In Pictures

‘Swimming with dead bodies’: A year on, Greeks haunted by inferno

On anniversary of Greece’s worst natural disaster, Mati residents express frustration with pace of recovery.

Mati, Greece – Yorgos Asimakos ran into the sea in his clothes and shoes. His son, Nikos, was right beside him, and was the one who moments earlier had saved him by guiding him down a narrow flight of stairs that led to the beach.

“There was black smoke everywhere and I panicked, I didn’t know where to go,” recalls Asimakos, 62. “Nikos was to my right but I lost sight of him so I shouted, ‘Don’t leave me’; if he hadn’t returned, I’d be dead.”

Asimakos and his then-23-year-old son were fleeing a wildfire, which on July 23, 2018, engulfed Mati, a popular seaside resort east of Greece‘s capital, Athens. Driven by gale-force winds and fuelled by omnipresent pine trees, the rapidly-spreading blaze caught many locals and holidaymakers off guard. For some, the only way to safety was to run towards the sea.

“I stayed in the water for four-and-a-half hours,” Asimakos says. “A black cloud was above us and we couldn’t breathe,” he adds. “I saw female neighbours of mine naked, their clothes burned, and being in pain for hours inside the sea.”

But many had not made it that far.

Amid the frenzy to escape, panicky drivers clogged the streets leading away from the poorly planned town. Many were trapped in their cars. Others died in their homes or were overtaken by the advancing flames and smoke as they dashed to reach the sea, including some who were found huddled together, their path to the beach blocked by a cliff after making a wrong turn.

“There was chaos everywhere; people were running and cars were crashing,” says Yiannis Stampelos, whose family-owned restaurant is in one of the very few easily accessible seaside spots in Mati and became a haven for hundreds in the area.

But making it to the sea did not guarantee safety, either. People, among them many elderly, remained stranded for several hours with no help, and several drowned.

Asimakos says while in the water he could constantly hear explosions but had to turn his back to the coast due to the blazing heat. It was only hours later, after returning onshore, that the full scale of the disaster would become apparent to him.

“Fires were simmering everywhere, and the roads were full of wires, full of cars and full of bodies,” he says. “In one car, there were three little children burned to death, melted.”

Later on, he found his sister-in-law, Vicky, lying motionless on the ground near a multi-storey apartment bloc. “She wasn’t burned to death; the toxic fumes filled her insides, poor woman.”

‘Impossible to convey’

Overall, the devastating blaze a year ago caused the deaths of 102 people, the highest recorded toll from a fire in Greece’s modern history. It ravaged some 5,600 hectares of land, destroyed thousands of buildings and left dozens suffering from burns.

One year on, along with the questions about how such a tragedy occurred, residents are frustrated with the slow pace of recovery.

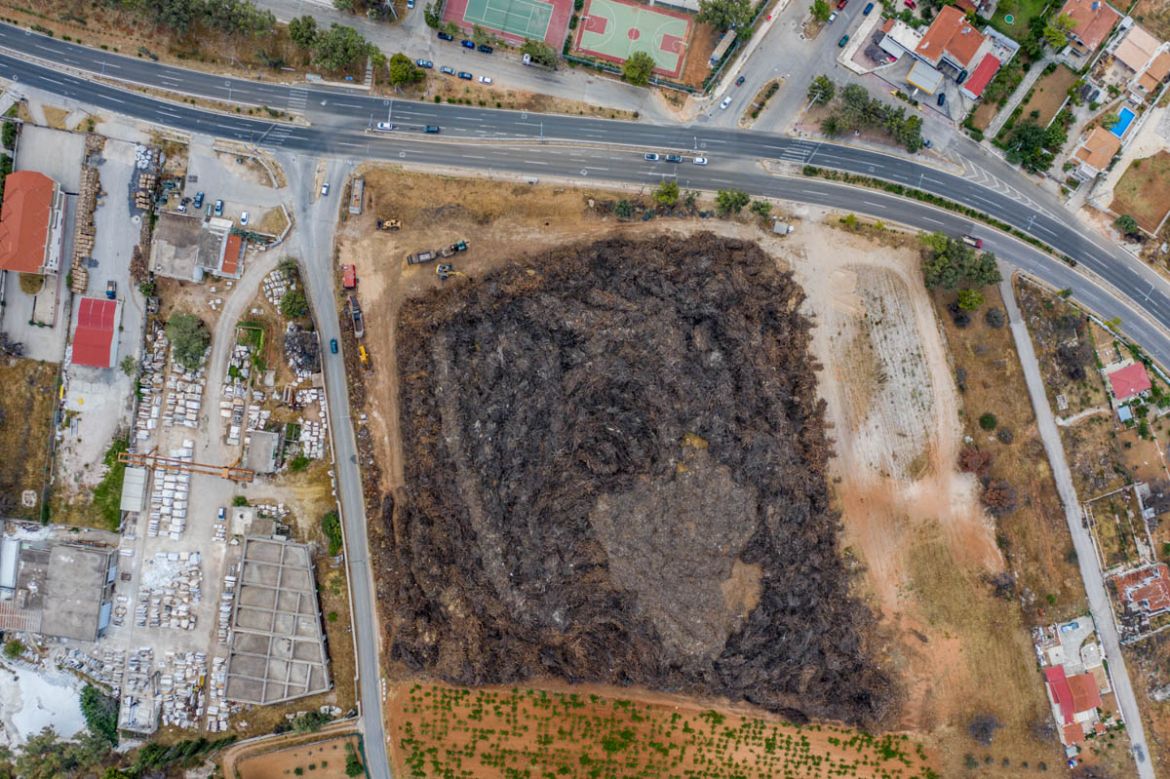

Locals say the clean-up operation is months behind schedule and warn that a bulky mass of burned branches and trunks collected from the area is a major fire hazard, as are the stacks of dry grass and debris that can be seen on pavements and outside properties across the town.

Affected residents also call for the fast-tracking of processes to issue licences for the repair and reconstruction of the roughly 3,000 houses that were damaged in the fire.

The Greek government at the time, led by Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras of the left-wing Syriza party, blamed unlicensed building for the high number of casualties and sacked the chiefs of the police force and fire services, amid intense criticism over its response during the tragedy.

In March, prosecutors investigating the inferno issued a 293-page report detailing the lack of coordination among the authorities which resulted in “chaos and a collapse of the system, general liabilities of the competent services, and criminal mistakes and omissions in addressing the deadly fire”.

Prosecutors also said that many lives could have been saved “if civil protection measures had been activated to alert residents” of the approaching fire, while locals slammed police for diverting vehicles at one point in the direction of the blaze amid a communications breakdown with the fire service.

“Police allowed people to go towards Rafina [to the east of Athens], which was a big mistake and that’s when the big turmoil happened,” Agathe Kedikidi, a resident, says. “People got trapped [in their cars], they couldn’t move – couldn’t even open their doors.”

A 65-year-old man has been charged with arson, suspected of starting the blaze by allegedly burning wood outside his house in an area west of Mati.

In an emotionally charged ceremony on Sunday in memory of those who perished a year ago, Mihalis Chrisohoidis, minister of civil protection for Greece’s newly elected government, said there were still “open wounds” and said a number of issues still needed to be addressed, in areas including urban planning and healthcare.

Asimakos says the memories of the disaster still haunt him.

“Those who didn’t experience the fire are lucky,” he says. “My wife lost her sister, she’s crying every day and I’m not sure if she’ll ever get over it – but she was at work and didn’t go through what our son and I did,” he adds.

“We were swimming with dead bodies at sea … it’s impossible to convey what happened.”

![“They only thing they [authorities] do is to collect the rubbish, not the debris and the [burned and sewn-off] branches,” says Yorgos Asimakos. “Throughout the summer, when the temperature is 40 degre](/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/db21ec946e574075ba68c7a86c077405_8.jpeg?fit=1170%2C781&quality=80)