Judge sides with US slave descendants in Indigenous citizenship dispute

A judge with the Muscogee (Creek) Nation ruled an 1866 treaty offers path to citizenship for Black slave descendants.

In the United States, a judge for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation (MCN) has ruled in favour of citizenship for two descendants of Black slaves once owned by tribal members, potentially paving the way for hundreds of other descendants, known as freedmen.

Late on Wednesday, District Judge Denette Mouser, based in the tribe’s headquarters in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, sided with two Black Muscogee Nation freedmen, Rhonda Grayson and Jeff Kennedy, who sued the tribe’s citizenship board for denying their applications.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsClimate displacement threatens Indigenous Guna people in Panama: HRW

Could Indigenous communities in Brazil hold key to climate justice?

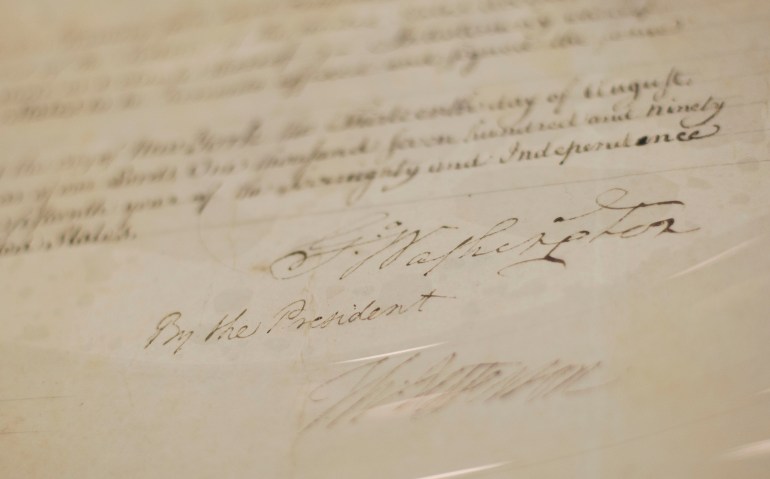

Mouser reversed the board’s decision and ordered it to reconsider the applications in accordance with the tribe’s Treaty of 1866, which provides that descendants of those listed on the Creek Freedmen Roll are eligible for tribal citizenship.

Freedman citizenship has been a difficult issue for tribes, as the US reckons with its history of racism. The Cherokee Nation has granted full citizenship to its freedmen, while other tribes, like the Muscogee Nation, have argued that sovereignty allows tribes to make their own decisions about who qualifies for citizenship.

Muscogee Nation Attorney General Geri Wisner said in a statement that the tribe plans to immediately appeal the ruling to the Muscogee Nation’s Supreme Court.

“We respect the authority of our court but strongly disagree with Judge Mouser’s deeply flawed reasoning in this matter,” Wisner said. “The MCN Constitution, which we are duty-bound to follow, makes no provisions for citizenship for non-Creek individuals. We look forward to addressing this matter before our Nation’s highest court.”

Tribal officials declined to comment further.

The Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek) and Seminole nations were referred to historically as the Five Civilized Tribes, or Five Tribes, by European settlers because they often assimilated into the settlers’ culture, adopting their style of dress and religion and even owning slaves.

Each tribe also has a unique history with freedmen, whose rights were ultimately spelled out in separate treaties with the US.

Mouser pointed out in her decision that slavery within the tribe did not always look like slavery in the US South and that slaves were often adopted into the owner’s clan, where they participated in cultural ceremonies and spoke the tribal language.

“The families later known as Creek Freedmen likewise walked the Trail of Tears alongside the tribal clans and fought to protect the new homeland upon arrival in Indian Territory,” Mouser wrote. “During that time, the Freedmen families played significant roles in tribal government including as tribal town leaders in the House of Kings and House of Warriors.”

The plaintiffs’ lawyer Damario Solomon-Simmons said the judge’s ruling has special meaning to him because one of his own ancestors, Cow-Tom, was among those who signed the Treaty of 1866 and ensured it included a provision guaranteeing citizenship for tribal members of African descent.

“It’s an amazing feeling to know we finally got a judge to look at the law and apply the law as written,” he said. “This is a victory against anti-Black racial discrimination, for the rule of law and for the sanctity of Indian treaties.”

Solomon-Simmons had argued that the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s constitution, which was adopted in 1979 and included a “by-blood” citizenship requirement, is in clear conflict with its Treaty of 1866, a point raised by Mouser in her order.

She noted the tribe has relied on portions of the treaty as evidence of the tribe’s intact reservation, upheld by the US Supreme Court in its historic ruling on tribal sovereignty in 2020’s McGirt v Oklahoma case.

“The Nation has urged in McGirt — and the US Supreme Court agreed — that the treaty is in fact intact and binding upon both the Nation and the United States, having never been abrogated in full or in part by Congress,” she wrote. “To now assert that Article II of the treaty does not apply to the Nation would be disingenuous.”