Ratko Mladic’s ideology lives on in Republika Srpska

Mladic’s vision of an ‘ethnically cleansed’ Greater Serbia is a reality today with Bosnia’s Republika Srpska entity.

Sarajevo, Bosnia, and Herzegovina – In the early morning of July 10, 1992, the Bosnian Serb Chetnik army forced residents out of their homes in the village of Biljani, in western Bosnia, separating the men and women.

They set their houses on fire, killed the men and thew their bodies in a deep cave. Then they told the survivors they could go back to their homes.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsAs Israel attacked Gaza’s north, 26 members of his family were wiped out

What is Trident, the US floating pier off Gaza? Will it work?

Does Israel’s Netanyahu have a plan for a ‘day after’ the war on Gaza?

When the women and children returned, they witnessed a devastating scene: everything had been burned to the ground, with their husbands and fathers nowhere in sight.

Amina Sljivo Becic was only four days old at the time when she lost her grandfather and 10 other family members in Biljani.

“Yesterday, when they sentenced 74-year-old Mladic to life in prison, I asked myself, ‘So, what now?'” recounted Becic, 25.

“Nothing can bring back my grandfather, who was overjoyed at the arrival of his first grandchild, me, who he didn’t even get the chance to meet. Nothing can bring back the fathers of my friends,” she said.

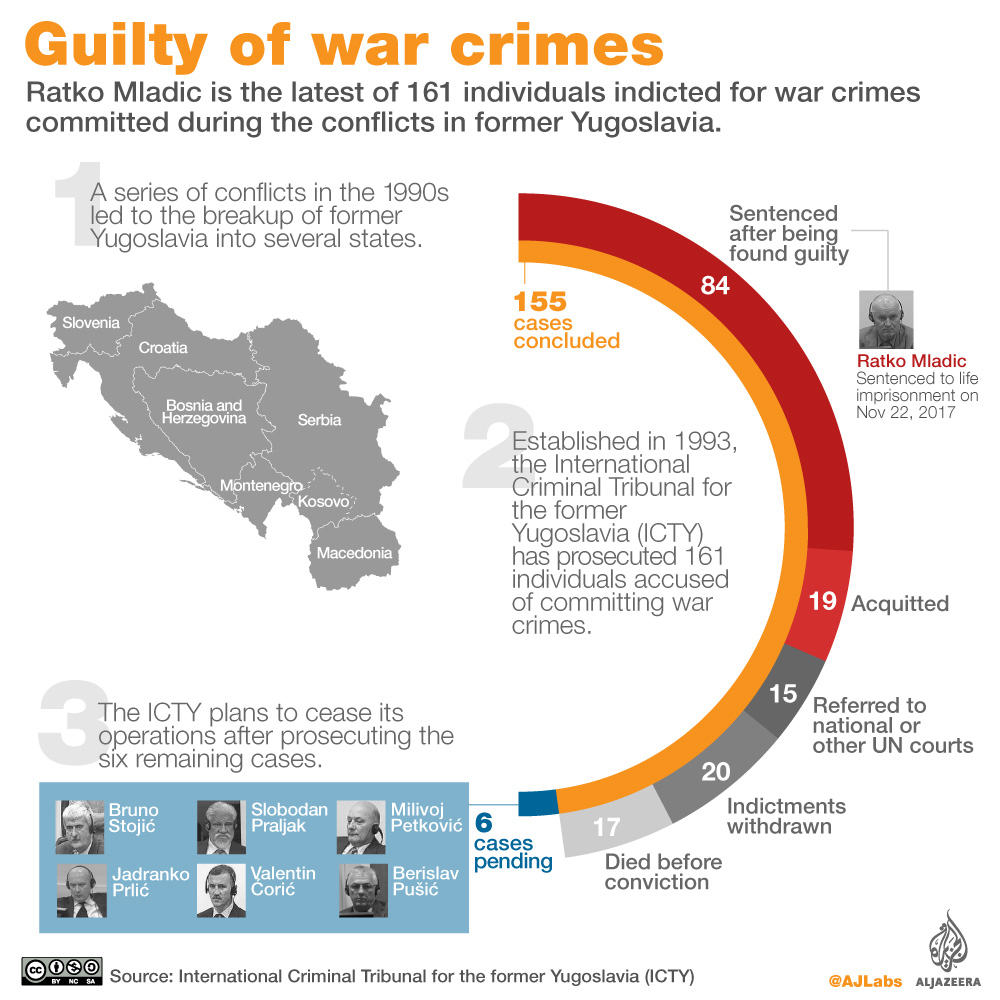

On Wednesday, the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague sentenced former Bosnian Serb military chief Ratko Mladic to life in prison.

The court found him guilty of 10 out of 11 counts, charged with genocide and war crimes committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the early 1990s.

While the court found the general “significantly contributed” to genocide in Srebrenica in July 1995, it was “not convinced” of genocidal intent in six other municipalities.

“I don’t think the verdict against Ratko Mladic has satisfied justice, especially since the international community wants to throw dust in our eyes, wants us to be satisfied with the conviction for genocide in Srebrenica,” Becic said from Sarajevo, capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

“But the six other municipalities weren’t treated in the same way. Percentage-wise, Biljani had the most victims.”

More than 260 civilians were killed that day in Biljani, 15km west of Kljuc, one of the municipalities where Mladic was accused of committing genocide. Only about 50 men from the village survived – those who were by chance out in the orchard that day or working temporarily abroad.

After spending 16 years in hiding and five years standing trial, Mladic was also found guilty of carrying out and overseeing a deadly campaign of sniping and shelling of Sarajevo.

War victims agree that the charge of genocide should have applied to the six additional municipalities across Bosnia as well.

However, they are still “partially satisfied” with the outcome, since Mladic was found guilty of “heavy qualifications”, calling it a “historical verdict”.

While the ICTY prepares to shut down next month, victims still find little closure as reminders of the brutal war and threats of a subsequent one are ubiquitous.

Twenty years on, the country’s political scene is still of serious concern.

“I think Mladic’s arrest and trial went on for a very long time,” said Munira Subasic, who managed to bury two bones of her son just a few years ago.

“While this was going on, a lot of Mladics were born in Bosnia and Serbia. I’m not worried about Mladic himself anymore; he will end up where he belongs. But I’m worried about these other, newly born Mladics who are perhaps even worse than Mladic himself.”

Mladic’s vision realised

More than 100,000 people were killed during the war in Bosnia, while as many as 50,000 women were raped.

On November 21, 1995, the Dayton Peace Accords officially ended the three-and-a-half-year war, dividing Bosnia and Herzegovina into two semi-autonomous entities: the Bosniak-Croat “Federation” and the Bosnian Serb “Republika Srpska”.

Today, Mladic’s vision of an “ethnically cleansed” Greater Serbia is a reality in the form of the Republika Srpska entity. Support for Mladic is widespread among Serbs in the Serbian entity and Serbia alike.

On the day of his verdict, posters of Mladic were put up on the streets of Srebrenica, in Republika Srpska, reading: “You are our hero!”

Following Mladic’s verdict, Milorad Dodik, the president of Republika Srpska, stated in a press conference that “a spot as a hero was reserved for Mladic long ago and this verdict can’t change that”.

“[Mladic was] a man who prevented a new genocide on Serbs in both Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia … This is just one more shameful slap for Serbian victims,” said Dodik.

For years, Dodik has repeatedly called for Republika Srpska’s secession and openly denies that genocide occurred in Srebrenica.

Srebrenica’s first Serb mayor, Mladen Grujicic, who was elected last year, shares this belief.

“With their rhetoric, they’re supporting younger generations in glorifying him as a hero,” said Fikret Grabovica, whose 11-year-old daughter was killed by a shell in besieged Sarajevo in 1993.

“It’s tragic to praise this criminal as a hero; this will affect the youth, many of whom still don’t know the real truth. They don’t want to be told the real truth; they are actually misinformed.”

In recent years, reports of the Serbian Chetnik paramilitary group gathering and marching across the Serbian entity have been published in the news media.

They openly threaten another war in Bosnia and spread messages of reclaiming territory. Yet, this has not spurred any reaction from authorities.

![A mural of Mladic is seen on a building in Gacko, Bosnia and Herzegovina [Dado Ruvic/Reuters]](/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/100ec14af7964678a89879b6839d4441_18.jpeg)

Buildings and streets have been named after convicted war criminals and memorials have been set up in their honour. One such memorial praising Mladic was set up in Bosnia’s capital Sarajevo in 2014 on the line dividing the two entities.

Srdjan Susnica, an attorney from Banja Luka, Republika Srpska, explained to Al Jazeera that the Bosnian Serb society is not “coming to terms with what happened, with the facts”.

“The Hague tribunal in this part of Bosnia is completely demonised, discredited,” said Susnica.

“[We have here] a relativisation of crimes, glorification of war and war participants. In Banja Luka, in the last five, six years, we’ve had streets renamed after people who were bandits, robbers during the war.

“Ratko Mladic’s political idea was rewarded with the [Republika Srpska] entity,” said Susnica. “Republika Srpska’s youth have been raised on narratives of Great Serbia’s legacy.”

Meanwhile, in Serbia the media has left residents largely uninformed about the atrocities that occurred next door. According to an IPSOS poll conducted in October 2011, nearly half of residents in Serbia did not know why Mladic was standing trial at The Hague.

Only 15 percent of residents believed that more than 7,000 people were killed in Srebrenica.

“Residents say for instance, ‘I’ve never even heard of that event’. For example, Sarajevo was under siege for over 1,000 days, yet only 53 percent of residents said that they’ve heard about this,” said Svetlana Logar, of IPSOS.

Researchers say the media in Serbia simply has not been reporting on the crimes committed by Serb forces in neighbouring Bosnia. Following the news of Mladic;s landmark verdict, some of the headlines featured in Serbian newspapers the next day included: “All of Ratko Mladic’s secrets”, “The Hague’s doctor Mengel is killing Ratko Mladic”, referring to the military chief’s heath issues, and “Is The Hague tribunal the biggest concentration camp for Serbs?”

Like Susnica, Marko Attila Hoare, historian at London’s Kingston University, believes the creation of Republika Srpska by way of the Dayton peace agreement drafted in November 1995 has been fostering anti-Bosnian nationalism and curbing Bosnia’s progress.

“Bill Clinton and Richard Holbrooke [creators of the Dayton agreement] saved Ratko Mladic’s genocidal project Republika Srpska from destruction and legalised it,” said Hoare.

“Bosnia was destroyed as a functioning state and multi-ethnic society, and an ethnically homogenous Republika Srpska was established on its ruins.

“As long as the Dayton system persists, you can’t really have stabilisation. The issue of Republika Srpska’s threats of sovereignty and of Bosnia’s territorial unity would have to be resolved by conflict eventually … Bosnia and Herzegovina cannot go on the way it’s been going indefinitely.”

Follow Mersiha Gadzo on Twitter @MersihaGadzo