From Khalistan to tourism dollars: Pakistan’s love-hate ties with its Sikhs

How the separatist Khalistan movement paved the way for the preservation of Sikh gurdwaras in Pakistan.

In the complex of the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib Kartarpur, one of the most sacred Sikh places of worship in the world, an unexploded bomb is displayed in a glass case. Beside it, a sign states that the Indian air force dropped the bomb during the 1971 India-Pakistan war “with the aim to destroy” the gurdwara.

Located in the town of Kartarpur, Pakistan, just 4km (2.5 miles) from the border with India, the gurdwara, where Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism, spent his last years, was unharmed in the attack. This, the sign explains, was because the bomb landed in a sacred well.

Almost four decades later, in 2019, the two countries opened the Kartarpur corridor, a border crossing with visa-free access to Indian pilgrims wanting to visit the gurdwara, where Guru Nanak, died in 1539. Guru Nanak’s birth will be celebrated on the November full moon on Monday, November 27 this year.

The Sikh faith was founded in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent towards the end of the 15th century. Its followers found themselves divided between India and Pakistan during the 1947 Partition of India. The vast majority of Sikhs ended up in India, but many of Sikhism’s religious sites and a small Sikh minority remained in Pakistan, where during Sikh religious festivals attended by thousands of Indian pilgrims and Sikhs from other parts of the world, India-Pakistan antagonism continues to play out.

In many cases, this takes the form of support for a political movement that demands a separate Sikh homeland.

The Khalistan movement, which took hold in the 1970s, was potent in the 1980s and ’90s. While it has lost much of its momentum since, it has recently come under the spotlight again since the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Canadian Sikh leader and proponent of the movement, in Canada in June. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said three months later that Canadian security agencies had “credible allegations of a potential link” between Indian government agents and Nijjar’s shooting death.

During Sikh festivals in Pakistan, shirts with the message, “Never Forget 1984,” or images of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a leading figure in the Khalistan movement, are often sold.

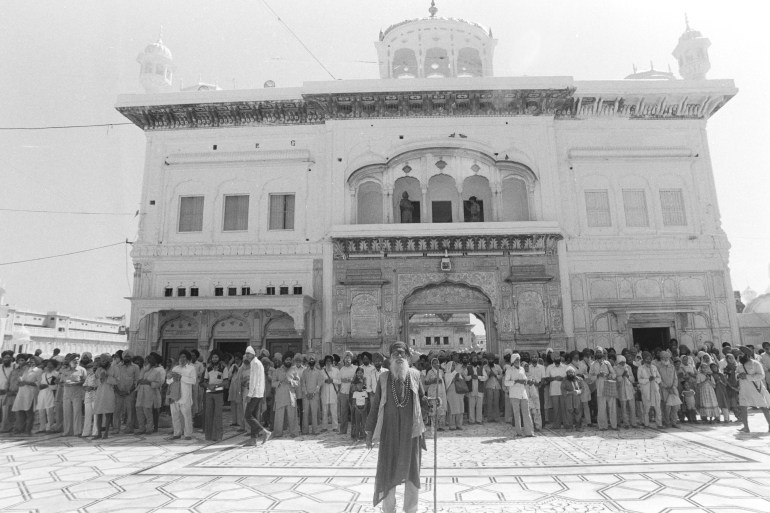

Bhindranwale became the face of Sikh revolutionary politics in the early 1980s. He was assassinated in June 1984 during Operation Blue Star, in which the Indian army entered the Golden Temple in Amritsar, Punjab, during a major religious event.

The operation damaged one of the holiest Sikh shrines and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of innocent civilians, who were at the gurdwara to commemorate the martyrdom of Sikhism’s fifth guru. It caused widespread anger in the Sikh community.

Later that year, Indira Gandhi, the prime minister of India, who had overseen the operation, was assassinated by her two Sikh bodyguards in retaliation. Immediately, anti-Sikh riots began in Delhi. Thousands of Sikhs were killed in just a few days.

Operation Blue Star and the anti-Sikh violence ushered in a new and much more violent phase of Sikh separatism and the demand for the establishment of Khalistan, a separate Sikh state.

Seeking revenge for India’s role in the 1971 war that led to the creation of Bangladesh, the Pakistani state came out in support of the Khalistan movement and was accused by India of providing a haven to its fighters – training them, providing them with weapons and supporting them financially. A byproduct of this support was a softening of Pakistan’s attitude towards its own Sikh community and its heritage.

From ‘long live Khalistan’ to preserving the gurdwaras

“In those days [the mid- and late 1980s], you would see banners [saying] ‘Khalistan Zindabad’ (‘Long Live Khalistan’) and pictures of Bhindranwale all over the gurdwara,” said Madan Singh*, a resident of Nankana Sahib, a city in Punjab, Pakistan.

Madan witnessed how the movement transformed the gurdwaras in Pakistan. Many expat proponents of it – Sikhs living in the United Kingdom, United States and Canada who couldn’t travel to India because of their political views – would come to Pakistan instead and speak to Indian pilgrims during religious gatherings.

He recalled a festival that took place in 1985 when the wounds of Operation Blue Star and the anti-Sikh riots of the year before were still fresh. Many powerful speeches were made in favour of Khalistan that year, including one by Sardar Ganga Singh Dhillon, a US-based supporter of a separate Sikh state who spoke vehemently against the Indian government, rousing the passion of many young Sikh men at the gathering and perhaps also aware that representatives of the Indian High Commission in Pakistan were in attendance.

Madan described how the crowd turned towards these two diplomats, who barely managed to escape the gurdwara. “The Pakistan state intervened,” he told me when I interviewed him for my book on Pakistan’s religious minorities, A White Trail, in 2011. “I was arrested along with 25 other people and was kept in jail for 10 days.”

While the Khalistan movement was transforming these gurdwaras into political spaces, it was also having another impact.

With almost the entire Sikh population of West Punjab (the area of Punjab that became part of Pakistan) having migrated to India at the time of partition in 1947, hundreds of Sikh gurdwaras had been abandoned.

These were some of the holiest shrines associated with the religion, but without the presence of the community – and with the indifference of the Pakistani state towards its non-Muslim heritage – most of these gurdwaras fell into disrepair. Some were converted into residences, schools or government buildings while others were completely lost. A few prominent ones, such as Gurdwara Janam Asthan at Nankana Sahib and Gurdwara Panja Sahib at Hassan Abdal, were looked after by one or two Sikh families who had either remained in what became Pakistan or come over from India just to look after these places of worship.

Places of worship – once again

During the heyday of the Khalistan movement, as prominent expat leaders from around the world came to Pakistan, leaders like Ganga Singh also took up the cause of renovation of these sacred spaces with the Pakistani state. During religious festivals, they would exhort the Sikh community living in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh provinces to come to Punjab and look after these shrines.

Many responded to their calls, including the family of Rajbir Singh* who moved to Nankana Sahib from Parachinar in 1978 after listening to a fiery speech there by Jagjit Singh Chauhan, another expat supporter of Khalistan.

Gradually during the late 1970s and ’80s, Sikh families from northwestern Pakistan began moving to Nankana Sahib and, over the years, a community began to develop in the city. This migration grew exponentially in the first decade of the 2000s as the Pakistani Taliban began to take over parts of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas and began demanding jizya, a tax for non-Muslims living in Muslim-controlled areas. Thousands moved to Nankana Sahib and other cities like Peshawar, where there were already Sikh communities.

Today, there is a thriving Sikh community of about 1,500 at Nankana Sahib, according to the latest census, ensuring that not just Gurdwara Janam Asthan but all the other gurdwaras of the city are being looked after and have become places of worship once again.

With Nankana Sahib being an important base for the community in Punjab, many Sikhs have also now moved to other cities in the province, ensuring that more gurdwaras are being reconverted into sacred spaces.

This process, through which the Sikh community is ensuring its presence around different gurdwaras in Pakistan, began with the Khalistan movement.

What was also pivotal in the redevelopment of these abandoned Sikh gurdwaras was the changing attitude of the Pakistani state towards Sikh heritage in the aftermath of the movement. While previously sceptical of “foreign money” coming into the country for the renovation of the gurdwaras, the state now facilitated transfers by the expat Sikh community to fund the renovation of these gurdwaras.

Local government officials were appointed to look after the security of these buildings while Sikh pilgrimages were arranged to these newly renovated gurdwaras, making it easier for the expat Sikhs to get visas to visit Pakistan. Through this process, several gurdwaras that had until then been abandoned and were lying in ruins were renovated, and the local Sikh community was encouraged to come and stay at these places.

Gurdwara Sacha Sauda at Farooqabad, Gurdwara Bhai Biba Singh in Peshawar, Gurdwara Bairi Sahib in Sialkot, Gurdwara Shaheed Gunj in Lahore and Gurdwara Dera Sahib at Kartarpur are just a few examples of the gurdwaras that have been renovated and opened for Sikh pilgrims over the past four decades.

“There was a fundamental shift in 1999,” said Kalyan Singh, assistant professor at Government College University in Lahore. Originally from the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, Kalyan’s family moved to Nankana Sahib in the 1970s. He was the first Pakistani Sikh to be awarded a doctorate.

“The Pakistani state realised that millions of rupees were being presented to these gurdwaras in the form of donations from pilgrims. All of this money was being taken back to India by the Sikh Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee [SGPC].”

The SGPC is an Amritsar-based organisation responsible for the administration of Sikh gurdwaras in the Indian states of Punjab and Himachal Pradesh and the union territory of Chandigarh. “The Pakistan Sikh Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee was formed in 1999 to ensure that the offerings presented to the gurdwaras were kept within Pakistan,” Kalyan said.

Gurdwaras – ‘low-hanging fruit’

The initial renovation of these gurdwaras – facilitated by the Pakistani state, sometimes through direct support and at other times by making it easier for the expat Sikh community and organisations to send money into the country – may have taken place to appease the expat Sikh community, which supported the Khalistan movement over the years.

But it also became increasingly clear to the state that there was a real tourist opportunity associated with these gurdwaras. This became particularly apparent after the opening of the Kartarpur corridor in 2019, from which a new local economy has emerged around Sikh religious tourism in Pakistan with several tourist companies specialising in this form of travel.

“The policymakers in Pakistan see Sikh tourism as a low-hanging fruit,” said Jahandad Khan, founder of the Indus Heritage Club, a tour-operating company that specialises in Sikh tours in Pakistan. “There exists a global Sikh diaspora that doesn’t require a lot of marketing relative to other communities to visit Pakistan. The government of Pakistan recognises the tourism opportunity in that.”

With the Khalistan movement in many ways irrelevant today, it is this economic imperative that now shapes the government’s relationship with these gurdwaras, especially as its economic struggles worsen.

While the Kartarpur corridor has still not achieved its anticipated economic potential due to COVID-19 and the strained India-Pakistan relationship, Pakistan estimated it generates $36.5m per year just from tourism to this one gurdwara. “The volume of Sikh tourism in Pakistan is too tiny [at this point] to make any meaningful transformation in this country,” Jahandad said. However, given the focus of the state, Pakistan hopes to expand Sikh tourism exponentially in the coming years, bringing in much-needed dollars to a struggling economy.

More than three decades since the heyday of the Khalistan movement, its ripple effects are still being felt in the country. The movement helped to shed light on the Sikh community and gurdwaras of Pakistan and forced the country to re-examine its relationship with this heritage. Finally, it also made Pakistan realise that there is so much more the country can gain economically from renovating and opening up these gurdwaras than it previously imagined.

*Some names have been changed to protect identities.