In deep water: Meeting Spain’s sunken treasure hunter

Marine archaeologist Carlos Leon faces threats from professional scavengers who want to steal his treasure maps.

Madrid, Spain – For centuries, pirates tried to “liberate” the gold, silver, emeralds and other valuable gems plundered from Latin America and transported across the seas in Spanish galleons.

Today, Carlos Leon is searching for the same loot – only this time he wants to preserve it for future generations instead of carrying it off for himself.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsSubmarine packed with cocaine captured in Spain

Spain exhumes Franco’s remains from opulent mausoleum

The marine archaeologist leads a team from Spain’s culture ministry on a mission to track down hundreds of sunken ships which lie at the bottom of the treacherous waters of the Americas.

The hunt begins on Christmas Day 1492, when Christopher Columbus’s flagship Santa Maria sank off the coast of what is now modern-day Haiti.

Over the following four centuries, as the Spanish maritime empire first prospered then foundered, the seas swallowed up untold treasures.

Leon, along with fellow archaeologist Beatriz Domingo and naval historian Genoveva Enríquez, has catalogued many of the wrecks of the ships that forged and maintained the empire.

They have so far logged 702 shipwrecks off Cuba, Panama, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Bermuda, the Bahamas and the US Atlantic coast.

The inventory runs from the sinking of the Santa Maria to July 1898, when the Spanish destroyer Pluton was hit by a US boat off Cuba, marking the end of the Spanish-American war and the closing chapter of Spain’s imperial age.

“The point of our work is to preserve all this, not for Spain’s national heritage but for the international heritage – so people know about this maritime history,” Leon told Al Jazeera.

“Much is known about the most famous ships, but there is a huge number of other ships of which we know virtually nothing. In many cases, we don’t know how they sank or why.”

By scouring the archives of maritime museums in Seville and Madrid, the team has discovered most of the information about long-forgotten galleons and more modest transport ships, which carried anything from religious relics, clothes for slaves or mercury from Spain to their empire in Latin America.

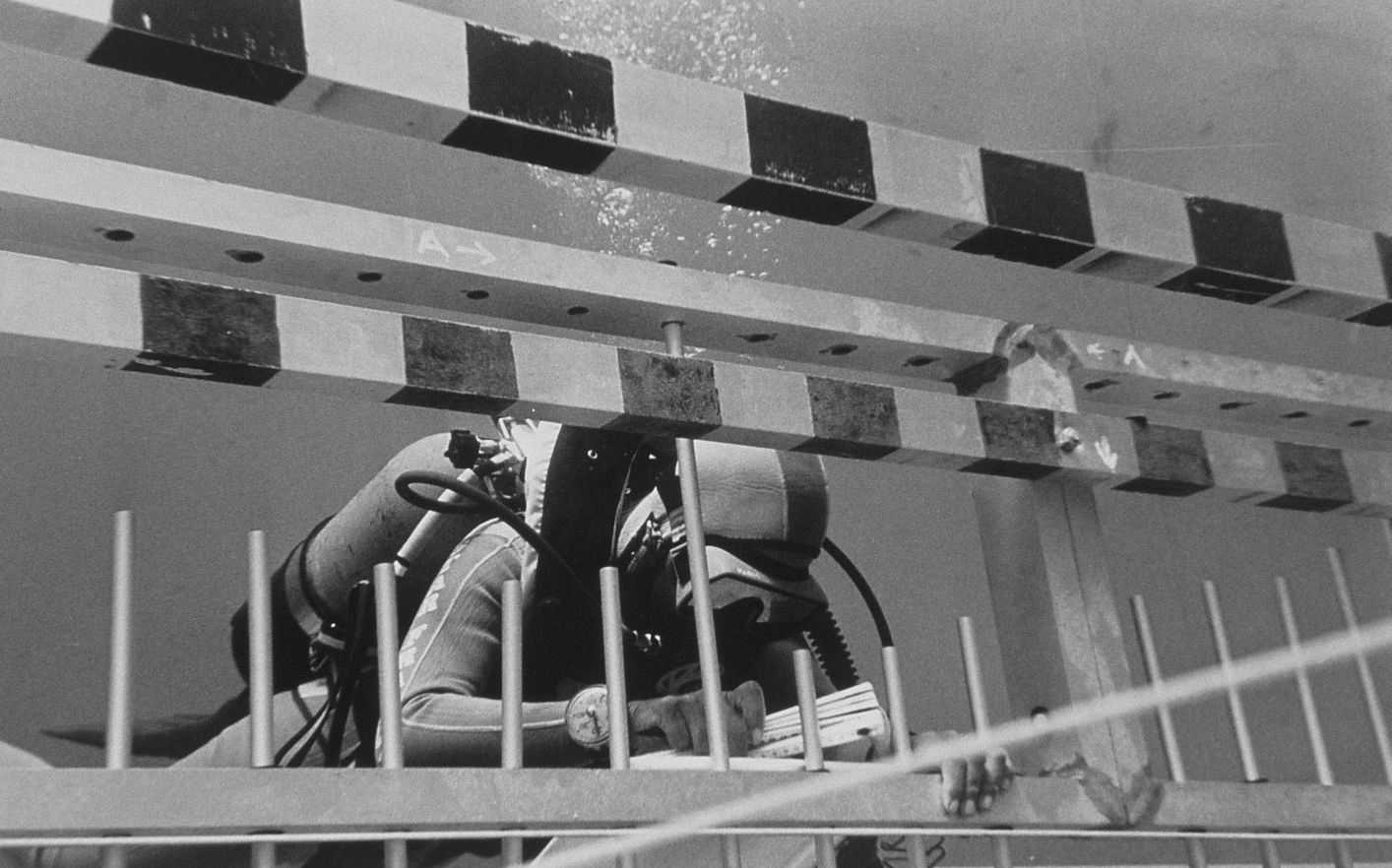

Sometimes, Leon, a trained diver, must himself descend to the depths to inspect wrecks which might just contain treasure.

In the high-stakes business of treasure-hunting, Leon may hold the key to where fortunes lie at the bottom of the sea.

This has made him a target for professional scavengers, who would like to steal his top-secret treasure maps.

“Sometimes I need the protection of armed bodyguards, police or even the army,” said Leon.

“In countries like Panama or the Dominican Republic or around the US coast, where these treasure hunters are well-established, then they want to steal information I have about these wrecks on my computer or in notebooks.

“I have never been scared,” he said. “I know I will be protected.”

Spain normally seeks only to preserve wrecks, not to recover lost treasure – unless commercial hunters try to raid shipwrecks to take away the gold, silver or other valuables.

Sensitive negotiations are still taking place over what is believed to be the largest treasure haul ever discovered, worth some $20bn.

In 2015, the Colombian government announced it had discovered the wreck of the Spanish galleon San Jose.

A remotely controlled robot found the wreck lying on the sea bed, but the exact location was kept a closely guarded secret.

After a gun battle with British ships, the galleon sank on 8 June, 1708 off the coast of Cartagena in Colombia, taking with it 600 crew and a fortune in gold, silver and jewels.

The late Nobel laureate Gabriel Garcia Marquez mentions the galleon in his book Love in the Time of Cholera.

Colombia at first said it would work with the Swiss treasure hunting company Maritime Archaeology Consultants (MAC) to recover the treasure.

However, after a change of government this year, the country’s approach to the San Jose steered a different course.

Maria Lucia Ramirez, the current Colombian vice president, has said the treasures discovered on the ship will remain part of the national heritage.

“For this government, we will not pay to recover what is on the wreck. Whatever is there may have a great economic value but more important than anything, whatever is recovered has a great cultural and historical value for Colombia and the world,” she said.

Spain has been maintaining bilateral talks with the Colombian government over the fate of the galleon and will offer scientific aid to recover the treasure.

Jose Guirao, of the Spanish culture ministry, said: “The change of position of the Colombian government is important because it sends out a message to other countries who might be tempted to cooperate with [treasure hunting] companies who will put easy economic gain above the cultural value of what is on this wreck.”

Al Jazeera contacted MAC, but the company declined to comment.

Spain’s trawl through its maritime history has revealed much about what navigation was like in the past, providing interesting insights for serious naval historians.

However, the project has also served to dispel many romantic notions about the Jolly Roger, pieces of eight and buried treasure.

The vast majority of ships sank, not because of the efforts of swashbuckling pirates, but rather bad weather.

Leon found that 91.2 percent of wrecked ships were sunk by tropical storms and hurricanes.

Another 4.3 percent ran on to reefs or other navigational problems, and 1.4 percent were lost to naval engagements with British, Dutch or US forces. Only 0.8 percent were sunk in pirate attacks.

“The worst enemy for most ship captains was bad weather or rocks near the shore. Pirates were not a big problem at all in reality. And even enemy fleets hardly figured, according to our research,” said Leon.

He and his colleagues have discovered that the seas around Panama, the Dominican Republic and the Florida Keys have the largest number of wrecks.

|

|

Instead of two or three wrecks per bay, they have discovered as many as 18.

The high maritime casualty rate along these coasts is a result of the shallow waters, with many ships foundering on the rocks.

“Ships are a little like aeroplanes,” said Leon. “They usually crash on take-off or landing. In this case, the vessels sank in shallow waters near ports, or as captains were trying to shelter from storms by bringing their crafts into ports.”

His inventory will be shared with other countries with colonial shipwrecks in their waters to help them safeguard their naval history.

Spain works with countries which have ratified the 2001 UNESCO convention on the protection of the underwater cultural heritage.

This ensures these countries do not use the information supplied by Spain to make deals with professional scavengers.

“It may help to save wrecks from the treasure hunters who care nothing about these sites but just want to strip them of the gold or silver,” he said.