Indian government helps central bank to circumvent inflation law

India’s finance ministry let RBI escape accountability for missing the inflation target in 2020.

New Delhi, India – The Indian government did not apply the law when the country’s central bank breached the 2020 inflation target, documents accessed by The Reporters’ Collective (TRC) and Al Jazeera through the Right to Information Act show.

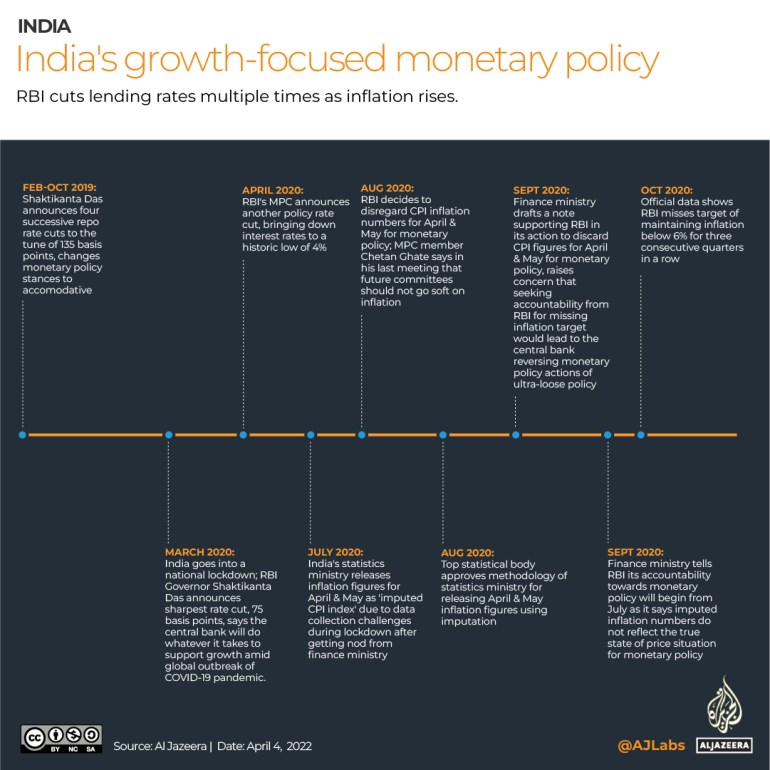

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), under Governor Shaktikanta Das, was unable to keep inflation within the legally mandated limit of 6 percent for the three consecutive quarters between January and September 2020.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAs Omicron looms, India’s central bank holds rates

Looming Fed rate hikes have emerging markets dreading deja vu

Long after lockdowns, India’s youth still struggle to find work

Under Indian law, if the RBI fails to meet the inflation target for three consecutive quarters, it is required to write to the government within one month explaining why and produce a plan to bring prices back in line. This transparency is required to prevent businesses and citizens from losing faith in the RBI and the government’s ability to rein in inflation.

However, the Ministry of Finance, with finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s approval, gave the central bank a pass, documents show.

It suggested the official inflation figures for the specific period had been estimated under constraints of a pandemic-induced lockdown, and hence were not reliable enough to be used for setting the interest rate, the ministry informed the RBI.

But, records show, these numbers had been endorsed at all levels of the government and its statistical agencies and had been used by the government for all other economic assessments.

What the finance ministry was worried about, as internal documents showed, was that the central bank would start hiking interest rates to control price rises at a time when the administration favoured lower borrowing costs to revive the economy.

The finance ministry and RBI did not respond to a list of detailed questions sent by Al Jazeera.

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi put India into one of the world’s strictest lockdowns in 2020 to curb the spread of the coronavirus, inflation shot up on the back of supply shocks. In the process, the central bank missed its inflation target, a first since an independent monetary policy committee (MPC) under the RBI governor was set up in 2016. The MPC was tasked with keeping the inflation levels in check (see Part 1) by setting the interest rates at which it lends money to banks.

The process

Under the law, the RBI is required to maintain the consumer price inflation at 4 percent – but has some wiggle room with upper and lower limits of 6 percent and 2 percent. If inflation breaches this band for three consecutive quarters, it is legally considered RBI’s “failure”. Lower interest rates lead to more money in the economy, which in turn leads to inflationary pressures. The central bank reigns in inflation by adjusting the interest rate.

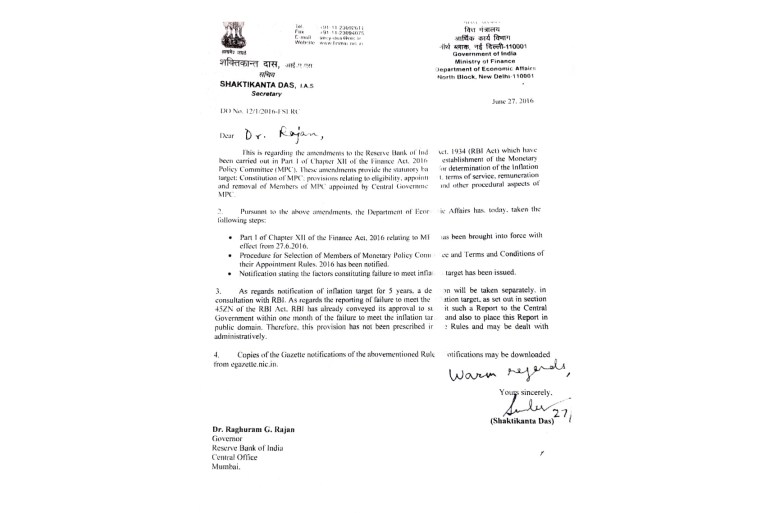

While framing the rules for the monetary policy framework in 2016, the RBI’s present governor, Das, who was the economic affairs secretary at the time, received a commitment from the RBI on the one-month deadline, according to the documents reviewed by TRC and Al Jazeera. The RBI was also in favour of making the accountability report public, according to communication between the RBI and the finance ministry in 2016.

“RBI has already conveyed its approval to submit such a[n accountability] report to the Central government within one month of the failure to meet the inflation target and also to place this report in public domain. Therefore, this provision has not been prescribed in the rules and may be dealt with administratively,” Das wrote in a letter to then RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan on June 27, 2016.

Central banks in Indonesia, the Philippines, Brazil, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Norway, and Turkey, among others, follow this practice of writing an open letter addressed to the government as a part of the accountability mechanism.

Post-COVID monetary policy

India’s inflation had started moving above the RBI’s target even before the March 2020 lockdown. The Consumer Price Index rose from 5.8 percent in October-December 2019 to 6.7 percent in January-March 2020, on average.

Within days of going into a nationwide lockdown, the RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC), following in the footsteps of its global peers, sharply cut the repo rate – the rate at which banks borrow from the RBI – by 75 basis points to 4.4 percent in March. Another cut followed in May, taking the rate to a record low of 4 percent.

Around the same time, central banks of several emerging economies including Brazil, Mexico and South Africa, cut rates by more than 200 basis points to revive growth.

Their average rates of inflation in 2020 remained mostly at pre-pandemic levels and, more importantly, within their respective central banks’ targets.

But in India, inflation remained high at 6.6 percent in April-June 2020, before rising even higher to 6.9 percent in July-September. Taken together with the January-March quarter of 6.7 percent, inflation would have breached the legal mandate of staying within 6 percent for three consecutive quarters.

The MPC when it met in August was aware that it was on the verge of breaching its legal mandate. In the meeting RBI deputy governor Michael Patra acknowledged inflation had risen “above the upper tolerance band”.

But the MPC decided to disregard the data for April through June, arguing that the statistics ministry had estimated those numbers through a different methodology called imputation.

Building a case

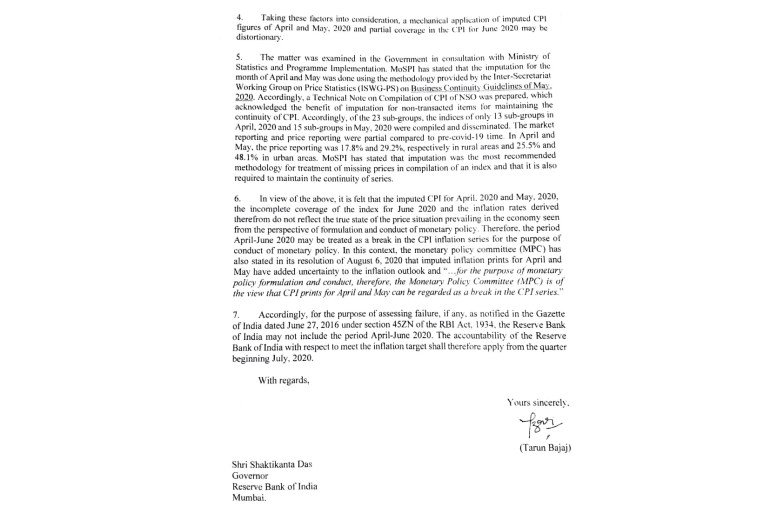

In September, the finance ministry in an internal note, titled “Note on consequences of failure to achieve inflation target under Monetary Policy Framework”, defended the RBI’s actions and said because of the process of imputation, the inflation estimates were “artificially” overstated and were “unrealistic”.

The government feared the central bank would start hiking interest rates to control inflation, which would lead to high borrowing costs for businesses when the economy was already in the doldrums. By discarding the April and May data, the RBI had more room to adopt an accommodative stance that left it open to interest rate cuts down the track.

In the same note, the finance ministry said an “unqualified application” of the imputed CPI data to set monetary policy “should be avoided” as that “might lead to counter-intuitive and counterproductive measures of monetary tightening on the part of RBI when the macroeconomic situation is weak and this would result in distortionary and chaotic outcomes.”

In parallel, the finance ministry sought the statistics ministry’s views on its decision to discard the inflation numbers. The statistics ministry stood by its estimates and reminded the finance ministry that it had released the inflation numbers after the latter’s approval. The inflation estimates for the two months also had the nod of the government’s expert statistical body, the Technical Advisory Committee of Statistics of Prices and Cost of Living.

Other experts were also pointing to the high prices hitting citizens.

In its July 2020 research report, India’s largest bank, the State Bank of India (SBI), in its own estimates, found that retail inflation in India was much higher in the April-June quarter than official estimates. Its calculations showed CPI inflation at 9.68 percent, instead of the official figure of 7.22 percent in April and 7.82 percent rather than the official estimates of 6.27 percent in May.

But both the finance ministry and the RBI decided to discard the April-June quarter inflation data for the purpose of setting interest rates.

With the approval of finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, then-Economic Affairs Secretary Tarun Bajaj, who is now the revenue secretary, wrote to RBI governor Das in September saying that the inflation figures for April-June, 2020 “do not reflect the true state of the price situation prevailing in the economy seen from the perspective of formulation and conduct of monetary policy”.

Bajaj also said the “accountability” for the inflation target “shall therefore apply from the quarter beginning July 2020”.

RBI had been given a pass. The accountability measure had been junked.

Lack of transparency

When the RBI released its half-year monetary policy report in October 2020, part of its regular transparency efforts, it did not mention the leeway it got from the government.

In February 2021 the RBI published a report titled Reviewing the Monetary Policy Framework. In a chapter on accountability, it said: “Since the adoption of FIT (flexible inflation target), between October 2016 and March 2020 there has been no failure by the MPC, as per this definition.” The report left out MPC’s track record for the controversial April quarter of 2020.

Other central banks, despite facing data issues of a similar kind, chose to follow their accountability mandate. After the UK’s Bank of England missed its inflation target in May 2020, it wrote an open letter to the UK government explaining the reasons why, which included problems with data collection.

Indian Statistical Institute professor Chetan Ghate, an MPC member from 2016 to 2020, in an interview with the Informist news agency in August 2021, said the MPC’s credibility would have been enhanced had it accepted that it had failed to manage inflation.

“So, in a pandemic year, amid a once-in-a-century event, if the committee hadn’t met its target because it felt growth concerns needed priority, perhaps the MPC may have actually gained credibility had it admitted that it was not able to meet its inflation target given the need to focus on growth,” Ghate said.

Williem Buiter, adjunct professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University and former external member of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee, who has been invited by the RBI to deliver lectures in the past, said that the Indian central bank should not have been “too ashamed of” missing the inflation target “by a small margin” in 2020.

“The RBI should not have been given a waiver from having to write an open letter to the government explaining about the causes of failure, remedial measures and the timeline within which consumer price inflation will come back to the target of 4 percent,” Buiter said in an email. “They should have written the letter, pointing to the exceptional circumstances that prevailed from March 2020, and arguing that this technical ‘“failure’” was in fact a modest success,” he said

RBI, on the other hand, was now looking for even greater flexibility going forward, this time through a change in the regulations. Its February 2021 report called for easing the definition of “failure” in meeting the inflation target and said the government should increase the period for maintaining inflation levels between 2 and 6 percent to four consecutive quarters rather than the current three.

The concluding part of the series will be out tomorrow.

Somesh Jha is a member of The Reporters’ Collective.