Polish Muslims bury Syrian, 19, who drowned near Belarus border

Ahmad al-Hasan’s body was found in the Bug River in eastern Poland after he drowned while trying to cross over from Belarus.

Bohoniki, Poland – His name was Ahmad al-Hasan and he was 19. He wanted to continue his education, which he began in a Syrian refugee camp in Jordan.

But his dreams will never come true.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsPoland slammed for ‘arbitrary’ ban on media at Belarus border

Syrian asylum seeker found dead on Poland-Belarus border

On October 19, his body was found in the Bug river in eastern Poland, close to the Belarus border.

According to his companion who survived, al-Hasan was pushed to enter the water by a Belarusian guard. He could not swim.

On Monday evening, he was laid to rest in a grave at a Muslim cemetery in Bohoniki, a few kilometres away from the Belarus border, as his family members in Jordan and Turkey watched the ceremony via video-link.

The imam did not perform traditional ablutions. After a month in a morgue in Poland, al-Hasan’s remains were too decomposed.

Reciting prayers, Imam Aleksander Bazarewicz’s voice resounded far into the dark, gloomy woodlands. Dozens surrounded the grave to pay the last respects.

“This is not the end. Death is not a tragedy, it only means that God has a better place for him. He died a tragic death, he drowned so he has a status of a shahid, of a martyr,” the imam said.

Three Muslims present, like al-Hasan, were refugees who came to Poland seeking a better life. Two were members of the local Tatar community.

Kasim Shady, a doctor from Syria who has made Poland his home, broadcast the ceremony on his phone to al-Hasan’s relatives.

“May he rest in peace,” Shady said. “I am a refugee too and I managed to build my life here. I am a doctor. But many people didn’t manage to escape. We are happy that our brothers agreed to bury him here. We wanted more people to come, but not everyone could join us.”

At least 11 people have been reported to have died at the Polish-Belarus border in recent weeks.

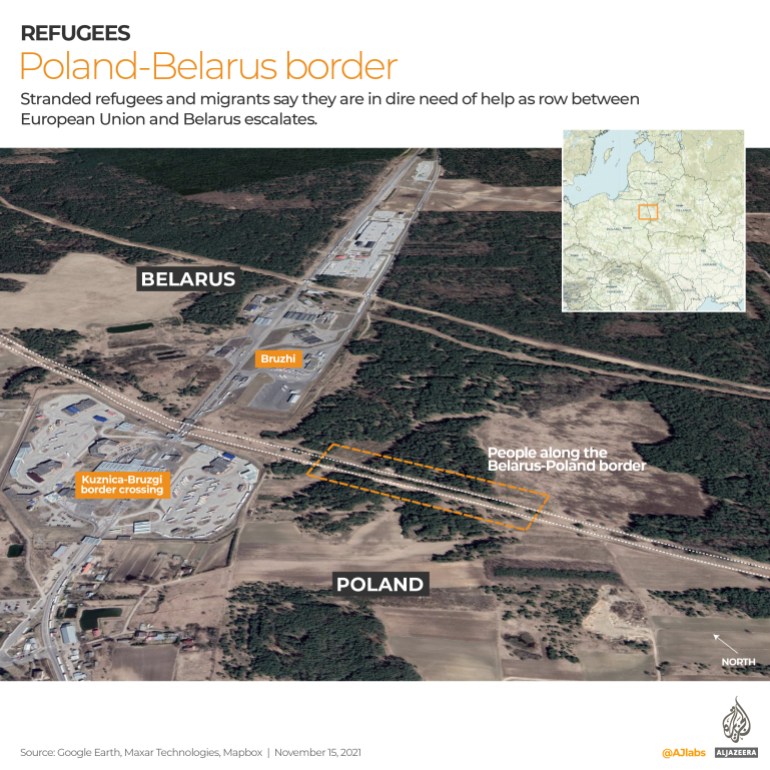

The crisis began in August and since then, thousands of refugees have tried to enter Polish territory, the eastern frontier of the European Union.

Those who managed to breach the frontier spent weeks in the woodlands in the borderland, allegedly facing pushbacks to the Belarusian side by the Polish guards.

The international community has held Belarus responsible for the deteriorating situation, claiming that Minsk is trying to destabilise Europe.

Earlier this year, Belarus removed visas for citizens of a number of Middle Eastern and African states and opened numerous tourist agencies offering an easy and cheap way to get to Europe.

Critics have said the move might be an act of revenge against Poland, which supported last year’s protests against longtime President Alexander Lukashenko.

While many of the tourist agencies have been forced to close down, and as countries such as Turkey now refuse to let citizens of Iraq, Yemen and Syria, on Belarus-bound planes, the chaos is far from over.

On Tuesday, clashes broke out at the border between Polish guards and refugees, and aid workers have warned of a looming humanitarian disaster.

Polish authorities have delineated an emergency zone at the border with Belarus, which no one, including journalists and NGOs, is allowed to enter.

As a result, the hundreds of refugees who manage to cross into Poland become stranded in the woods, with no access to humanitarian assistance, food and water.

For the local Muslims of Bohoniki, the crisis at the border is a test.

Tatars have lived in the Polish-Belarus borderland for centuries.

They were invited to the territory in the second half of the 17th century by John III Sobieski, king of Poland and grand duke of Lithuania, to help his army defend the kingdom.

Ever since, Bohoniki and Kruszyniany, two villages close to the Belarus border have been the centre of Islam in Poland.

Tatars loyally served the king and consecutive governments and fought for Poland in the 20th-century wars.

In 1919, they organised their own regiment, fighting alongside the Polish army and proudly bearing a Muslim crescent on their uniforms.

But the descendants of Tatar defenders of Polish borders are reluctant to accept the current narrative and actions of the Polish government.

For them, people looking for shelter at the Polish-Belarus border are not a threat. They are people, brothers in faith, whose lives are being lost.

“We should give them water and food. They are not a threat. They are afraid of us, they don’t know how people will act when they see them. I feel so sorry for them, for the children, the little children. People are warm at home and these people are outside, in one piece of clothing, it’s incredible how they survive,” said Ali, a Muslim Tatar.

“I feel bad. Once, [Jarosław] Kaczynski (leader of the governing Law and Justice (PiS) party) said that Poland is for Poles and Catholics. It breaks my heart. There are also Orthodox Christians here and Muslims, Tatars, so how can someone say that?”

Officially, the Muslim community does not criticise the government’s actions.

But local Muslims, together with activists across the country, have been involved in gathering sleeping bags and warm clothes for refugees scattered across the Polish woodlands.

After the funeral, a small mound covered al-Hasan’s grave.

Imam Bazarewicz put a large pine tree branch on top. Activists left a red lamp next to it, the same type of light they use while floundering the forests looking for people in need.

“There is no good in this world. But we cannot give up. We have to support people, we have to feed them,” said Eugenia, 75, a local Muslim Tatar. “I’ve never thought something like that would be possible.”