Q&A: ‘Why violence has declined’ among humans

Steven Pinker, author of “The Better Angels of Our Nature”, argues this may be the most peaceful era in human existence.

|

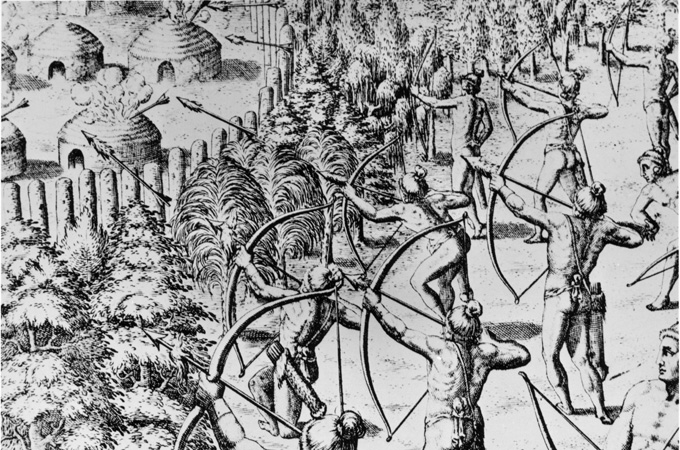

| Pinker argues that overall levels of violence in tribal, hunter-gatherer societies were much higher [GALLO/GETTY] |

Despite the seemingly endless stream of news stories focusing on violence, crime and death that are splashed across the world’s front pages, humans are now living in one of the most peaceful periods of our existence. That’s according to a new book by Steven Pinker, a Harvard Psychology professor and one of the “World’s Top 100 Public Intellectuals” according to Time magazine.

The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined, published in 2011, discusses the various transitions in human history that led to more peaceful societies. One of the most influential transitions was the move from hunter-gatherer societies to organised states – a process Pinker refers to as “the pacification process”.

That transition led to a major decrease in violence because the state stepped in during conflicts as the arbiter of “justice” as opposed to the tribal process of retaliatory attacks and revenge murders, he argues.

“The civlising process”, describes the decline of violence in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. As Pinker puts it, “a contemporary Englishman has a 50-fold less chance of being murdered than his compatriot in the Middle Ages”.

Critics of Pinker’s historical argument say he focuses too much on Western Europe, while generally ignoring trends of violence in Asia, Africa or South America, allowing the psychologist to “gloss over” other episodes that don’t fit into his narrative.

To that, Pinker would most likely answer that the downward trend in violence has not necessarily been smooth, but nonetheles it has “gone bumpily, but dramatically, down”.

Were things really so much worse 5,000 years ago?

Before the spread of settled agricultural civilisations and governments, starting around 5,000 years ago, feuding was a recurring feature of people’s lives, and they had to worry about raids in which an enemy village or tribe would shoot the men with arrows or spears and abduct the women as wives.

Many sources of evidence testify to the violence of non-state life, including forensic analyses of violent trauma on skeletons, the prevalence of fortifications and shock weapons and contemporary estimates of rates of violence among the last surviving peoples living in anarchy – namely hunter-gatherer and hunter-horticultural bands and tribes.

What did the transition from tribal life to kingdoms, empires and now states have to do with the decline in violence?

The first kings and emperors did not have a benevolent interest in the welfare of their subjects. Instead, tribal raiding and feuding were a nuisance to imperial overlords – who would just as soon keep the people alive to provide them with soldiers, taxes and slaves.

How do you explain the genocides and mass murders of the 20th century within the context of a decline in violence? What indications do we have that another Hitler, Stalin, Mao won’t find a similar way to slaughter millions?

There were plenty of genocides and mass murders in other centuries as well, and as a proportion of the population, they did comparable damage. World War II was certainly the worst event in human history, but it was not part of a trend of increasingly destructive wars – on the contrary, the rate of death in warfare has gone bumpily, but dramatically, down since 1946.

As for genocidal maniacs, there is no guarantee that another one won’t arise, but it’s far harder for a Mao or a Stalin to commit genocides within a democracy, and the world has far more democracies now – indeed, more than it has autocracies.

|

“Ideologies, particularly ones that demonise some group of people as the only thing standing in the way of utopia are the causes of the most murderous events in human history.“ |

How do the numbers of people killed from so-called terrorism compare with those killed from homicide, war or genocide?

There’s no comparison. 9/11 was the worst terrorist attack in history, and it killed fewer than 3,000 people, which is a fraction of those killed in most wars, genocides or homicides.

Other than the prospect of nuclear terrorism, terrorism seeks to work by the fear it causes – the “terror” in terrorism – rather than by the damage it does. In any case, terrorism is a provably stupid tactic – 97 per cent of terrorist movements fail to attain any of their strategic objectives.

Israel has taken Ahmadinejad’s apparent wish to “wipe Israel off the map” as an existential threat, and in return has threatened war. Do you see any likelihood of Iran using nuclear weapons, if it were to acquire them, against Israel?

I think it is extremely unlikely that [President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad will attack Israel with nuclear weapons. On the other hand, the Israelis are not crazy to worry about a low-probability yet catastrophic possibility, and Ahmadinejad’s destructive fantasy, together with his other reckless statements (such as denying the Holocaust), are cause for legitimate worry. Calling for the destruction of a member state of the United Nations is extraordinarily provocative – no member state of the UN has ever gone out of existence through the use of force.

What is the connection between ideology and mass atrocities?

Ideologies, particularly ones that demonise some group of people as the only thing standing in the way of utopia (heretics, infidels, the bourgeoisie, Jews, Tutsis, rich peasants) are the causes of the most murderous events in human history.

Such belief systems justify violence by a toxic means – ends analysis: If a Messianic Age will be infinitely good, then any amount of violence may be perpetrated to attain it, and those who oppose it are infinitely evil and deserving of arbitrarily harsh punishment.

What is the relation between what you consider a general decline in violence and the increased attention and protection of children, ethnic minorities, women, and homosexuals in some societies?

The rights revolutions that have protected these vulnerable groups against lynching, rape, domestic violence, gay-bashing, physical and sexual abuse, harsh physical punishments and cruel practices have been driven, I believe, by the same repugnance to violence, driven by the same humanitarian concerns.

In terms of psychology, is there an innate drive towards violence and aggression within us? Or conversely, an innate drive to be “good”?

Neither and both. Humans harbour a number of distinct motives that can result in violence: including greed, vengeance, dominance, sadism and destructive ideologies. They also harbour a number of distinct motives that can inhibit violence – what [US president Abraham] Lincoln called “the better angels of our nature”: including self-control, empathy, reason and a sense of fairness.

The amount of violence in a society depends on which of these motives prevail.

What does international trade/commerce have to do with the decline of violence?

In general, societies that engage in trade and are open to the world’s economy have lower rates of interstate war, civil war and genocide. This is consistent with the Enlightenment theory of “gentle commerce” and the evolutionary theory of “reciprocal altruism” – it’s better for both sides if one tries to get ahead by trading things rather than by stealing them.

How would our collective psychology be affected if we knew that we are living in a relatively peaceful era of human history?

We could try to identify the causes that brought violence down – including commerce, democracy, cosmopolitanism, education, good government, sound institutions and freedom of speech – and try to implement them widely and robustly.