Hardeep Singh Nijjar killing: What does international law say?

If Canada proves allegations of Indian involvement, experts say killing would violate international, human rights law.

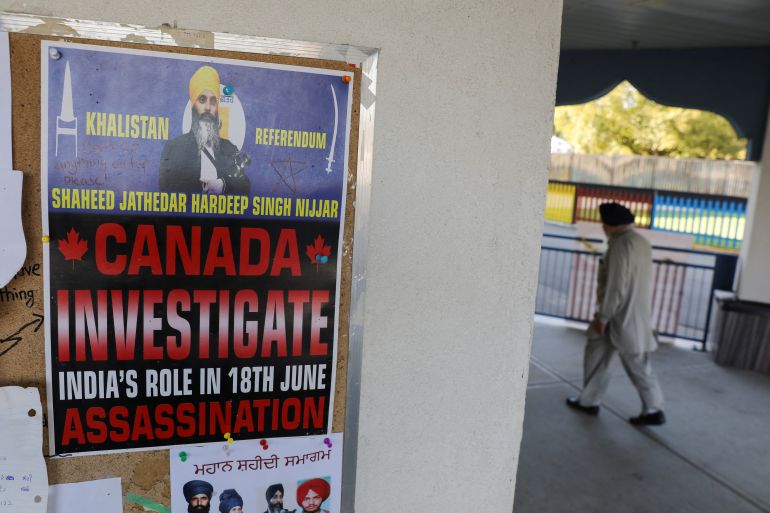

The fallout continues from Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s announcement that his government is investigating “credible allegations of a potential link” between the Indian government and the killing of a Sikh leader in British Columbia.

If those allegations are proven, experts said the June 18 killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar would represent a targeted, extrajudicial killing on foreign soil – and mark a flagrant violation of international law.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsIndia warns citizens on Canada travel amid row over Sikh leader’s murder

Has India killed a Sikh activist in Canada?

“The way Canada chooses to deal with this will show how seriously it’s taking this matter,” Amanda Ghahremani, a Canadian international criminal lawyer, told Al Jazeera.

India has roundly rejected any involvement in the deadly shooting outside a Sikh temple in Surrey, calling Trudeau’s comments on the floor of the Canadian Parliament on Monday “absurd” and politically motivated.

New Delhi also accused Ottawa of failing to prevent Sikh “extremism”, as the Indian authorities previously had designated Nijjar – a prominent leader who supported the creation of an independent Sikh state in India – as a “terrorist”.

Canada has faced calls to release evidence to back up its claims. On Thursday, Trudeau dodged reporters’ questions on the matter, saying his government was “unequivocal around the importance of the rule of law and unequivocal about the importance of protecting Canadians”.

India has for years accused Canada of harbouring “extremist” supporters of the so-called Khalistan movement, which seeks an independent homeland for Sikhs in the modern Indian state of Punjab.

While observers say the movement largely reached its peak in the 1980s, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government and its backers have regularly framed Sikh separatism as a pressing matter of national security.

International law experts told Al Jazeera the information that emerges in the coming days could be key to revealing the nature of the possible links between India and Nijjar’s killing. It could also show whether Canada intends to seek recourse, and if so, how.

Ghahremani said the Canadian government’s approach will depend on “what kind of message it wants to send out, not just to India, but any other country who is thinking of potentially committing this type of act in Canada”.

What international law violations could have been committed?

In the House of Commons on Monday, Trudeau stressed that any killing on Canadian soil under the auspices of a foreign government would represent a violation of the country’s sovereignty.

Marko Milanovic, a professor of public international law at the University of Reading in the United Kingdom, explained that this violation of sovereignty allegation – if proven true – would constitute a breach of what is known as “customary international law”.

According to Cornell Law School, that term refers to “international obligations arising from established international practice”, rather than from treaties.

“Essentially, one state is not allowed to send its agents onto the territory of another state without that government’s permission,” Milanovic told Al Jazeera. “Whatever they might do – they can’t go and do gardening, but they also can’t go and commit murder.”

Ghahremani added that if India was involved, the killing would violate the UN Charter, which states that “all members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state”.

She also explained that while international law outlines “the responsibility of states to other states”, an international human rights system “entails responsibilities to individuals”. For example, both Canada and India are parties to the International Covenant for Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), a treaty that enshrines the “right to life”.

That means such a killing “is not just a violation of international law, it’s also a violation of international human rights law”, said Ghahremani. However, she added that in the past, countries have cited self-defence as a justification for killing individuals on foreign soil.

That was seen after the administration of US President Donald Trump conducted a drone assassination of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani in Iraq in 2020, as well as when former President Barack Obama’s administration killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan in 2011.

Ghahremani said the situation in Canada would constitute “such an egregious example of violating state sovereignty – killing someone without any type of judicial process on the territory of another state – that it’s hard for me to think of a possible defence”.

“I think the most likely situation is that India will deny involvement,” she said.

What recourse could Canada pursue internationally?

Canada has not definitively linked India to the killing or released any evidence to back up its decision to go public with the investigation into the suspected connection.

Citing government sources, Canada’s public broadcaster CBC reported on Thursday that the intelligence collected by the Canadian authorities in Nijjar’s case included communications involving Indian officials and Indian diplomats based in Canada.

The report said some of the intelligence came from an unnamed ally in the so-called “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing alliance, made up of Canada, the United States, Australia, the UK and New Zealand.

Depending on how far Trudeau and his government are planning to push the issue – and if more definitive evidence emerges – they could eventually pursue a case in the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the UN’s main judicial organ, said Milanovic.

“However, both Canada and India made declarations, basically, under the statute to the court saying that the court will not have jurisdiction regarding disputes between Commonwealth member nations,” he said.

“So even in principle, the only way that a case could go to the ICJ is if the Indian government consented to this, and they’re not going to consent to it.”

Canada could also seek to resolve its dispute with India in an international human rights forum if proper criteria are met, according to Ghahremani. “In this case, since the act is a breach of the ICCPR, it would likely be through the UN Human Rights Committee,” she said.

“It’s not a judicial case, so it wouldn’t be a court ruling, but it would be a process that would address the issue between the two states.”

Will it go that far?

Still, several steps would have to happen before a case might be adjudicated in an international court, both Ghahremani and Milanovic agreed.

Such an escalation would largely be dependent on the evidence that emerges, the political will of Ottawa, and New Delhi’s response, among other factors.

“We have to keep in mind that before even getting to a potential ICJ case, Canada could just engage bilaterally with India to ask for compensation or other reparations, such as a declaration of non-repetition,” Ghahremani told Al Jazeera.

Milanovic also noted that only a “very small fraction of international disputes go to a courtroom”, and instead conflict resolution processes – if pursued – are typically handled through direct talks and negotiations.

Information that emerges in the coming days – through both official and unofficial channels – will likely begin to indicate the path Canada plans to take, he said.

“If we get little to no further information about this, it will be reasonably clear that the Canadian government will just want to wait this out and to have the whole thing die a natural death,” he said.

But if more facts emerge, “that will be an indicator that the Canadian government really wants to press this further.”

Is there any other recourse available?

Depending on what evidence is made public, Ghahremani said there are also several domestic opportunities for recourse against India, the most basic of which would be pursuing criminal responsibility for those who directly committed the killing.

Canadian police have said they are looking for three suspects.

“[Canadian authorities] could also potentially go after the intellectual author if they can link that back to somebody, including someone in the Indian government, that may have made the order or that planned the attack,” she said.

Ghahremani added that Nijjar’s family could also likely pursue a civil case against India because the killing took place on Canadian soil; as a result, they would likely not be barred from doing so under a Canadian law that prevents victims of human rights abuses abroad from bringing “suits against foreign governments and foreign agents in Canada”.

Still, Ghahremani said she sees value in Canada pursuing the case in an international forum since that would set a legal precedent. “I think Canada would do itself a favour by taking a very strong stance here to prevent such conduct in the future by any other state,” she said.