Cafe Yafa: A Palestinian bookshop reviving literary culture

Cafe Yafa continues a rich Palestinian literary culture, decades after the Nakba destroyed the libraries of Palestine.

Jaffa – “Jaffa will be a Jewish city … Allowing Arabs to return to Jaffa would not be righteousness but stupidity,” David Ben-Gurion wrote in his diary in June 1948.

Israel’s first prime minister, who arrived in Palestine at Jaffa port in 1910, was writing after right-wing Irgun forces razed Jaffa in April and expelled nearly 70,000 Palestinian residents.

Keep reading

list of 3 itemsRashida Tlaib pushes for Palestinian Nakba recognition in US

Nakba film streams on Netflix despite Israeli threats

After the bombs stopped, looting began: Ben-Gurion was one of the strongest supporters of the expropriation of Palestinian property. Months later, thousands of Arabic books lay on the streets, “badly damaged during the war … wind, rain and sun”, according to Adam Raz, historian and author of The Looting of Arab Property in the 1948 War.

The books came from public and private libraries, mosque and church collections, the reading rooms of Jaffa’s social clubs, and seven modern bookshops that lined Jaffa’s shopping district.

Arabic bookshops disappeared from Jaffa for 55 years, until Michel Raheb of Ramla first decided to open one in 2003. He decided Jaffa was the best city for it and Cafe Yafa opened its doors that same year.

Books in a ghetto

Raheb wants to share his love for books. Years earlier, in the 1990s, he had volunteered his time and personal collection of thousands of Arabic books to open a library in his local Ramla church.

He made Cafe Yafa into a community gathering spot, offering coffee and Arabic cuisine to Palestinian and Israeli guests who come to shop, snack, chat, and read.

For Palestinians who come from all over the country, Cafe Yafa is an essential space, as there are few Arabic bookshops anywhere in Israel and none south of Jaffa.

The profound loss of Palestine’s written heritage still lingers with many, who recall the words of Khalil Sakakini after his private library in Jerusalem was robbed: “Goodbye, my books! Farewell to the house of wisdom … How much midnight oil did I burn with you reading and writing, in the silence of the night while the people slept!

“Were you looted? Burned? … Did you find your way to the grocer, your pages wrapping onions?”

Bechor-Shalom Sheetrit, the first and last Israeli “minister of minorities”, was an unlikely and ersatz saviour of Palestine’s books.

A Jew of Moroccan descent and the only Sephardic Jew in Israel’s first cabinet, Sheetrit was responsible for the needs of the “minority population” of Palestinians, because he had experience in “Jewish-Arab” affairs and was a fluent Arabic speaker with ties to the Palestinian community.

According to an article by Israeli scholar Alisa Rubin Peled: “[Sheetrit] was … horrified when he saw what had happened to the Palestinian property, and especially the books … the Office of Minorities sent a truck full of Arabic-speaking Jews to Haifa, Ramla, Lydda, Beersheba, and other cities to preserve the books”.

About 80,000 books were collected and stored in warehouses to be sorted. By the war’s end, 4,500 books were moved to a three-storey building in Jaffa near the ghetto that the few thousand remaining Palestinians were forced into.

There, within sight of their pillaged homes that would soon be settled by 45,000 Jews, Palestinians were forced into a crowded ghetto in the Ajami neighbourhood for months, surrounded by barbed wire and cut off from the sea.

The books were never returned, with rare exceptions. Some are held to this day at the National Library of Israel in West Jerusalem where they are catalogued as “Abandoned Property”.

Cafe Yafa: The revival

As the typical Cafe Yafa day full of chatter and friends greeting each other winds down, the staff prepare for the evening’s activities, transforming the cafe into a cultural centre, offering Arabic language classes, concerts, film screenings and lectures.

A recent weeknight lecture on stopping the Israeli army’s planned demolition of Masafer Yatta in the South Hebron Hills, saw Cafe Yafa packed with guests sitting on the floor, hearing from a collection of lawyers and activists.

At times, during the week, the cafe is quiet with only the elegant voice of Fairuz in the background. When one steps outside, one can feel the gentle breeze of Jaffa’s sea, which is only blocks away.

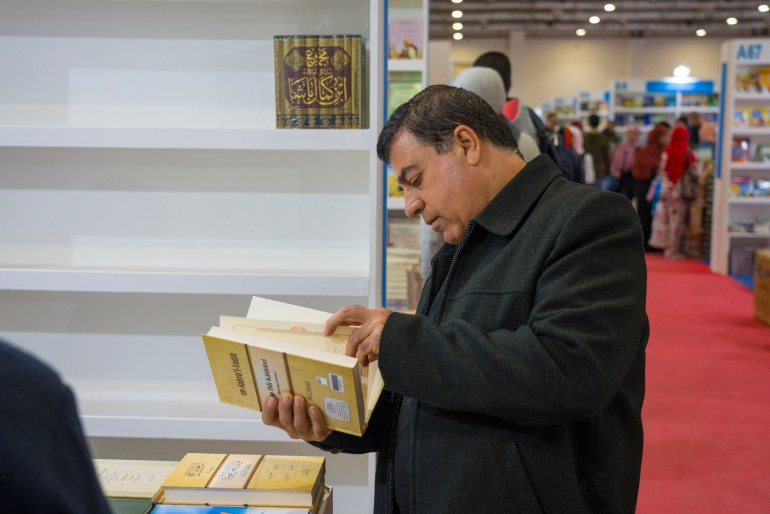

Perusing the bookshelves of Cafe Yafa opposite the kitchen, avid readers of Arabic literature are pleased that Raheb does not stock just the popular Arabic thrillers and romance novels flying off the shelves in Cairo and Beirut.

Rather, the shelves are loaded with books like the short stories of Gaza by Palestinian author Talal Abu Shawish, and collections of Palestinian poetry from notable poets like Mahmoud Darwish. Books teaching the Arabic language are also on the shelves.

Even if many Israeli customers do not read Arabic and are unlikely to ever buy a book, Raheb says: “It is important for me that Israelis see Arabic books.”

Managing an Arabic bookshop is not lucrative, something Palestinian owners feel just as much as bookshop owners around the world, but they have the additional burden of operating in a state that challenges their very existence.

Mahmoud Muna, owner of the Educational Bookshop in Jerusalem, explains that for many Palestinians living under occupation, “purchasing Arabic books is a luxury, not a necessity”. Raheb agrees, explaining that in times of increased national stress – such as the current moment – his business suffers.

On top of that, Israeli policies make selling Arabic books an even greater challenge. Saleh Abbas, owner of the Kull Shay bookshop in Haifa, received a letter from the Israeli government in 2008 telling him that his permit to import books published in “enemy states” such as Syria and Lebanon would be cancelled.

Such a ban covered approximately 80 percent of the Arabic books sold in Israel. These included school and university textbooks; the works of Darwish printed by Dar al-Awda in Beirut; and other translated works such as the Arabic translations of Harry Potter, Shakespeare and even Israeli authors such as Amos Oz.

While Abbas arranged a temporary settlement with the Israeli authorities, the British-era Trade With the Enemy Act of 1939 remains Israeli law today and is in effect for other importers of Arabic books.

Muna sees this law as among the reasons why “there is probably not a single Arabic bookshop in Palestine that can afford to sell only books”. His Educational Bookshop also includes a cafe in its English branch, while across the street the Arabic shop sells school and office supplies.

Raheb has made the 45-minute commute from Ramla to Jaffa for 20 years to run Cafe Yafa, and he has no plans to move.

“I love Jaffa and Haifa and Ramallah – but I was born in Ramla and I belong there. We, the Palestinians, have roots in the earth. It is hard for us to move around. If I moved to Jaffa after 20 years, and you asked me a few years later where I am from, I would always say Ramla.”

While the Nakba is often cast as a discrete historical event – referring to the expulsion and killing of Palestinians during the violence that ended with the establishment of Israel in 1948 – local Jaffa historian Abed Satel describes it as a continuous and ongoing process in his book, Jaffa: Letters in the Shadows of the Nakba.

“The Nakba is the march of a people that began before the occupation of Palestine and the ethnic cleansing of Jaffa [in 1948]. It continues … until the present day,” he writes.

Raheb is prepared to continue the struggle to resist the erasure of Palestinian literary culture and to sell Arabic and Palestinian books well into the future. He has a successor, his nephew Tony Copti, in line to continue the work.

He is even optimistic that “in another 20 years … there will be more Arabic bookshops”.