How will the Republican candidates create jobs?

A closer look at the job plans of the Mitt Romney and Rick Santorum campaigns.

This is the second of a two-part article. The first part of this article, published here, analysed President Obama’s jobs plan. In the second part below, Paul Rosenberg turns to the jobs plans of former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney and former Pennsylvania senator Rick Santorum.

San Pedro, CA – We start with Romney, who released his jobs plan in September, getting a brief jump on President Obama’s employment speech to Congress. Despite its title, Romney’s plan is anything but tightly focused on job creation ideas. Quite the opposite, it rambles all over the map, while including 95 separate proposals. In unveiling it, Romney claimed his plan would produce 11.5 million jobs in his first term, with average GDP growth of four per cent per year, and a reduction in the unemployment rate from the then-current 9.1 per cent to 5.9 per cent.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia’s Putin eyes greater support from China for Ukraine war effort

India-Iran port deal: A gateway to Central Asia or a geostrategic headache?

India’s income inequality widens, should wealth be redistributed?

These claims seem dubious, at best. No Republican president since the Great Depression has presided over a four-year term with four per cent average growth. Only Democrats have done this well (or better) – and indeed, every Democrat except Jimmy Carter managed this level of growth for at least one term. Ronald Reagan’s second-term 3.7 per cent GDP growth – the best Republican record in this era – trailed Bill Clinton’s 4.4 per cent second-term growth, while George W Bush’s best – 2.2 per cent – was just half that of Clinton’s. While Johnson topped five per cent, Truman barely missed that mark and FDR topped 7.8 per cent his first term and just missed 15 per cent during World War II. There’s an old saying from the New Deal era: “If you want to live like a Republican, you must vote like a Democrat.” Three generations down the road, the historical record still bears this out.

Although Romney’s plan was touted as a “bold, sweeping and detailed proposal” promising a “fundamental turnaround of the American economy”, the pro-GOP Wall Street Journal said his plan “shrinks from some of the biggest issues”, and “strike[s] us as surprisingly timid and tactical considering our economic predicament”, while Politico noted: “Many of Romney’s proposed policies are standard GOP fare: cutting corporate taxes, reducing government spending, eliminating burdensome regulations, expanding US energy production and restricting the power of labour unions.” None of which have a particularly strong proven relationship with job creation.

What Politico called “standard GOP fare” generally means actions that favour GOP-aligned groups, regardless of economic impact. They help redistribute power and money upwards. Thus, Romney’s plan included these seven anti-labour provisions, none of which has any obvious job-creation role:

- (40) Appoint to the NLRB (National Labour Relations Board) experienced individuals with respect for the rule of law.

- (41) Amend NLRA (National Labour Relations Act) to explicitly protect the right of business owners to allocate their capital as they see fit.

- (42) Amend NLRA to guarantee the secret ballot in every union certification election.

- (43) Amend NLRA to guarantee that all pre-election campaigns last at least one month.

- (44) Support states in pursuing right-to-work laws.

- (45) Prohibit the use for political purposes of funds automatically deducted from worker paycheques.

- (46) Reverse executive orders issued by President Obama that tilt the playing field toward organised labour.

Similarly, Romney’s plan included a number of provisions to expand support for the fossil fuel industry (which, to be fair, Obama’s jobs panel also does), while concentrating support for green alternatives on “basic research” at a time when China, Europe and others are pouring production investments into these fundamental building blocks of the 21st century’s global economy. Besides favouring a dinosaur industry over a future-oriented one, fossil fuel production is notoriously capital-intensive, precisely the sort of spending that produces far fewer jobs per dollar than other uses of taxpayer money. How any such spending counts as a “jobs program” is a mystery indeed.

Despite the obstacles, there are two sensible ways to get a feel for Romney’s economic approach: first to look at the actions that he himself chose to highlight, and second, to look at his tax policies and spending policies – particularly regarding the big three – Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security, which in Romney’s case amounts to standard GOP fare (in order to get through the primaries) presented in a softer light (in order to not get massacred in the general election, should he get that far). On the first count, ABC News reported: “Romney says that, on the first day in office he would take ten actions to turn around the economy, including sending a package of five bills to Congress and asking for action within 30 days.”

Romney called that package of bills the “Day One, Job One Initiative”, clearly highlighting their importance, in his view. It included:

- Reducing the corporate income tax from 35 per cent to 25 per cent, which he claimed would induce short-term job growth through incentive hiring;

- Passing the “stalled” Colombia, Panama and South Korea Free Trade agreements;

- Calling for a survey of US energy reserves that could in turn promote domestic production of energy and create jobs;

- Making states responsible for retraining programs; and

- Submitting a bill to cut non-security discretionary spending by five per cent

It should be noted that the “stalled” free trade agreements were passed by Congress roughly one month later, and signed by President Obama almost immediately. Although conservative Republicans and neo-liberal Democrats such as Obama are both ideologically devoted to such agreements, the empirical evidence on them is decidedly mixed, at best. The economic theory of comparative advantage, which supports them, is a static theory, rather than a dynamic, developmental one, which deeply undermines its credibility, as explained by economist Ian Fletcher in his paper, “[Seven] Dubious Assumptions of the Theory of Comparative Advantage“. Empirically, the most prominent example, NAFTA, has made mainstream economists happy, but the results for workers have been much more negative, as documented in a 2006 report from the Economic Policy Institute: “Revisiting NAFTA: Still Not Working for North America’s Workers“. Thus, Obama’s support for these “free trade agreements” is strong evidence of how similar his views are to mainstream Republicans, rather than being wildly alien, as he is often portrayed.

Romney also promised to issue five executive orders to:

- Repeal “Obamacare”;

- Eliminate or repeal any Obama-era regulations that “have a negative effect on job creation and economic growth”;

- Develop a streamlined process to create new oil and gas drilling;

- Sanction China for currency manipulation; and

- Reverse pro-union orders issued by the Obama administration

Given that “Obamacare” is a federal law, Romney obviously can’t repeal it with an executive order. You’re supposed to learn this in high school civics class. Thus, Romney chose to give one of his top “job creation” slots to a political stunt to pander to the Republican base. Significantly, Romney’s plan only mumbled about Social Security and Medicare, which were briefly discussed, but did not appear on his summary list of his 59 points.

Under the heading “Enact Entitlement Reform”, which also did not make his list of 59 points, Romney framed his approach thusly: “First, we must keep the promises made to our current retirees: their Social Security and Medicare benefits should not be affected. But second, we should ensure that the promises that we make to younger generations are promises we can keep.” Since Romney ruled out raising more revenue, this clearly means cutting benefits. Regarding Medicare, he said: “The plan put forward by Congressman Paul Ryan makes important strides” but “as president, Romney’s own plan will differ, but it will share those objectives”.

Live Box 20121816112138306

Ryan’s plan would privatise Medicare through a voucher system that would only pay for a fraction of private medical insurance – a fraction that would continually decrease over time. Romney later said his plan would preserve the existing Medicare programme as an option, making it less punitive than Ryan’s plan, but also making it less economically coherent. In short, Romney plans deep cuts to government, but is reluctant to spell out the most painful details, much less consider how this will affect the economy and jobs.

Turning to Romney’s tax plan as a whole, an analysis from Citizens for Tax Justice found that Romney’s plan, cutting government revenues by $6.6tn, “would give the richest one per cent an average tax cut of $126,450, which would be over 100 times as large as the average tax cut of $1,220 that the middle fifth of Americans would receive”. However, this is largely based on inference, since Romney has only made a few sweeping statements, without releasing any detailed proposals. He’s also made some contradictory statements indicating he would cut top tax rates below what he previously stated.

Romney’s plan was actually the least expensive of all the GOP candidate plans that Citizens for Tax Justice analysed. Nevertheless, by continuing the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy, and adding even more tax cuts on top of them, Romney is clearly doubling down on the GOP’s trickle-down approach that has repeatedly failed to generate broad prosperity or even levels of overall growth that could compare with what Democratic presidents have previously delivered.

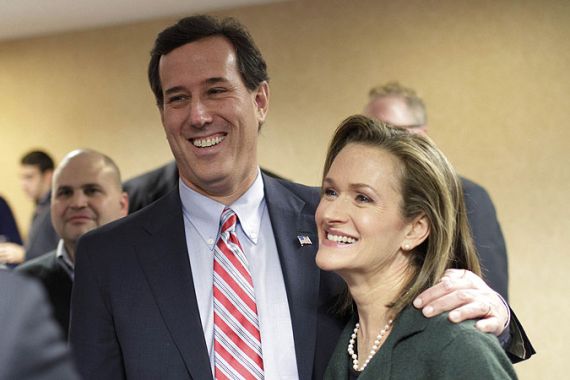

Rick Santorum’s jobs proposals

In November, Rick Santorum released his “Made In America” plan to “revitalise the American economy”. At least he did not misleadingly label it a “jobs plan” – although the jobs theme is implicitly underscored in the plan itself. Like Romney, its primary focus is broadly political – favouring one group over another rather than focussing on policies beneficial to the country and economy as a whole, but it’s presented somewhat less starkly in us-vs-them terms (more highlighting “us”, less focus on “them”).

Meanwhile, it adds one and a half dimensions that Romney’s plan lacks: It has a number of proposals favouring larger families (even with higher divorce rates, this tends to favour Republicans) and it also rhetorically targets rebuilding domestic manufacturing – even though it also includes provisions that favour overseas US companies as well. Rhetorically, Santorum does a superior job of melding economic and social conservatism, even though the empirical evidence relating this union to economic outcomes is far from compelling for most economists.

But there’s another problem with Santorum’s rhetoric and logic, as recently highlighted by BusinessWeek:

| “Republican presidential candidate Rick Santorum says he doesn’t believe the US government should pick the economy’s ‘winners and losers’. Except for manufacturers. And small businesses. And families.” This typifies the way in which the recent merging of social and economic conservatives – the culmination of a decades-long process – has increased political power at the price of basic, logical, realworld coherence.

In announcing his plan, Santorum said: “Our nation’s first economy is the family, and we must create an environment where families can thrive and succeed in America again. Government must get out of the way, and encourage an economic environment where the American entrepreneurial spirit can again take our nation to the heights of success. My plan does just that – it fosters families, gets the government out of the way, and rebuilds the great middle of America that has been lost over the past 50 years. It’s time that we focus on getting American[s] back to work.” |

It’s an appealing narrative to post-Bush conservatives, who would like to forget the massive deficits that Bush created, even before the economic meltdown – deficits that Rick Santorum, as a senator until 2006, had a big hand in creating. But this narrative is seriously at odds with the facts. The United States experienced manufacturing dominance and broad prosperity growth – higher for the middle class than for the top one per cent – during the early post-World War II period, which was dominated by big government liberalism. It’s the Reagan and post-Reagan period, from 1980 onward, when manufacturing has been exported, and middle-class incomes have stagnated, while the one per cent has prospered as never before. Economic deregulation – not big government – has dominated the period of the United States’ manufacturing decline.

Typifying this disconnect, the first point in Santorum’s plan is: “Cut and simplify personal income taxes by cutting the number of tax rates to just two – ten per cent and 28 per cent – returning to the Reagan era pro-growth top tax rate.” But, as already noted above, Reagan’s “pro-growth” record fell significantly short of Clinton’s, who got there by raising taxes – and eliminating the massive deficits that Reagan created.

Santorum also proposes cutting capital gains and dividend tax rates to 12 per cent, cutting the corporate income tax rate in half to 17.5 per cent and eliminating it entirely for manufacturers, also eliminating the inheritance tax and the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), tripling the personal deduction for each child, and increasing the research and development tax credit from 14 per cent to 20 per cent. All this is supposed to promote a US manufacturing renaissance. But Santorum would also reward US firms for their offshore businesses. He would eliminate the 35 per cent tax on repatriated overseas profits “when manufacturers invest in plant and equipment” and reduce it to 5.25 per cent on other repatriated income. In short, outside of manufacturing, US firms would be taxed at 17.5 per cent domestically, but 5.25 per cent for their overseas operations.

Regarding Santorum’s tax proposals as a whole, the Citizens for Tax Justice analysis found that his plan, totalling $9.4tn in cuts, would result in a similar disparity – albeit with the figures doubled – to Romney’s scheme. “[Santorum’s projections] would give the richest one per cent of Americans an average tax cut of $217,500, which would be over 100 times as large as the average tax cut of $2,160 that the middle fifth of Americans would receive.”

Like Romney, he would repeal “Obamacare”, saying he would replace it “with market-based healthcare innovation and competition to improve America and America’s health and create jobs”. But we already have a market-based healthcare system, which not only leaves tens of millions of us without medical care, it produces per capita costs roughly double those of the rest of the developed world. Santorum offers no explanation of how he would produce a different result.

Santorum’s target list for funding cuts includes the following proposals:

“Eliminate all agriculture and energy subsidies within four years, letting the markets work; eliminate resources for job killing radical regulatory approaches at the EPA and refocus its mission on safe and clean water and air and commonsense conservation; eliminate funding for Planned Parenthood and support adoption; reduce funding for the National Labour Relations Board (NLRB) for extreme positions undermining economic freedom; eliminate funding for implementation of Obamacare, and eliminate funding for United Nations organisations that undermine America’s interests.”

As with Romney’s plan, this is more about favouring Republican-oriented groups over Democratic ones than it is about job growth per se, with the notable exception of the very first item, which certainly deserves more attention than it’s gotten so far. Did Iowa farmers know about it, one wonders? Santorum would also “pass a Balanced Budget Amendment to the Constitution”, like Romney also promises – another power that the president does not have – while “capping government spending at 18 per cent of GDP”.

Santorum also promised to “reform Social Security and Medicare for sustainable retirements” – standard GOP boilerplate that’s virtually identical to Mitt Romney. But while Romney shied away from embracing Ryan’s draconian plan to destroy Medicare, starting in 2022, Santorum displays openly hostility that strongly suggests he’d like to begin dismantling Medicare immediately. “The Medicare system is simply like Romneycare in Massachusetts,” Santorum said on one occasion, “It is incredibly inefficient.” (In fact, as economist Paul Krugman notes, Medicare’s administrative costs of two per cent are far below private plans. Medicare Advantage plans average 11 per cent costs, and when profit-taking is added, this rises to 16 per cent the amount not going to actual medical care.)

“We should not have a government-run health care system on Medicare or anything else,” Santorum said on another occasion. He even once claimed that Medicare was “crushing” the “entire health care system in this country”. Santorum has yet to explain how doing away with Medicare is supposed to create jobs. The obvious answer – more money spent on advertising, administration and claims agents denying people coverage – is not exactly encouraging, since it also implies a reduction in actual medical care, and the jobs that go along with that.

Other points from Santorum’s plan include:

- Eliminate all other Obama era regulations with economic impact of more than $100m;

- Negotiate five Free Trade Agreements and submit to Congress in first year of presidency;

- Tap into vast US domestic energy resources to power our 21st century economy without picking winners and losers, so all American families and businesses can have lower energy costs;

- Unleash innovation in telecommunications and internet consumer options by getting government out of the way, which will expand productivity and lower costs;

- Block grant Medicaid, housing, job training and other social services to the States;

- Freeze current non-defence related federal worker pay levels for a year, and reduce federal workforce by at least ten per cent, with no compensatory increase in the contract workforce; and

- Reclaim the role of parents as the decision makers in their children’s education and incentivise the states to promote parental choice and quality educational options – because the family is the foundation of the economy.

At their best, it’s difficult to estimate any sort of job-creation impact for any of these measures. In part, this reflects the general GOP ideology that government can’t create jobs, it can only “create the climate” in which private businesses create jobs.

As can be seen by comparing this with Obama’s job plan, things look very different when you believe that government can play a direct, positive, measurable role. For one thing, the proposals get quite focused and specific. This facilitates analytical assessments, pro or con. For whatever combination of reasons, the so-called hard-headed “Daddy Party” no longer seems interested in that sort of thing.

Paul Rosenberg is the Senior Editor of Random Lengths News, a bi-weekly alternative community newspaper.

You can follow Paul on Twitter: @PaulHRosenberg