Obama won’t end the drone war, but Pakistan might

Drone strikes in Pakistan and other countries is not in the US national interest, and mires the country in endless war.

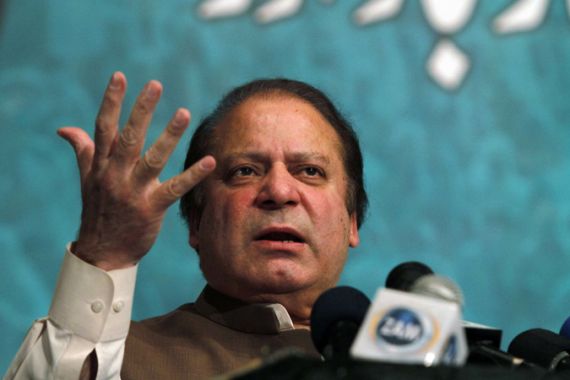

On June 7, the CIA launched a drone strike in Mangroti, North Waziristan, killing nine people. Days earlier, taking oath as Pakistan’s new prime minister, Nawaz Sharif had asked the US to respect his country’s sovereignty and refrain from further attacks.

The subsequent bombing can only be seen as a calculated insult. The newly elected government issued an angry demarche, condemning the attack. There has not been another attack since. How resolute Sharif proves in his opposition will determine the fate of the drone war.

The US can, of course, ignore Pakistani objections and continue bombing its territory. But beyond satisfying its revanchist fury, it can expect to gain little. It may, however, damage its own political options. Perhaps, as in the past, the US is trying to sabotage Pakistani attempts to negotiate peace with the Taliban, an avowed goal of the Sharif government.

It has certainly succeeded in diminishing the Taliban’s willingness to negotiate by making the new government appear weak, unable to protect its own sovereignty. But at a time when the US is itself negotiating with the Taliban, it makes little sense to damage the credibility of one government that can facilitate its exit from Afghanistan.

It is unlikely that the US State Department would have approved of these attacks. Its executor, the CIA, was likely also its author. The global “war on terror” has been a boon for the CIA. Under Bush, the agency regained the licence to kill that it had lost in the mid-1970s following the Church Committee investigations; Obama expanded and formalised this paramilitary function.

In the months after 9/11, Bush had infuriated Donald Rumsfeld by granting the CIA charge of the war in Afghanistan; the defence secretary in turn expanded the Pentagon’s intelligence gathering functions. Under Obama the two tendencies have been reconciled to the CIA’s advantage.

Perpetual war

The Obama administration has manoeuvered around the restrictions on the use of military force outside declared war zones by putting Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC) forces temporarily under CIA command, using the agency’s “Title 50” authority to operate globally. This authority was granted to the CIA with purely intelligence gathering activities in mind; Obama has used it to sanction lethal military operations from Pakistan to Yemen to Somalia.

|

|

| Inside Story Americas – Obama’s speech: The question of drones |

The CIA and the Pentagon have dwarfed the State Department in both resources and influence. In The Way of the Knife (2013), an important investigation into the evolution of the Obama administration’s counterterrorism policies, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Mark Mazzetti notes the political convenience of using the secretive CIA as the president’s preferred foreign policy tool. This affinity has in turn allowed the agency to exert influence over foreign affairs that exceeds that of diplomats.

Mazzetti relates instances where, at cabinet meetings, Panetta as CIA director was able to overrule Hillary Clinton, then the secretary of state, and her ambassador in Islamabad without demurral from Barack Obama.

The CIA is likely to resist any shift in policy that mandates relinquishing such power. But unless the conflict between the CIA’s institutional imperatives and US national interest is resolved, blood will continue to spill and the world will grow more dangerous.

This unresolved tension is also manifest in the ambivalence of presidential rhetoric. Last month, Obama laid out his new national security strategy in a magnificent soliloquy. But in aiming for Hamlet, Obama delivered Gollum.

Violence was undesirable, but he would continue using it; perpetual war was unwise, but his would continue indefinitely; America was at a crossroads, but he would maintain the current course; fear must not be the basis of policy, but his are based on a frightful catalogue of potential threats; the “total defeat of terror” was impossible, but he would not relent until he had finished the work of “defeating al-Qaeda and its associated forces”.

Obama exhorted Americans to ask “hard questions”, but answered with comforting bromides. He pronounced himself “troubled” by the stifling of investigative journalism, but offered its cause as remedy: his own Justice Department.

He eloquently denounced the monstrosity that is Guantanamo, but incredibly denied what Mazzetti, and Daniel Klaidman in his book Kill or Capture (2012), have revealed: that the Obama administration has dealt with the complications of capturing and detaining terrorism suspects by ordering them killed instead.

Some quarters hailed Obama’s speech as a step back from the militarist excess of his predecessor. The acknowledgments of error and the performance of anguish were meant to emphasise this break. But the speech offered little redress. The hope that it appeared to offer was abridged in action.

‘Signature strikes’

The only concrete proposal, a restrictive targeting criteria codified in a Presidential Policy Guidance, which in principle should have ended “signature strikes”, was quickly undermined by administration officials who told the press that the attacks would continue regardless. It also nullified Obama’s claim that a “high threshold” had been set for lethal action against “potential terrorist targets, regardless of whether or not they are American citizens”. Far from reassuring non-Americans, it should alarm US citizens.

But there was also a true statement in Obama’s speech. “America cannot take strikes wherever we choose,” he said. “Our actions are bound by consultations with partners, and respect for state sovereignty.”

The drone war will not end by a presidential epiphany. It will need political pressure and practical obstacles to stop it – mostly outside the US. Few Democrats are willing to criticise Obama, and Republicans rarely shrink from actions that result in dead foreigners; as long as the war’s cost are borne by others, it is unlikely that a critical mass of opinion would emerge to force a reconsideration of policy.

But unlike Americans, citizens in the targeted states are directly exposed to the war’s blowback. The need to pressure their governments into withholding cooperation with the drone war is more urgent. Only resistance in the targeted states can force Washington to stand down.

There is a precedent for this. The US launched its very first drone strike in Yemen in 2002. The strike was carried out with the cooperation of the Yemeni government with the understanding that, in order to avoid fraught questions of jurisdiction and legality, Yemen would take responsibility for it.

The charade soon fell through however when, during a television interview, Paul Wolfowitz, then the deputy defence secretary, claimed the assassination as a US achievement. Slighted and humiliated, Ali Abdullah Saleh, then the president of Yemen, angrily refused the US permission to carry out further attacks as long as Bush remained in office.

The varying intensity of attacks in Pakistan also suggests the degree to which they have been enabled by its governments. Between June 2004, when the first drone struck Pakistan; and August 2008, when Pervez Musharraf stepped down as president, there were a total of 17 attacks.

But the war escalated sharply once the pliant Asif Ali Zardari assumed office: a total of 351 attacks, including many “signature strikes”, were launched during his tenure. It appeared Zardari had granted the US the carte blanche that his successor had withheld.

Zardari was forced to reconsider cooperation only after tensions emerged between the US and the Pakistani military in 2011. Meanwhile in Yemen, as the Saleh government was weakened by protests, attacks escalated. Their numbers dropped only after stability returned.

The drone war can only proceed as long as targeted states acquiesce in it or are too weak to resist. Strong governments that have popular legitimacy can prove barriers. This month’s strike in Pakistan was the CIA’s attempt to forestall this possibility by forcing upon the new government an onerous choice: to lose favour with Washington by resisting or lose credibility at home by remaining silent.

|

|

| Discussing Pakistan’s role in Taliban peace talks |

Pakistan’s last two governments dealt with this dilemma by protesting in public while approving the attacks in private. Thanks to WikiLeaks, the public knows.

Political solutions

Nawaz Sharif can only maintain legitimacy – and the independence necessary for finding political solutions to Pakistan’s security problems – as long as he remains firm and, should the attacks continue, backs his words with credible measures, such as referring the case to the International Court of Justice or blocking the passage of NATO convoys.

In his national security speech, Obama claimed that he was acting within law, though the only law he cited was the Bush-era Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF). Obama claimed self-defence as the rationale and, like his predecessor, cited 9/11 as the justification. This reasoning was anticipated and dismissed by Christof Heyns, the UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial killings, summary or arbitrary executions.

“It’s difficult to see how any killings carried out in 2012 can be justified as in response to [events] in 2001,” Heyns told an ACLU gathering last year. “Some states seem to want to invent new laws to justify new practices.”

Equally disingenuous was Obama’s claim that drone attacks were preferable because putting boots on the ground would cause greater casualties. Indeed, for that very reason the US has been using drones in places where it would not dare setting American feet. “The collateral damage [from drones] may be less than aerial bombardment,” Heyns observed, “but because they eliminate the risk to soldiers they can be used more often.”

If more states were to arrogate to themselves the right to intervene globally using domestic law as sanction, the consequences would be dire indeed. That is why Heyns’ fellow UN rapporteur, Ben Emmerson QC, has described each drone strike as an attack on the system of “international law itself”.

Ian Seiderman, director of the International Commission of Jurists, has also echoed the sentiment in decrying the “immense damage… being done to the fabric of international law”.

But such niceties rarely detain the prosecutors of shadow wars. Indeed, in an interview with Mazzetti, former CIA operative Duane Clarridge pronounced the Treaty of Westphalia dead. This founding document of the international order established state sovereignty as an inviolable principle of international affairs.

The CIA has good reason to wish it dead; the US president has been acting as if it is already. But for all the assaults on its health, the Westphalian system retains much of its vitality. Powerful states have always used international law as a tool to be used where they can and ignored where they must. But they can do it only insofar as subordinate states are willing to forego their own rights.

There is no such thing as absolute power in international affairs; insignificant actors have often humbled superpowers. Pakistan is not insignificant and it has leverage over the US in the shape of NATO supply routes. It has no excuse not to assert its sovereignty.

The US might resent this. It will certainly infuriate the CIA, but at the end of the day, it can only bolster the need for diplomacy. It may even provide the US the cover it needs for a dignified retreat from Afghanistan. Otherwise, all three states will remain mired in a perpetual war that they all know will prove ruinous.

Muhammad Idrees Ahmad is a Glasgow-based sociologist with a specialisation in US foreign policy. His The Road to Jerusalem: American Neoconservatism and the Iraq War will be published by the Edinburgh University Press. He edits Pulsemedia.org.

Follow him on Twitter: @im_pulse