Australia’s early plans for ‘dangerous’ encryption law revealed

Documents show Canberra began seeking powers to crack encrypted communications nearly two years before unveiling law.

The Australian government began seeking controversial powers to crack encrypted communications almost two years before unveiling landmark anti-encryption legislation branded “dangerous” by tech industry leaders, newly obtained documents reveal.

Australia in 2018 passed world-first laws to force tech companies and service providers to build capabilities allowing law enforcement secret access to messages on platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook – such as push notifications that download malware to a target’s computer or phone.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIndian government helps central bank to circumvent inflation law

COVID-19: The endless search for the origins of the virus

Jackson’s US Supreme Court nomination moves forward in Senate

The legislation, which Canberra said was necessary to prevent “terrorists” and other serious criminals from hiding from the law, drew fierce opposition from privacy experts and tech industry players, who warned that undermining encryption could compromise the privacy and security of millions of people worldwide.

Previously unseen documents obtained by Al Jazeera under freedom of information laws show that Canberra’s push to get around encrypted communications, which are invisible to third parties, was in the works at least as far back as 2015.

Former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull unveiled legislation to tackle encrypted communications in July 2017, declaring the internet should not be used as “a dark place for bad people to hide their criminal activities from the law”.

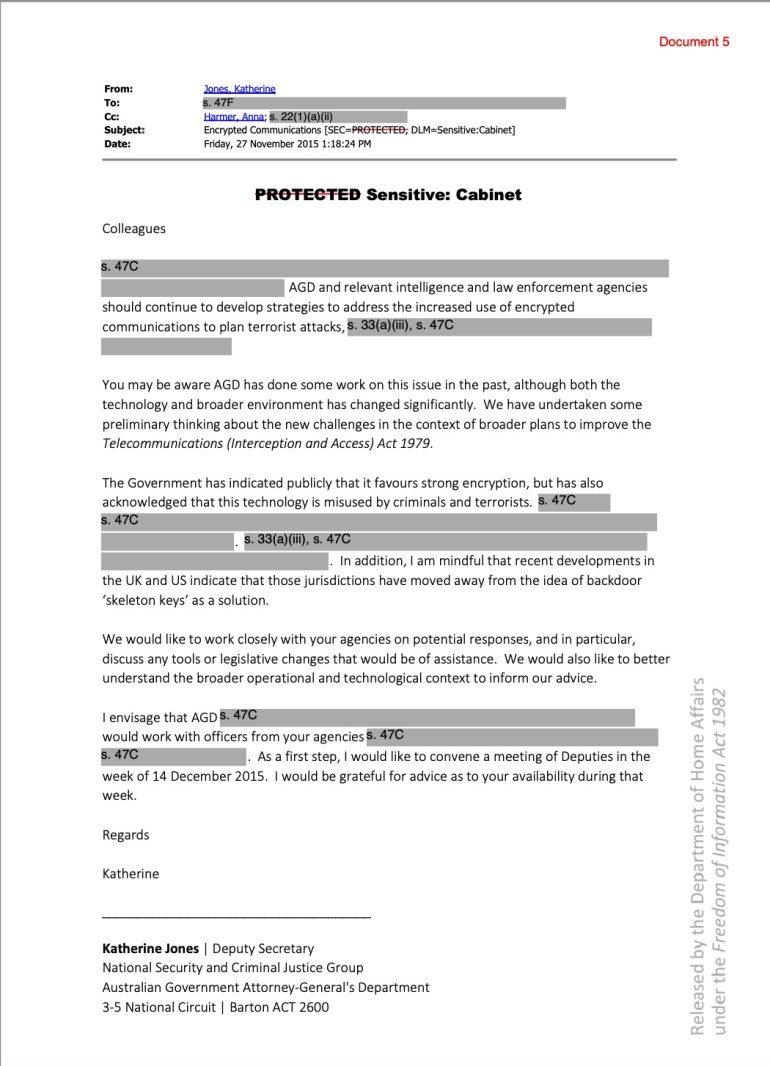

In a letter to government agency heads on November 27, 2015, Katherine Jones, a top national security official within the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD), outlined the need for her department and “relevant intelligence and law enforcement agencies” to “continue to develop strategies to address the increased use of encrypted communications to plan terrorist attacks …”.

“You may be aware AGD has done some work on this issue in the past, although both the technology and broader environment has changed significantly,” said Jones, the then-deputy secretary of the National Security and Criminal Justice Group within the AGD.

“We have undertaken some preliminary thinking about the new challenges in the context of broader plans to improve the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979. The Government has indicated publicly that it favours strong encryption, but has also acknowledged that this technology is misused by criminals and terrorists.”

The letter, which is partly redacted, also refers to the contentious issue of so-called “back doors,” which would become key in the government’s later messaging insisting the legislation would not threaten the general public’s privacy.

While the Turnbull government insisted the Assistance and Access Act would not create systemic vulnerabilities that could undermine encryption in general, tech giants Google, Facebook, Twitter and Apple lobbied against the legislation, with the latter at the time describing it as “extraordinarily broad” and “dangerously ambitious”.

“In addition, I am mindful that recent developments in the UK and US indicate that those jurisdictions have moved away from the idea of backdoor ‘skeleton keys’ as a solution,” Jones wrote in the letter.

“We would like to work closely with your agencies on potential responses, and in particular, discuss any tools or legislative changes that would be of assistance. We would also like to better understand the broader operational and technological context to inform our advice.”

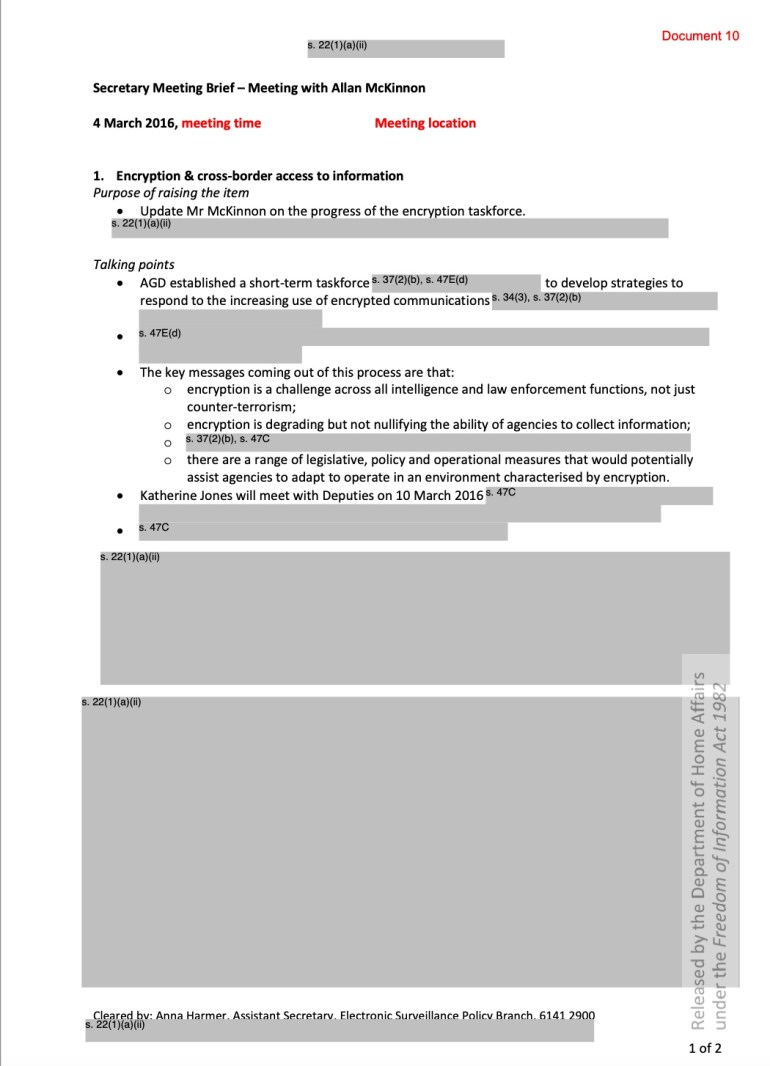

In March 2016, encryption and “cross-border access to information” were included on the agenda of a meeting between Allan McKinnon, the then deputy secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, and unnamed officials, according to a heavily redacted briefing document.

The briefing describes encryption as “degrading but not nullifying” law enforcement’s intelligence-gathering abilities and refers to a “range of legislative, policy and operational measures that would potentially assist agencies to adapt to operate in an environment characterised by encryption”.

Justin Warren, chair of Electronic Frontiers Australia (EFA), told Al Jazeera the language of the briefing did not match governments’ public rhetoric about the threat posed by encryption.

“The public rhetoric implies that encryption is somehow fundamentally damaging, as if authorities had no other powers or abilities, which isn’t remotely true,” Warren said.

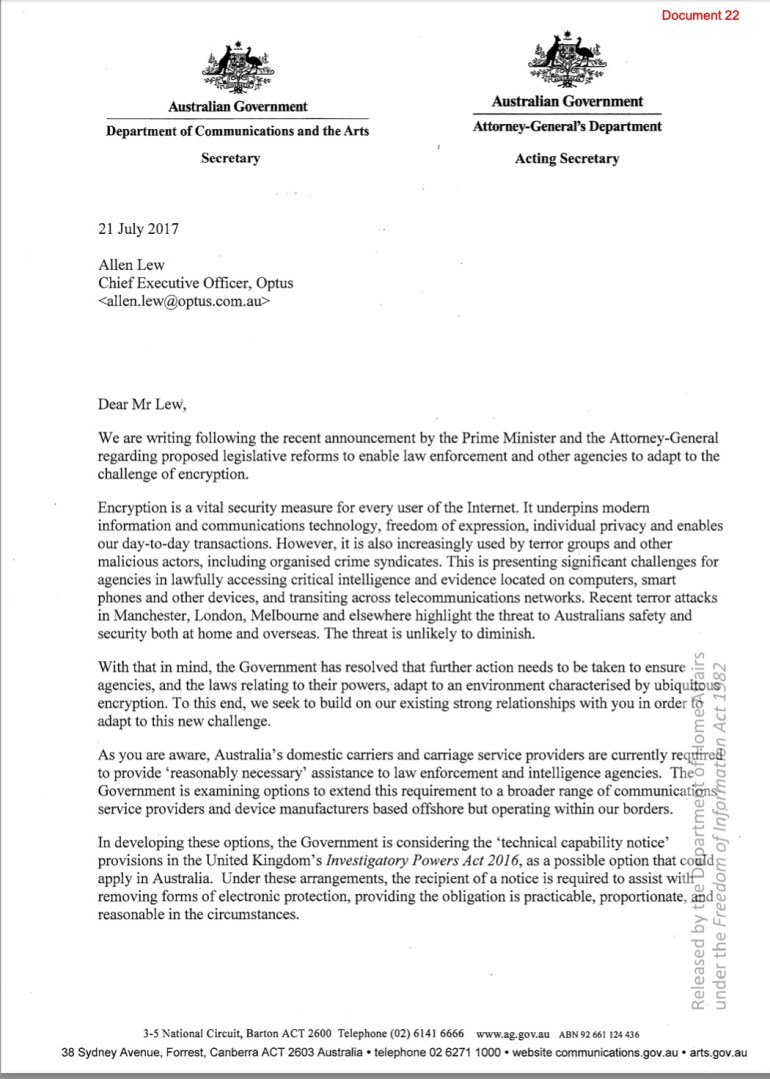

The documents obtained by Al Jazeera also shine a light on the government’s consultations with telecommunications firms following Turnbull’s announcement of the legislation in 2017.

In letters sent that July, Jones and Heather Smith, the then-secretary of the Department of Communications and the Arts, invited the CEOs of local players Optus, Vodafone Australia, TPG and Telstra to a meeting to discuss the proposals.

“We emphasise that the government will not require the creation of so-called ‘back doors’ to encryption – this is, requiring that inherent weakness by built into encryption technology,” the letter said. “Rather, the government is seeking collaboration with, and reasonable assistance from, our industry partners in the pursuit of public safety.”

Al Jazeera obtained the documents, which also include a comparison of legal frameworks around encryption in different Western countries, nearly five years after submitting a freedom of information request for information about Australia’s planned anti-encryption regime.

After several denials to the requested information by the AGD, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner in February ruled the government should release some, but not all, of the materials identified in the request.

EFA’s Warren said it was concerning that basic information about the government’s plans took so long to be released to the public.

“It would have been useful to have this information while the debate into the Assistance and Access Act was happening, a key objective of the FOI Act,” he said.

“The lengthy delay has damaged Australia’s ability to have a well-informed debate in a timely fashion. This is an issue across the board: the Australian government is working hard to keep its own activities secret while it simultaneously damages our privacy.”

The AGD referred a request for comment to the Department of Home Affairs, which took over some of the AGD’s responsibilities following the passage of the law. The Department of Home Affairs has been contacted for comment.