How Egypt’s referendum deepened its human rights crisis

Rights groups say Egypt’s constitutional amendments consolidate executive control of judiciary, placing army above law.

As protests spread across the Arab world in 2011, Egypt became a beacon of hope in the region.

But this glimmer of light quickly dimmed, rights groups say, pointing to a widespread crackdown on dissent, with recent constitutional amendments only deepening the country’s human rights woes.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsIs the ICC going to issue arrest warrants for Israel and Hamas leaders?

Russian playwright and director go on trial over ‘justifying terrorism’

UK court to rule on Julian Assange extradition appeal: What could happen?

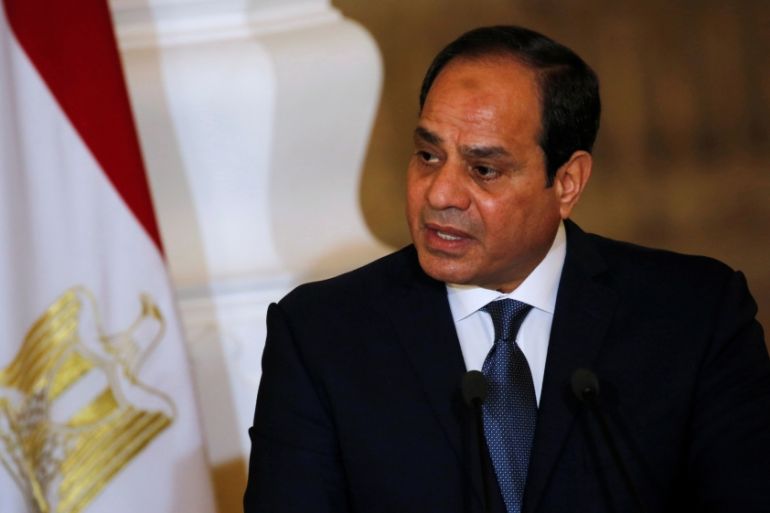

In 2013, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the then-defence minister who overthrew the country’s first elected president in a coup, promised to keep to the two four-year terms mandated by the Egyptian constitution.

But on Tuesday, electoral authorities announced that the amendments had been approved in a national referendum – with a 44 percent turnout – allowing President el-Sisi to extend his current four-year term to six years and run for another six-year term in 2024.

The amendments also bolster the role of the military and expand the president’s power over judicial appointments, further raising analysts’ concerns over the country’s judicial independence and human rights situation.

“The human rights trajectory in Egypt has been in a deep descent for several years now. The litany of serious abuses during President el-Sisi’s rule … appears set to continue with the constitutional amendments enshrining long-term autocratic rule,” Michael Page, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch (HRW), told Al Jazeera.

“What’s especially concerning in these now-approved amendments is how they further undercut what’s left of the concept of an independent judiciary in Egypt, as well as how the amendments grant further licence for Egypt’s military to intervene in civilian affairs,” he added.

![Egyptians overwhelmingly backed constitutional changes allowing el-Sisi to extend his current four-year term to six years [File: Mohamed Abd El Ghany/Reuters]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/e5cc887fdbc34b4ab9c213fa3ebddf4c_19.jpeg)

‘Subordinated judiciary, stronger military’

Under amended constitutional articles 185, 189 and 193, the president will have the authority to appoint the heads of judicial bodies and authorities, select the chief justice of the Supreme Constitutional Court, and appoint the public prosecutor.

At the same time, amended article 200 vastly expands the power of the military, giving it the duty to “protect the constitution and democracy, and safeguard the basic components of the State and its civilian nature, and the people’s gains, and individual rights and freedom”.

Said Benarbia, Middle East and North Africa director of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), said the amendments enshrined executive control of the judiciary and interference in judicial matters while placing the military above the law and constitution.

“Egypt’s military and executive have subordinated the judiciary and the office of the general prosecutor to their political will, making them a docile tool in their ongoing, sustained crackdown on human rights in the country,” Benarbia told Al Jazeera.

According to Benarbia, the amendments run contrary to international standards on judicial independence and undermine Egyptians’ basic rights.

“The amendments will undermine Egyptians’ right to take part in the conduct of public affairs, including to freely determine their political status and to choose the form of their constitution or government free from any interference by, or subordination to the military,” explained Benarbia.

Benarbia added that these amendments “will also undermine Egyptians’ right to a fair trial before a competent, independent and impartial court of tribunal.”

Lead-up to the vote

Concerns among observers had heightened in the weeks leading up to the referendum, as a campaign of intimidation, ongoing mass arrests and a deepening crackdown on fundamental freedoms by the Egyptian authorities attempted to silence any opposition.

According to a Human Rights Watch report published ahead of the vote, mass arrests and smear campaigns targeted activists who called for boycotting the referendum or rejecting the amendments, including members of a coalition of 10 secular and leftist political parties, several activists and famous actors.

According to local newspapers, opposition figure and former presidential candidate Hamdeen Sabahi was under investigation by the authorities for “instigating chaos” over his opposition to the amendments.

Meanwhile, award-winning actors Amr Waked and Khaled Abol Naga, both of whom are based abroad, were expelled from the Egyptian actors’ union. Egyptian authorities are also investigating them over accusations of treason after they spoke out against el-Sisi.

According to HRW, 160 dissidents were arrested or prosecuted in Egypt during February and March alone. The authorities blocked independent campaign website, Batel – which translates into “void” – ahead of the referendum, along with seven other alternative websites that campaigned against the amendments, said the report.

The referendum itself, therefore, took place amid “widespread suppression of fundamental freedoms, including freedoms of expression, association, and assembly and the right to political participation,” said HRW in its report.

Years of suppression

During el-Sisi’s time as defence minister, security forces embarked on a nationwide crackdown that began with the killing of around 1,000 protesters as they cleared Muslim Brotherhood sit-ins in Cairo in August 2013.

Following el-Sisi’s election as president in 2014, the government “committed widespread and systematic human rights violations, including mass killings of protesters, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, extrajudicial killings of detainees, and torture and other ill-treatment in detention,” according to HRW.

Dalia Fahmy, associate professor of political science at Long Island University, told Al Jazeera: “Hundreds of political activists and protesters have reportedly been arrested for unauthorized protests or for criticizing the president online. Mass unfair trials… sweeping death sentences and using death sentences to settle scores… have further tightened the noose.”

“The youth that Amnesty International once referred to as ‘Generation Protest’ is now ‘Generation Jail’.”

Although the crackdown initially targeted el-Sisi’s Islamist opponents, it quickly expanded to include a vast array of political dissidents, human rights lawyers, members of the LGBTQ community and journalists.

Among them was Al Jazeera’s reporter Mahmoud Hussein, who was detained in 2016 upon his arrival in Cairo to visit his family. Hussein completed two years in prison without charges, trial or conviction, in December last year, which experts say is a violation of Egyptian and international law.

An NGO law issued by Egyptian authorities in 2017 effectively banned independent work by nongovernmental groups, allowed for the prosecution of dozens of Egyptian NGO workers, froze the assets of many human rights defenders in the country and issued travel bans against them, according to an HRW report published earlier this month.

That same year, Egypt imposed a state of emergency which has, according to experts, allowed the state to abuse counterterrorism and media laws to suppress basic freedoms.

Since el-Sisi secured a second term in 2018, HRW says his security forces further escalated their “campaign of intimidation, violence, and arbitrary arrests against political opponents, activists.”

Analysts believe this campaign is likely to continue following the amendments, “even if currently the civil and political space is already incredibly restricted, and there are tens of thousands of people languishing in Egyptian jails on political grounds,” explained HRW’s Page.

|

|