After Golden Dawn’s demise, a dangerous new far right flourishes in Greece

Boosted by election success, far-right strands are organising. But experts say they don’t yet pose the same threat as Golden Dawn.

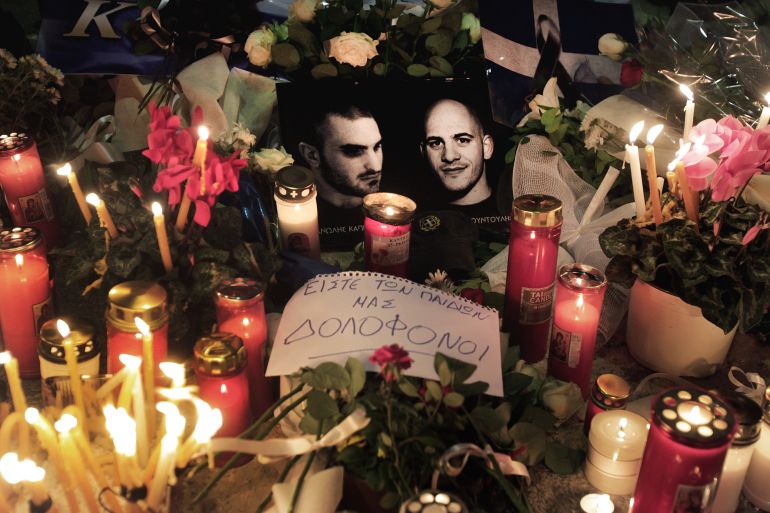

Athens, Greece – Far-right activists and neo-Nazi organisations in Greece recently called for a pan-European memorial in Athens, to commemorate 10 years since two members of the self-described Nazi organisation, Golden Dawn, were killed.

On November 1, 2013, Manolis Kapelonis and Giorgos Fountoulis – both in their 20s – were fatally shot in a drive-by attack outside the party’s office, an apparent revenge assault for the murder weeks earlier of the anti-fascist rapper, Pavlos Fyssas, by a Golden Dawn member.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsGerman blue-chips warn of ‘extremist’ threat before EU elections

Germany’s Scholz calls for unity against far-right after MEP seriously hurt

‘No turning back’: Carnation Revolution divides Portugal again, 50 years on

In response to this week’s call, dozens of antifascist groups organised counterprotests at nearby metro stations and squares.

A few days before these events, which were planned for Wednesday, the General Police Directorate of Attica issued a 24-hour ban on all public outdoor meetings.

The situation heated up on Tuesday night, when 21 members of the Italian neo-fascist group Casa Pound were arrested upon arrival at the Athens airport, and put in process for deportation.

On the appointed evening, a sense of chaos erupted in some parts of the Greek capital.

At two different metro stations in Athens, hundreds of antifascist demonstrators were held in static positions by rows of riot police.

At the small marble memorial for the Golden Dawn, supporters passed by rows of police, and left flowers or took selfies.

Later, anti-authoritarian protesters clashed with police at another metro station.

At the central Monastiraki metro station, a group of neo-Nazis attacked counterprotestors inside a cabin.

In videos posted online, far-right activists can be seen hitting people with belts and sheets of metal, and later dousing them in what appears to be petrol, threatening, “We will burn you alive.”

There were no fires, but several people were hospitalised with injuries.

Though Golden Dawn was officially deemed a criminal organisation in 2020, this week’s spectacle was evidence that the ideals and followers of Golden Dawn have not disappeared, and that the Greek far-right is reorganising.

“Clearly with the conviction of Golden Dawn, we didn’t finish with the far right in Greece,” Kostis Papaioannou, member of the monitoring network Point for the Study and Countering of the Far Right, told Al Jazeera.

“The main factors that feed the extreme right continue to exist and there is also a mainstreaming of the extreme right, of far-right ideas, both through the mainstream news and unfortunately by political parties.”

From political force to criminal organisation

In the 2000s, Golden Dawn was a central and potent force in Greek politics.

The party took on a populist appeal, positing that only their brand of fervent nationalism would assuage the country’s devastating economic woes.

They built up support in struggling neighbourhoods across Greece, and in 2012 won 7 percent of the seats in the Greek parliament.

During this period, the organisation bastioned their arguments with violence.

They regularly deployed members on nighttime patrols to beat and kill refugees and migrants – and sometimes left-wingers, often with impunity.

In 2013, Golden Dawn organised the coordinated murder of Fyssas, the popular anti-fascist rapper; several of the party higher-ups were later arrested.

In 2020, after years of trial proceedings, Golden Dawn was found guilty of several attacks on migrants and refugees, and trade unionists, as well as the murder of rapper Pavlos Fyssas.

After being criminalised, Golden Dawn was largely prohibited from engaging in political organising, but its former leaders have continued to campaign for political office from prison, members have shifted their support to other far-right organisations, and their violent methods have been glorified and parroted.

Ilias Kasidiaris, a Golden Dawn leader with a swastika tattoo who was jailed in 2021, founded the nationalist Hellenes party just before beginning his 13.5-year sentence at the Domokos prison.

The party was banned from this year’s parliamentary elections due to Kasidiaris’s criminal record.

But the 42-year-old, heavily active on YouTube and X, then endorsed the formerly unheard-of Spartans, and the party garnered a groundswell of support that won them 4.7 percent of the parliament.

The party’s leader, Vasilis Stigkas, has previous ties to Golden Dawn, and several other neo-Nazi organisations in Greece.

Two other far-right political parties also gained seats in this year’s elections – the ultranationalist Greek Solution and the Christian-conservative Victory.

In sum, these far-right parties now comprise 16 percent of parliament, making the current government Greece’s most far-right parliament since the fall of the military dictatorship in 1974.

Street violence

Outside of party politics, Golden Dawn’s use of street violence has also been replicated and mimicked.

In the middle of this year, as fires raged across Greece’s northern Evros region, a man broadcast on social media an extrajudicial kidnapping of refugees and migrants in Evros, whom he blamed for the fires. This video was shared by the leader of Greek Solution.

On August 12, a young Pakistani man, Sizar Saftar, was killed, in what the organisation the Movement United Against Racism and the Fascist Threat has identified as a racist murder, though it remains unclear who the perpetrators were.

In recent weeks, far-right youth groups around Athens have publicised their night patrols, during which they spray paint nationalist and racist slogans in various neighbourhoods.

Papaioannou said there has been an increase in street attacks recently.

“After the 2020 conviction of Golden Dawn, there was a decrease in the presence of this violence of racist neo-Nazi groups on the streets,” he said.

“However, there have been some appearances, around schools in the north of Greece and in Athens. And there is now a reactivation of these sorts of groups and violent attacks.”

Magda Skoutzou, head of a parents’ association in Athens, said “fascist” groups are “acting undisturbed”.

At the end of the previous school year here, she added, far-right activists stabbed two 15-year-olds in her neighbourhood.

Skoutzou stood with other parents and groups in the antifascist camp on November 1, and though they argued with police, were not allowed to go ahead with their demonstration.

“I believe it is my obligation to be here today,” said Skoutzou. “To emphasise that we do not want fascist groups to have any space in our neighbourhoods and schools.”

Experts of the Greek far right note that, despite their more visible presence, these attack groups are still not nearly as organised or as strong as they were during the heyday of Golden Dawn.

“The groups we have now – Propatria, or for example, the Youth Front of Golden Dawn, which is essentially a group in Thessaloniki – these are very small groups that try to recapture the threads of the old to do the same thing, but it doesn’t work now,” said Dimitris Psarras, a journalist who reported on Golden Dawn since its formation.

“They imitate [Golden Dawn] but have neither the power nor the appeal.”

Psarras said these neo-Nazi groups operate differently from the all-encompassing top-down approach of Golden Dawn.

“The groups that do far-right politics now, such as Velopoulos [Greek Solution] in the Parliament, or even the Spartans, on the surface, they want to appear that they are only political activists, they don’t do other actions,” he said.

“It’s like the Golden Dawn has split into the political and military branches that used to be together and now they’ve split, although there definitely remain among them connections and contacts.”