Battling superbugs: Cave bacteria could hold the answer

Scientists are searching underground in Canada’s Rocky Mountains for alternatives to cure infectious bacteria.

Sometimes you find what you are looking for in the unlikeliest of places. Canadian microbiologist Naowarat (Ann) Cheeptham certainly does.

She is a leading researcher into how best to battle a growing number of antibiotic-resistant superbugs, and she is looking for answers everywhere – from deep subterranean caves to the local sewage treatment plant in her hometown of Kamloops, British Columbia.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsGaza lost much more than a hospital when it lost al-Shifa

With measles on the rise, rebuilding trust in vaccines is a must

Could a bird flu pandemic spread to humans?

Cheeptham’s most recent breakthrough came after she met one of Canada’s top cave explorers: Nick Vieira.

Naturally enough, Vieira spends a lot of time underground – often kilometres deep in twisted caverns cut off from the surface by underground rivers and artesian wells.

The soil and dirt he finds in those subterranean nooks are fuelling Cheeptham’s search for treatments to kill superbugs.

“We find microbes in that soil,” she says. “Pristine organisms that haven’t contacted surface life in any way. When we put them in contact with drug resistance bacteria, we get fascinating results.”

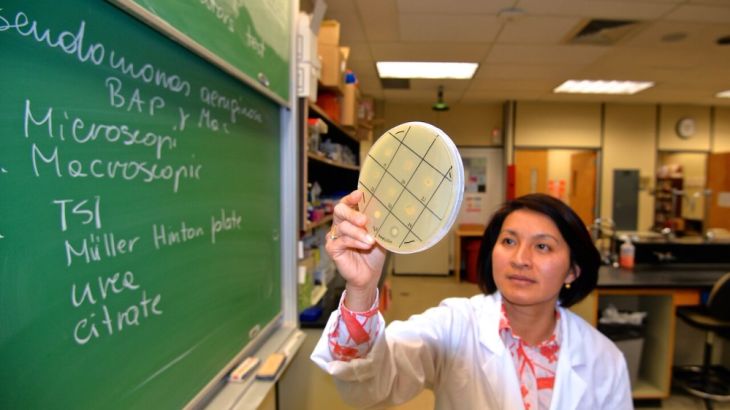

![Leading researcher Ann Cheeptham in her lab at Thompson River University [Jet Belgraver/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/2608a9593ae944698b6473abbd139f04_18.jpeg)

New drugs

The discovery of penicillin in 1928 sparked a revolution in medicine.

Bacterial infection, a leading cause of death, could suddenly be prevented with a simple drug. Antibiotics followed, attacking harmful microbes even more effectively.

But now many of these bacteria have evolved defences against existing drugs, while the search for their replacements has not been going well – thousands die every year from infections that used to be treatable.

Meanwhile, pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to spend money developing new antibiotics that might not earn as much in the market as Viagra or anti-cholesterol statins.

![The cave soil collected by Nick Vieira is helping scientists' search for treatments to kill superbugs [Jet Belgraver/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/e4b593a6e9104cf69d4f7b69463e0ca3_18.jpeg)

‘Last frontier’

In her lab at Kamloops’ Thompson River University, Cheeptham and her research assistants hold up petri dishes against a light table. They point at circular patterns surrounded by clear fluid.

“That’s where the cave bacteria are killing the superbugs,” Cheeptham says. “It’s very promising.”

Vieira is happy that his efforts are producing promise in the lab.

“It’s a whole, undiscovered world down there,” he says, standing beneath a cliff-side cave mouth near Canmore, Alberta, in the Canadian Rocky Mountains.

“It’s the last frontier on the planet – under the planet – and working with scientists helps you to discover so much about it,” adds Vieira, who is now delivering bags of cave soil to microbiologists in the United States as well.

In a video on his website, he and a colleague scrape dirt from the sides of a Rocky Mountain cave called Raspberry Rising, where most of the best samples have come from.

In his waterproof cave suit and head lamp, Vieira is visibly gleeful as he fills a plastic bag with clay.

“High-school science, I hated it, but here I am. Who’d have ever thought I’d be learning so much about the world,” he says, his words echoing off the stone walls.

![Student Emma Persad gets a water sample from the sewage treatment plant in Kamloops [Jet Belgraver/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/d81ba822e37f4201a99a77f2eb48f779_18.jpeg)

In the name of saving lives

Back on the surface, the search takes another direction.

Cheeptham and her undergraduate student, Emma Persad, are delving into medical history as they plumb the sewage lagoon of a Kamloops water treatment plant – in the vials of murky water, there is quite possibly another option to defeat superbugs.

Bacteriophages, also known as phages, are a type of virus with one essential quality: they are deadly to certain forms of bacteria.

Phages were discovered by researchers in France and England during World War I and they became a preferred form of treatment for infection in the former USSR and its satellite countries in Eastern Europe. They are still in use in those areas today.

But thanks to the discovery of antibiotics, which are easier to use and affect more species of bacteria, phages fell out of favour elsewhere.

Persad and Cheeptham are determined to change that. They are working together to convince North Americans and Western Europeans that human and animal waste contains life-saving qualities.

Persad says they are battling Western prejudice, not science, because the effectiveness of phages is well known already.

“In North America, we just don’t like the word ‘virus’,” she says. “We don’t like to think about putting a virus into ourselves to fight a bacterial infection.

“Antibiotics affect all bacteria. They kill even good bacteria in the body but if you use specific bacteriophages then only the bad bacteria, those causing illness, are killed. The good bacteria – in your stomach and intestines – aren’t affected at all.”

Best of all, because phages are a form of virus, there can be no resistance to them.

“All that’s holding us back is our own reluctance,” Persad says.

To Cheeptham, it is all a matter of having as many medical options as possible to save lives.

“I believe that we still need to widen our toolbox – if you think of antibiotics [as being] in a toolbox, we are running out of tools and we need to fill this box. And where should we go to find this? Anywhere we have to.”

Whether it is thousands of metres underground, or in the pungent shores of a sewage lagoon, it is all in the name of saving lives.