tiananmen Square in the heart of Beijing; it was mysteriously removed and relocated to a less conspicuous location after just four months. There is tension between Maoist true believers and Confucius’ new acolytes. Confucius’s yellow star is rising, but Mao’s red star hasn’t fully set yet.

Mao was so vehemently anti-Confucius that after he died in 1976 it took nearly 30 years for Confucius to come out of hiding.

Down with Confucius

Modern China was not always so proud of its Confucian heritage. The Chinese Communist Party was born out of the May 4 Movement of 1919, a student protest movement dedicated to eradicating the traditional society of China’s imperial past. One of the main slogans of the May 4 protests was “Down with Confucius and Sons” – a demand for the end of patriarchy and the authoritarian government.

Communist China’s first leader, Mao Zedong, identified Confucius with the subjugation of women. He blamed Confucianism for promoting a conservative ideology of the family that prevented women from receiving an education and promoted the barbaric practice of foot binding, in which girls’ feet are tightly wrapped to stunt their growth.

Mao was so vehemently anti-Confucius that after he died in 1976 it took nearly 30 years for Confucius to come out of hiding. In 2005, Chinese President Hu Jintao unveiled his Confucian “harmonious society” slogan without mentioning the sage by name. It was left for Hu’s successor, Xi Jinping, to officially rehabilitate Confucius in a 2014 speech marking his 2,565th birthday.

OPINION: China’s misunderstood soft power

Confucius is now front and centre of Chinese political rhetoric, whatever the fate of his nine-metre tall statue. Mao’s portrait will certainly stay on Chinese currency until the centenary of the Communist Party in 2021, but we may witness a change shortly thereafter. Confucius is set to become the new face of official China.

Speaking truth to power

|

|

The name Confucius is a corruption of the Chinese name Kong Fuzi, which literally translates as Grand Master Kong. The Grand Master himself might be shocked to discover that he is revered as a fount of wisdom in 21st-century China. During his own lifetime he wandered from kingdom to kingdom, repeatedly exiled for condemning corruption and speaking truth to power.

At the foundation of Confucian thought are the three principles of ren (benevolence or love of humanity), li (propriety or proper behaviour), and yi (justice or righteousness). You might think that a philosophy based on benevolence, propriety, and justice would be a tough sell for a government that is extravagantly corrupt and firmly represses all dissent.

In fact many Chinese netizens do poke fun at the irony of Communist Party calls for Confucian harmony. In today’s China, “harmony” seems to mean not causing a disturbance by disagreeing with the government.

The Communist Party has embraced Confucius because he taught respect for authority – and the Party is in charge, at least for now. But the Confucian mirror image of respect for authority is the obligation owed by governors to the governed. Here the Communist Party of China increasingly falls short.

READ MORE: China’s ‘leftover’ women

Confucius was no democrat. But by all accounts he was a curmudgeonly critic of all of the governments of his day. It seems hard to believe that he would have approved of today’s Chinese government. If too many of its people actually go and read Confucius for themselves, the Chinese government may one day regret idolising the cantankerous Grand Master.

Salvatore Babones is a comparative sociologist at the University of Sydney. He is a specialist in global economic structure.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial policy.