The US occupation of Iraq as a noir thriller

The TV series Baghdad Central gives an interesting televised perspective on the lives of Iraqis after 2003.

Seventeen years after the American invasion of Iraq, Baghdad continues to make headlines. Just this past month massive popular protests against a corrupt regime and ongoing Iranian intervention were undermined by the extrajudicial killing of Iranian General Qassem Soleimani. Ironically, the ruthless leader of the infamous Quds Force had, at least until recently, collaborated with the United States in its struggle against the ISIL (ISIS), and therefore did not see the drone attack coming.

As reports of the assassination proliferated, images of the dilapidated city where it took place appeared on screens across the West, revealing that Baghdad has yet to recover from the 2003 war and the protracted occupation that followed. But now, for what is likely the first time, Western audiences can also get a sense of what it meant – from an Iraqi perspective – to live in Baghdad under US occupation, and, in this way, gain insight into why after so many years the country is still in a shambles.

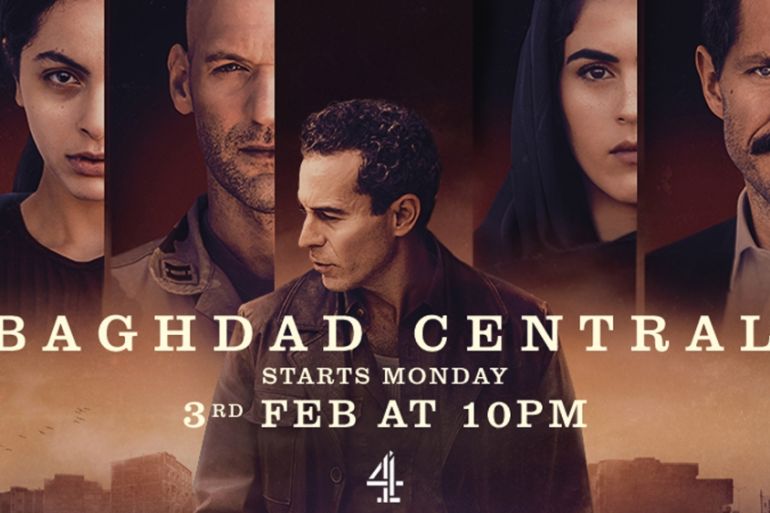

On February 3, the UK’s Channel 4 will be airing a six-part detective series called Baghdad Central. Following inspector Muhsin Khadr al-Khafaji (played majestically by Waleed Zuaiter), an ex-Baathist police officer with a dodgy background and a love for poetry, the series dramatises what it has meant to live under a foreign military power that had promised the inhabitants democracy and freedom, but failed to deliver.

Baghdad as noir

Typical of many noir thrillers, Baghdad Central’s plot is messy and the protagonists are motley. There is a talkative taxi driver, called Karl, an arrogant American military captain and an ex-police officer from the UK.

There is Zubeida Rashid (Clara Khoury), an enigmatic university professor who may be recruiting Iraqi women as translators for the Coalition Provisional Authority, or providing prostitutes to American mercenaries, or, alternatively, may actually be a leader of the newly established Iraqi resistance. There is also a mukhabarat thug, a bodyguard, a handful of opposition fighters, and al-Khafaji’s two daughters, bedridden Mrouj (July Namir) and the allusive Sawsan (Leem Lubany).

In the wake of his country’s occupation, ex-police officer al-Khafaji, like so many of those who had been employed by the Baathist regime, struggles to keep himself and his sick daughter, Mrouj, safe. When he learns that his estranged elder daughter Sawsan is missing, he sets out on a desperate search to find her, only to discover that she has been leading a double life.

Al-Khafaji is then mistakenly arrested by the Americans, interrogated and tortured Abu Ghraib style, and later recruited by Frank Temple (Bertie Carvel), who has arrived from the UK on a mission to rebuild the Iraqi police force from the ground up. “We need experienced local police officers like you,” Temple tells al-Khafaji, offering him dollars and medical treatment for his sick daughter. Left with few options, al-Khafaji, whose wife had died of cancer due to the collapse of the Iraqi health system following years of American sanctions, decides to become a collaborator.

Collaboration

By watching the twisting and twisted trail of money, sex and violence, one begins to understand that neither the collaborator nor the culture of collaboration is something that can be readily controlled. While every occupier needs individual collaborators to govern the population, collaboration gains a life of its own.

Deception necessarily infects everyone. Some use it for good, others for bad, but duplicity, corruption, and deceit, as the series suggests, are the foundations upon which the new Iraq was built.

The more al-Khafaji works for the occupiers, the more he also understands that he can advance his own ends. In fact, his story is that of an individual struggling to protect his family and those he loves as his reality and the country around him collapses.

Some of the scenes are as funny as they are tragic. For instance, upon returning to his flat after being tortured, al-Khafaji is asked about his moustache (which had been brutally torn off by his interrogators after he had been water-boarded). “It was,” he responds, “confiscated. It will be sent to Washington as an example of Iraqi culture.”

Cherchez la femme, Baghdad style

Much of the plot is taken directly from the novel Baghdad Central, written by American scholar Elliott Colla. But scriptwriter Stephen Butchard has also introduced several significant changes as he adapted the book to the screen. He introduced Frank Temple, the British handler, which may have been partially to cater to British audiences, but ends up forcibly underscoring the UK’s never-ending complicity with American imperial adventurism.

Perhaps most noticeable, however, is the pronounced role of Iraqi women characters in the script. Challenging the media representation of Middle Eastern women as oppressed victims of barbaric patriarchy and religious fundamentalism, the series presents three powerful protagonists (the two sisters and Professor Rashid) who grew up during Saddam Hussein’s reign and whose lives have become much more precarious due to the increased violence, political instability, lack of security and religious resurgence following the military occupation.

There is nothing radical or radically new about this. Feminists and postcolonial critics have, for years, demonstrated that women tend to suffer most during the war. Even though the US might present itself as fighting for women’s rights, it frequently ends up endangering and undermining further the very women it set out to “save”.

Yet, Butchard does provide a vital corrective to popular representations of Middle Eastern women, which are often informed by stereotypes and thinly veiled racism. Unfortunately, though, he may have taken this one step too far, since by portraying only powerful Iraqi women, we are offered a somewhat skewed image of the gender dynamics in the country. By contrast, the men depicted are more diverse and multifaceted.

Baghdad Central ultimately provides an intimate look at the inner workings of military occupation and the dire effects that all such occupations inevitably produce. The series importantly highlights that when corruption and violence are rife, there is no firewall to prevent them from spreading. Like a contagious virus corruption and violence end up seeping deep into the political body. Yet, unlike other kinds of exposes of these dynamics, Baghdad Central does so in an extremely captivating, and one might even say, entertaining way.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.