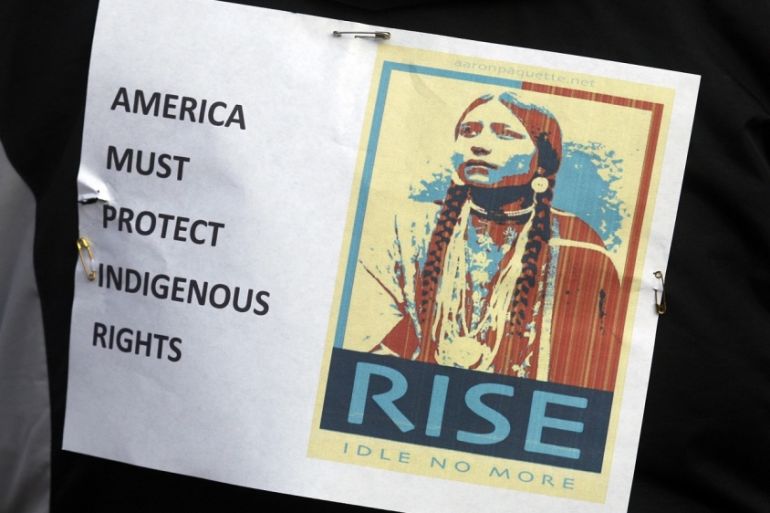

Under fire: the perpetual US war on Native Americans

On the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, Native Americans have little to cheer about.

August 9 marks International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples.

On its website, the United Nations notes that the focuses this year will include “the challenges and ways forward to revitalise indigenous peoples’ identities and encourage the protection of their rights in or outside their traditional territories”.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsPhotos: Indigenous people in Brazil march to demand land recognition

Holding Up the Sky: Saving the Indigenous Yanomami tribe in Brazil’s Amazon

Indigenous people in Philippines’s north ‘ready to fight’ as tensions rise

To be sure, the protection of indigenous rights is particularly challenging in this day and age. In various contexts around the world, the presence of indigenous communities is seen as an obstacle to profit-driven corporate exploitation and environmental despoliation.

In the United States – vanguard of the capitalist system and usurper extraordinaire of Native American land – the goal of “revitalis[ing]” indigenous identity will presumably prove formidable indeed seeing as the entire US enterprise is, in fact, predicated on the suppression of Native agency, culture, territorial bonds, and general dignity.

Also suppressed, of course, is the whole business of genocide upon which the US is built, which naturally complicates the country’s self-advertisement as the epitome of liberty, justice, freedom, democracy, etc.

Little to cheer about

In her 2015 book, An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, scholar Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz observes that “Euro-American colonialism, an aspect of the capitalist economic globalisation, had from its beginnings a genocidal tendency”, and that, from the colonial period through the 21st century, US policy has “entailed torture, terror, sexual abuse, massacres, systematic military occupations, removals of Indigenous peoples from their ancestral territories, and removals of Indigenous children to military-like boarding schools”.

None of this history has, however, prevented the US from selectively appropriating and mutilating aspects of indigenous identity – preferably ones that can be commodified in accordance with capitalist culture and thereby controlled. It is thanks to this arrangement that we’ve been graced with, for example, US football teams named the Redskins and the Seminoles, along with sports fans who gleefully perform the “tomahawk chop“.

The indigenous population, on the other hand, continues to have little to cheer about. In November 2017, CNN reported on data from the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention indicating that “Native Americans are killed in police encounters at a higher rate than any other racial or ethnic group”. And yet, in the vast majority of these instances, the US media is nowhere to be seen.

A special investigation in 2016 by In These Times magazine delved into the details of some of the cases, including the police murders of Jacqueline Salyers, a pregnant 32-year-old member of the Puyallup tribe, and Loreal Tsingine, a diminutive Navajo woman brandishing a small pair of scissors.

And then, there are those Native Americans who somehow perish in police custody. In These Times highlights the circumstances of the August 2015 death of Alaska Native Joseph Murphy – incidentally a veteran of the US war on Iraq – who “died of a heart attack in a holding cell in Juneau … as jail staff yelled ‘f**k you’ and ‘I don’t care’ in response to his pleas”.

Sick society

As it turns out, indigenous persons with mental illness are heavily represented among police-induced fatalities – including persons who were merely threatening to kill themselves prior to being eliminated by police.

And while many analysts cite the notorious dearth of mental health services in Native American communities, it seems that mental anguish is a rather logical outcome of several hundred years of oppression and trauma. In the meantime, a police force that murders suicidal people is a pretty clear indication of a sick society.

Enter current US President Donald Trump, who has capably taken over the reins of the ongoing US war on Native Americans while also referring in typical politically correct fashion to Senator Elizabeth Warren as “Pocahontas“.

In fact, Trump’s intersection with the indigenous question dates back until at least 1993, when he testified before Congress regarding certain Native American competitors in the casino business: “They don’t look like Indians to me.”

So much for revitalising indigenous identity.

Last year, Trump’s Columbus Day proclamation explicitly excluded any mention of Native Americans, who, of course, had nothing to do with the man who helped set the whole genocidal ball in motion.

This year, a Politico article quoted Mary Smith – former acting head of the Indian Health Service under Barack Obama – on punitive Trump-inflicted reforms that could forcibly require Native recipients of Medicaid to procure employment, despite traditional exemption from such requirements and a frequent dearth of job opportunities on reservations.

Native Americans, she said, had already “paid through land and massacres – and now you’re going to take away healthcare and add a work requirement?”

Battered landscape

The list goes on.

In May 2018, the Los Angeles Times catalogued additional assaults on tribal communities, such as the Trump administration’s “move to scrap federal rules mandating a thorough cleanup” of environmental contaminants affecting Native lands. One example: the Moapa River Indian Reservation near Las Vegas, where residents contend that “discarded toxic ash blowing from [a] recently shuttered coal plant” is to blame for rampant illness and premature death.

The battered US landscape hardly breeds optimism, given the compounding effects of Trump’s fossil fuel obsession, government salivation over the prospect of wrecking national parks and monuments, and the fact that, as the LA Times notes, “the return of hundreds of thousands of acres of land to tribal control – which had been proceeding apace under the last administration – has come to a near halt.”

And yet, life goes on, for the moment. In her Indigenous Peoples’ History, Dunbar-Ortiz writes that, while the understanding of genocidal US manoeuvres against Native Americans is “too often accompanied by an assumption of disappearance”, the reality of indigenous survival must not be overlooked: “Surviving genocide, by whatever means, is resistance”.

Given the current course of planetary meltdown, some lessons in resistance would no doubt come in handy – especially from human populations that managed to exist symbiotically with the Earth without destroying it.

But a one-day discussion of how to “encourage the protection of [indigenous] rights” is obviously not enough.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.