Polls close in Sri Lanka’s critical presidential election

Results of the vote, held amid heightened religious tensions and stuttering economy, expected to be announced on Sunday.

Colombo, Sri Lanka – Polling has closed in Sri Lanka‘s presidential election that has seen rising religious tensions and a slowing economy take centre-stage for voters, officials say, with results expected to be released on Sunday.

Polls closed at 5:00pm local time (11:30 GMT) on Saturday after a largely peaceful election that did albeit see several incidents of limited violence, Election Commission Chairman Mahinda Deshapriya said.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsSri Lanka presidential election

In Sri Lanka, presidential election deepens religious divisions

“We are very happy to say we don’t have any very serious incidents of what we would call violence,” Deshapriya told reporters in the capital Colombo.

Previous presidential polls in the South Asian island nation have been marred by rioting and clashes between rival political groups.

Counting of votes was under way by commission officials, and a final result was expected by Sunday evening, he said.

Earlier on Saturday, unidentified gunmen fired on a convoy of more than 100 buses carrying mainly Muslim voters near the northern town of Thanthirimale, about 190km north of Colombo, police said.

Three buses were damaged, but there were no injuries, police spokesperson Nuwan Gunasekara said.

“Thanthirimale police is conducting the investigation, but so far no suspects were arrested,” Gunasekara said. The voters safely reached their destination and voted, he said.

On Saturday evening, another bus carrying some Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) was pelted with stones when it was returning to Puttalam town in northwest Sri Lanka, police said. Two women, aged 54 and 55, were injured in the attack, they added.

Saturday’s election saw Sajith Premadasa, a cabinet minister and ruling United National Party (UNP) candidate, take on Gotabaya Rajapaksa, a former secretary of defence and brother of two-time former President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

Rajapaksa’s Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) ran a campaign focusing heavily on national security following a series of coordinated suicide bombings that rocked the country in April, killing 269 people.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa has said he would appoint his brother Mahinda as prime minister if he is elected.

Premadasa, whose father was assassinated when he was president in 1993, focused on the country’s slowing economy, promising to boost pro-poor welfare programmes, particularly in the housing sector.

‘We need a strong leader’

Gunasekara said at least 26 people had been arrested across the country on the polling day for violating electoral laws.

According to the Election Commission, at least seven incidents of violence took place on Saturday, including allegations of shootings, stabbings and assault. At least 248 other electoral law violations were also reported, Election Commission chief Deshapriya told reporters.

According to the independent Centre for Monitoring Election Violence (CMEV), at least 196 violations were reported on the election day, including at least three assaults and 61 cases of intimidation.

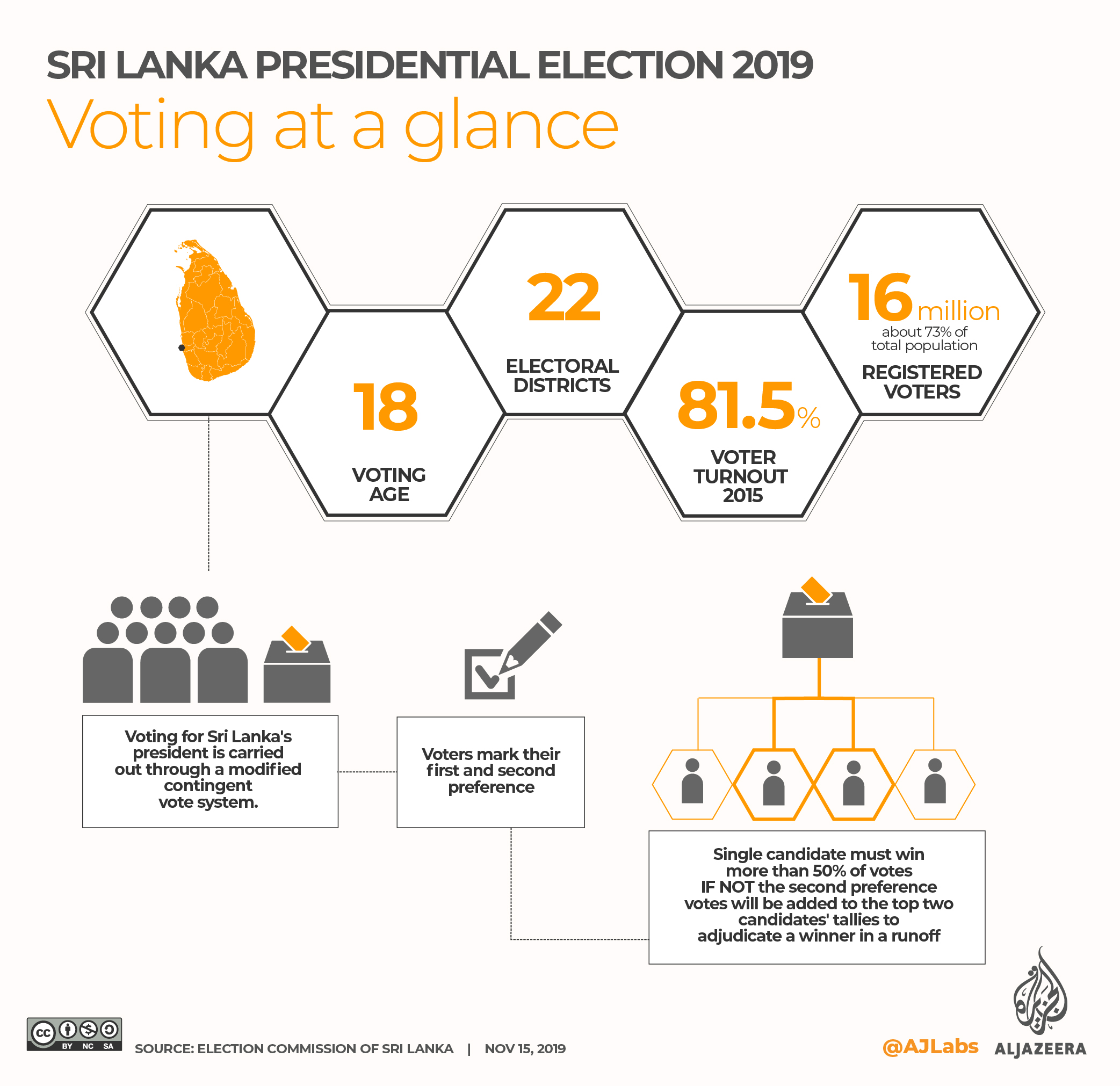

Voter turnout was expected to be high, with Deshapriya predicting a final figure of more than 80 percent. During the last presidential election, in 2015, voter turnout was a similar 81.5 percent.

In Colombo, many voters said they were voting due to concerns about the country’s economic situation.

Burdened by high foreign debt – much of it accrued during post-war reconstruction under Mahinda Rajapaksa – and slowing economic growth of 2.7 percent, the island nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) has begun to stagnate.

“We are poor people, and whoever comes as president should help the people,” said Sandya Kumari, 59, a cleaner who voted for Premadasa.

Others said Rajapaksa’s message of strong, centralised leadership resonated with them.

“He has done good work and proved himself, and we need a strong leader, more than anything else,” said Jayantha Abeywickrama, 50, a lawyer.

Rajapaksa’s campaign focused on his tenure as defence secretary during his brother’s terms as president, particularly his leadership at the end of the country’s bloody 26-year civil war against Tamil rebels in 2009.

Rights groups have long called for accountability into alleged rights violations carried out in the final days of the war.

According to a United Nations report, as many as 40,000 Tamils might have been killed by indiscriminate bombing into areas previously deemed “no-fire zones” by the Sri Lankan military, as the rebels retreated into civilian areas.

Tamils form roughly 15 percent of Sri Lanka’s 21.8 million population, living mainly in the northern areas of the country.

“We have a right to vote, but we are not getting anything from it,” said Poulasingham Sridarasingh, 67, a Tamil bookstore owner in Colombo.

The country’s roughly 10 percent Muslim population has also come under a series of attacks during riots and protests since the Easter Sunday bombings, which were claimed by the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS).

Rajapaksa launched his campaign days after that attack, promising to make national security a key concern. He has been backed by a number of hardline Buddhist nationalist leaders who have called for greater controls to be placed on Muslims.

Imran Muhammad Ali, 38, a voter in Colombo’s Nugegoda area, said he would “never” vote for the Rajapaksas.

“They did a good thing by ending the war, but maybe not by the means that I would have wanted,” he said. “If they do win, they will stay in power for 30 or 40 years.”

The later years of Mahinda Rajapaksa’s presidency were marked by an increasing crackdown on dissent, including disappearances of activists and journalists.

“The future of Sri Lanka, how our rights and security is protected will be decided by who will be selected by the people today,” said Sandya Eknaligoda, a human rights activist and wife of journalist Prageeth Eknaligoda, who went missing in 2010, two days before Mahinda Rajapaksa won re-election.

His disappearance was linked to a military intelligence unit, the Sunday Observer newspaper reported.