Out of sight: Imprisoned in Iran

American-Iranians jailed in Iran suffer the brunt of the broken diplomatic relations between the two countries.

When it comes to its place as one of the world’s more prolific jailers, Iran does not rank first.

That distinction falls to the US.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe Lost Souls of Syria – Part 1

Is the US shipping weapons to Israel tacit support for its war on Gaza?

Nakba remembered: What is the right of return?

According to the International Centre for Prison Studies, Iran ranks 42nd out of a list of 221 countries. And yet, it is among the most mysterious of jailers.

Detainees are typically not allowed to contact an attorney until after they’ve been interrogated and charged with a crime – the nature of those crimes – including being “an enemy of God” can be tough to disprove in court.

Detentions as “projects”

The thing about Iran is that it also subjects citizens of other countries to its laws, as it does not recognise Iranians with multiple or dual citizenships.

The fact is that if the relationship wasn’t as bad as it is, then even the absence of diplomatic relations could have been addressed in some creative way. But because the relationship is so bad, and that the priority of the United States is on the nuclear issue, we’re not seeing resources being put on these human rights cases

If one is born to an Iranian father, one is an Iranian – even if born and raised outside the country. In order to visit Iran, anyone within this category must apply for an Iranian passport. It’s laws are blind to other passports held by Iranian citizens.

It is therefore impossible to say just how many multi-or bi-national Iranians there are imprisoned in Iran.

“The Iranian government does not provide any transparent statistics about any aspect its prisoners of conscience, especially multi-nationals or bi-nationals,” said Hadi Ghaemi the executive director of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.

“Indeed, the Iranian government rejects the notion of anyone having a dual nationality.”

This is what made journalist Roxana Saberi, a US citizen born in the US to an Iranian father, vulnerable to Iranian laws when she was arrested and charged with spying in 2009.

Saberi, who did not respond to a request for an interview, had lived and studied in Iran without incident since 2003, but six months before the contentious 2009 presidential elections, she was arrested in January and received an eight-year sentence.

All told, Saberi got lucky and possibly benefited from one of the very fleeting, golden, diplomatic moments between Iran and the US.

President Barack Obama had started his first term in office and reached out to the Iranian government – a massive turnaround the relations coming off the tail of the George W. Bush years, when Iran had been designated a member of the so-called “Axis of Evil” countries.

By May 2009, after Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad intervened on her behalf (a rare and remarkable gesture) urging an appeals court to reject Saberi’s sentence, she was freed.

“Those who are trying to engage the US won out,” the New York Times quoted an unnamed US senior official saying at the time of Saberi’s release.

“There wasn’t going to be any major new administration initiative toward Iran without this case resolved.”

It’s worth noting that in a September 2010 interview with Al Jazeera, Saberi herself focused on “international outcry” as the reason the Iranian government ultimately released her.

Ghaemi is not sure if Iran meant to use Saberi’s release as a gesture of goodwill toward the Obama administration, but feels that international press and media attention certainly helped her case.

“That is exactly why interrogators do not want that, because they feel like that will derail their project,” said Ghaemi.

“These detentions are very much projects that are determined from before, and [the detainee] is someone they’re looking for to fill the role as the alleged spy or agent.”

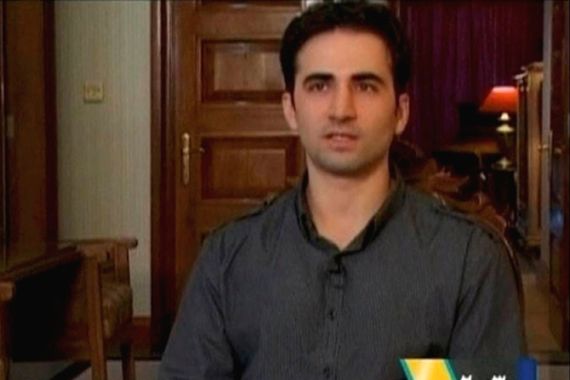

Amir Hekmati has not been so fortunate.

‘Political prisoner’

Born in Arizona, Hekmati joined the Marine Corps right out of high school and ended up serving in Iraq as a translator from 2001 to 2005. Since leaving the service, he worked as a translator in the US, and his trip to Iran in the summer of 2011 to visit his grandmother was his first visit to the country.

Prior to making the decision to leave, Hekmati disclosed his military history to the Iranian authorities and was assured that it wouldn’t be an issue.

He was picked up roughly two weeks after his arrival. Since then, he’s been charged, tried and convicted on spying charges, using material he was carrying with him (his identification, camera, etc.).

Iranian State media also aired a 17-minute taped “confession,” in which footage of his statements is heavily cut with a narrated series of clips meant to connect his statements with spying programmes Iran says are run by the CIA and Israel’s Mossad.

This is common practise in Iran, where prisoners are either asked to confess in exchange for a more lenient sentence or are coerced into doing so as a means of protecting their families or associates.

Hekmati, 29, has been put on and then taken off death row.

“Their tactic is always to tell you that nobody on the outside world cares about you. If you repeat what we tell you, if you talk the way [we want] we’re going to help you,” said Haleh Esfadiari, director of the Woodrow Wilson Middle East Program, who herself was jailed in May of 2006 and released three-and-a-half months later.

“There is a sense of depression, that you’re completely cut off from the outside world…I can sense the despair of the political prisoner or any prisoner who is cut off,” said Esfandiari.

Hekmati’s family in the US has been turning itself inside out trying to secure his release. They’ve been told that he spent 16 months in solitary confinement until his alarming mental and physical breakdown – due in part to a hunger strike – prompted authorities to move him, allowing him to mix with other inmates.

The family noted during the rare and brief visits with Amir that his once fit, athletic physique was diminished and his demeanour withdrawn.

His sister, Sarah Hekmati, said the family has been in anguish since the start of the ordeal, which seems to follow no procedure and have no end.

Their father, Ali, has been diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour and is, she told Al Jazeera, undergoing radiation and chemotherapy, “working hard to stay strong with hopes that he will survive and see his son again.”

Describing her family as apolitical, Hekmati, a school counsellor in Detroit, Michigan, said she does not wish to consider whether her brother is being used as a political tool between the US and Iran.

“But we have been told this many times by political analysts and experts in US-Iran relations so it is not unheard of that there is a political scope to Amir’s case. He is, after all, being detained in the political prisoner ward of Evin prison.”

No progress

The family posts optimistic messages on the FreeAmir site, where they’d expressed their hopes that the Iranian authorities would see fit to free Amir by March 20, the Persian new year as marked by the vernal equinox.

But it’s been over 600 days.

””We

freed.””]

When the Hekmatis first heard of Amir’s arrest, his sister said the family hoped that his freedom would be secured via diplomatic channels.

“We knew the US and Iran had a more than strained relationship and that working through diplomatic channels within Iran would be more effective. We initially reached out to the Iranian Interests Section in Washington DC and the UN Iranian mission for help,” said Sarah Hekmati.

Initially, on the advice of Iranian authorities, the family refrained from reaching out to US officials, fearing that doing so would create more friction in an already tense situation.

“The case of Amir Hekamti is an unfortunate one because it is essential that during the first month of detention, as much attention be paid to the case as possible,” said Ghaemi.

“Now it is true that the US government isn’t doing much in the case of Amir Hekmati, and the best option for the Hekmatis is really to raise his profile internationally – to talk about him as a human being and to demand accountability and release. They must make it clear that he is a son, a brother, a human being being treated like this,” said Ghaemi.

“It takes a lot of effort to get the attention of the international media, given that much of their attention is also focused on the nuclear issue.”

Sarah Hekmati said that once the US authorities were alerted to her brother’s imprisonment, US officials contacted the family through weekly conference calls, keeping the them updated with developments.

But due to the lack of any real channel for direct dialogue, the US, she said, would submit requests to Iran’s foreign ministry via the Swiss.

“All of these efforts were denied by the Iranian authorities,” said Hekmati, adding that other requests were made via international channels, such as Turkey, which also went nowhere.

Coming to a dead end with the diplomatic means available to them via the US, the family is now making an appeal through the United Nations, where Amir’s case is currently being investigated.

A source at the US State Department who cannot be named told Al Jazeera that the Privacy Act prevents the State Department from commenting on specific cases.

“But broadly speaking, we obviously take the plight of American citizens that are incarcerated overseas very seriously, and we certainly do make every effort possible on their behalf,” said the source.

The source could not confirm if other governments have been engaged as intermediaries to help free Hekmati or if his case – or the case of Saeed Abedini, whose crime is converting to Christianity – in addtion to their detentions have been the topic of diplomatic talks at any level.

“Iran in particular is very unique because we don’t have direct diplomatic relations with them, so we’re using every opportunity we can to raise their cases and to encourage others to do so, but it’s difficult to say why it works in some individual cases and not in others. It depends on how the [Iranian] legal system is viewing each case,” she said.

The source said the State Department is not aware of exactly how many American-Iranian citizens are currently incarcerated in Iran, but said that “it’s not a large number…and from the Iranian perspective, it’s zero.”

International pressure: Filling the diplomatic void

The case of Iranian-American academic Kian Tajbakhsh was in the headlines at roughly the same time as Esfadiari’s. Arrested in May of 2007, Tajbaksh was released five months later, only to be arrested again in July 2009 – shortly after the presidential elections – and charged with espionage.

Like Hekmati, hopes for Tajbakhsh’s release were pinned on international pressure.

“We did not make a significant effort with the United States government,” said Aryeh Neier, president emeritus of the Open Society Institute, for which Tajbakhsh was conducting research in Iran on both drug treatment programmes as well as the potential for intellectual exchange.

“We were certainly in touch with US government officials, but we didn’t see them as the main actors who could exercise some influence. The relations between the United States and Iran are such that the US was not going to play a very helpful role in getting him freed,” said Neier.

He added that they looked to other governments that had better relationships with Iran to help facilitate dialogue.

But there wasn’t any progress until Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was allowed to speak at Columbia University (where Tajbakhsh had earned a PhD) in September 2007.

That same month, Tajbakhsh was released for the first time, something circumstance connects with Ahmadinejad being given a platform – however controversial – at the university. Still, Neier admits that this is only guess on his part.

“Obviously, the Iranians didn’t tell me why Kian was freed.”

The reasons for one’s release can be as arbitrary and mysterious as the reasons for one’s arrest, but political discord seems to play into both capture and release more often than not.

And isolating a system like Iran’s via cut ties and acrimony only makes matters worse, in Neier’s view.

“Our general view is that if you’re dealing with a repressive country, you don’t want complete intellectual isolation. You want to have people to be able to have contact, and that is our reason for being in Iran,” said Neier.

“I’m personally a believer in the use of economic sanctions as a way of promote human rights, for example, but I would exempt from economic sanctions anything that involves basic human needs – medical supplies, food, those things that serve a humanitarian purpose.”

Neier does not support isolating a country such as Iran, even though it might seem like having any engagement with the state – intellectual or diplomatic – might be used to strengthen the regime’s legitimacy.

“You can find ways to counter that….If you’re dealing with basic human needs, that is not something that ought to be subject to economic sanctions, and intellectual exchange should not be subject to sanctions.”

For the Hekmatis, the sanctions and isolation have only increased the distance they have to travel, diplomatically, to get their son and brother home.

“The only promising things we have heard are that our attorney continues to push for appealing for Amir’s release and has encouraged us to write letters to the Supreme Leader which we have done,” said Sarah Hekmati.

The family remains grateful that Amir’s death sentence – which was in place for three months, was annulled due to lack of evidence.

But until he’s home the Hekmati family will not breathe an easy breath.

No leverage for human rights

Trita Parsi, president of the National Iranian American Council, said that as things stand, there’s simply no way for the US to even discuss human rights cases with Iran.

“The bottom line is, in the absence of a relationship – meaning a diplomatic presence, etc. – there’s very little the US can do,” said Parsi, whose book, “Single Role of the Dice” outlines the Obama administration’s diplomatic policy with Iran.

“The fact is that if the relationship wasn’t as bad as it is, then even the absence of diplomatic relations could have been addressed in some creative way. But because the relationship is so bad, and that the priority of the United States is on the nuclear issue, we’re not seeing resources being put on these human rights cases,” said Parsi.

|

| Esfandiari, while detained in Iran, appeared on state TV but did not confess to the espionage charges against her [EPA] |

He pointed out that presently, the only bilateral talks sought by the US with Iran (rejected by the latter) focus on nuclear issue alone

“I find this very problematic. It’s an unfortunate decision,” said Parsi, because, he said, the truth of the matter is, no one “wins” in a diplomatic vacuum.

While things were far from perfect under Iran’s last reformist president, Mohammad Khatami, Iranian human rights activist Ghaemi said that there was “more communication between governments” during Khatami’s administration.

“That meant that there was a consistent channel to Tehran between various players and stakeholders to send their message to Iran about a particular detention,” said Ghaemi.

“Since [Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad took office, very few countries, such as Turkey, Qatar and Brazil, have been particularly willing and active in trying to secure the release of bi or multi-nationals,” said Ghaemi.

This is a source of frustration to those who hope for better diplomatic relations with Iran.

“We have very little leverage or ability to affect the human rights situation, not just for the US citizens stuck in Iran, but for the general human rights situation over there for which the US criticises the Iranian government,” said Parsi.

As it stands, bi- or multinationals, he says, suffer “in a double way” by virtue of being imprisoned and having no access to consular services.

“Amir’s case stands out because here is a young man who served the US, and yet, the government seems impotent in freeing him,” said Parsi.

Still, he feels there is a way forward.

If anything, he says that the nuclear issue – a compelling one – shows that even when Iran and US know they need to talk, it’s not easy for them to do so.

“One of the potential positives that could come out of the nuclear issue is that if there is a more established channel of communication between the two countries, then that will also provide opportunities to talk about these [human rights] issues, which currently aren’t on the agenda, unfortunately.”

Two citizenships, zero rights

That Iran doesn’t even consider other nationalities of Iranians, as bi- or multinationals – is as telling as the uptick in the high-profile arrests of said citizens there.

Parsi told Al Jazeera that part of the motivation for the high-profile arrests, especially starting in 2008-2009, was to reinforce the notion that the Green Movement wasn’t a domestic opposition movement but manufactured by foreign forces.

The cases, he said, are created with the intent to “gain leverage over the US by trying to create an impression that the government narrative has a lot of validity to it – the idea that the West is really out to get Iran and that it is besieged by hostile forces.”

Esfandiari said that being a professional – not necessarily a high-profile one – can put one at risk.

“The Iranian government is very suspicious of dual citizens who are professionals and with activities connected to Iran. Otherwise there are several hundreds of thousands of dual citizens who go back every year, and come back without a problem,” said Esfandiari.

As arbitrary as it seems at times, there is a certain logic to Iran’s pattern of detentions.

“I can say that the Iranian intelligence and security services targeting of the multinationals in what they believe to be opportune moments, detaining then in a way to impact foreign and domestic policy, is a fairly regular practice of the Iranian government,” said rights activist Ghaemi, adding that he can’t think of any other state that “so routinely” has allowed its intelligence and security services to behave that way.

Still, Esfandiari, a prominent academic, who wrote about her ordeal in “My Prison, My Home: One Woman’s Story of Captivity in Iran,” said the lack of dialogue between the US and Iran only complicated cases such as hers.

“I believe that if Iran and the United States were talking with each other at least, and didn’t have to go through the Swiss, cases like mine wouldn’t happen, or would be resolved immediately,” said Esfandiari.

“In the case of dual citizens, Iran does not feel it’s under any obligation to officially accept foreign intervention, even from the Swiss, and the Swiss will not intervene unless officially asked by the US State Department to do so – so do you see the problem here?”

What ultimately helps, she said, is a lot of international pressure. The US, she said, is limited to behind-the-scenes activities, which don’t always yield results.

“The priority for the US has always been find a solution for the nuclear issue,” said Esfandiari.

“At least at the end of the discussion, mention your concern about human rights violations in Iran. Don’t keep silent about it.”

Follow @dparvaz on Twitter

This article is the first of a series on the subject written with the generous support of the Rockefeller Foundation, and researched during a Practitioner Residency.