The financial burden of weddings on India’s poorest families

A culture of extravagance and exploitative practices force brides’ families to spend beyond their means – but change could be under way.

New Delhi, India – New Delhi-based schoolteacher Sunita Sharma was very excited about her wedding in November 2019 to her neighbour, an electrician. The 26-year-old had saved up $2,000 from her monthly salary of $200 for the wedding expenses.

But that was not enough. Her mother also had to sell off the family’s small piece of land to buy her only daughter a trousseau – furniture, a television and a refrigerator. The rest of the money went into booking a small wedding hall, hiring a local music band and catering for a party of 200 guests.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsCoronavirus: How an Indian wedding and funeral infected 100

India police stop interfaith marriage citing ‘love jihad’ law

Two Weddings, Somali Style

However, a last-minute demand from her fiancé’s father sent the Sharmas into a panic. He wanted his son to be given a car as well. Sunita pleaded that a car would be out of their budget as they had already exhausted all their funds. Besides, her father had died when she was 19 and so, as the oldest of four, she had worked very hard to feed her family.

But the groom’s family would have none of it. “My fiancé said that if the wedding was to be formalised, the car’s precondition would have to be met. Ultimately, the wedding was called off,” says Sunita.

Though she has since married and moved on, Sharma’s harrowing experience mirrors that of millions of Indians, and it is a plight that affects poor and lower-middle-class families most severely.

The Indian wedding – colourful and cacophonous – is an occasion often marked by hundreds, if not thousands, of guests, lavish banquets and venues and brides and grooms kitted out in eye-popping costumes and jewellery. Some 10 million weddings take place each year in a market worth $50bn. But the occasion also puts enormous social pressure on the bride’s family to spend vast sums of money in order to fulfil the demands of the groom’s family and impress relatives.

Failure to do so can have ramifications. The marriage may be called off, or the family may end up borrowing from informal moneylenders, a common practice as many in India still rely on cash and not bank transactions. These loans can come at an astronomical interest rate, indebting the family for life. Weddings that have been called off have driven brides and their parents to commit suicide due to fear of social opprobrium. Harassment over dowry – money and other goods demanded by the groom’s family – a practice that is officially illegal but still continues, can lead to deaths and suicides.

The weddings of the wealthy, the trappings of social tradition and the entrenched practice of dowry put immense pressure on lower-middle-class and poor families. But some social initiatives are hoping to change that.

A culture of extravagance

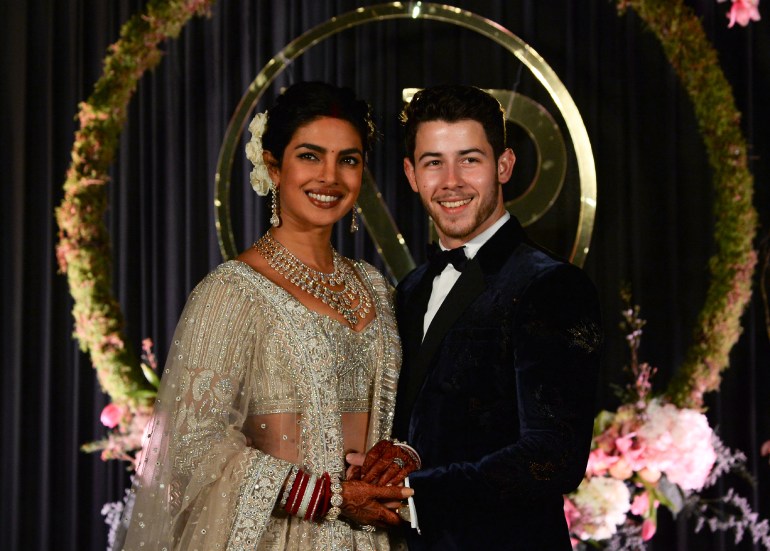

The high-profile nuptials of the rich and famous set impossibly high standards for the middle classes and the poor to emulate, triggering unnecessary social pressures, according to Dr Ranjana Kumari, director of the Center for Social Research, a New Delhi-based think-tank.

In 2018, the wedding of Isha Ambani, the daughter of Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man, cost a rumoured $100m. The multiple-destination celebration starring guests like Hillary Clinton and Beyonce dominated national news for days.

The five-day 2016 nuptials of the daughter of mining baron and politician Gali Janardhana Reddy at an estimated cost of $74m had gold-plated invitation cards, 50,000 guests and samba dancers flown in from Brazil. In 2004, for the $60m, week-long marriage of steel tycoon Lakshmi Mittal’s daughter Vanisha to London-based investment banker Amit Bhatia, about 1,000 guests, including Bollywood stars, were flown to France. The festivities included an Eiffel Tower fireworks display and a private show by Kylie Minogue.

Such extravagance, according to Kumari, seems especially misplaced in a country where millions of people go hungry. India ranks 94th out of the 107 assessed countries on the 2020 Global Hunger Index with a level of hunger that is categorised as “serious”. According to the Index, 14 percent of Indians are undernourished and 34.7 percent of children under the age of five are stunted.

High wedding expenditure also seems incongruous in a country ridden with glaring societal inequities. Today, the wealthiest 1 percent hold four times the wealth held by the poorest 70 percent of the population, or 953 million people, according to an Oxfam report.

In recent years, lawmakers have tried to curb excessive wedding spending and the pressure this places on underprivileged families.

In 2017, the Marriages (Compulsory Registration and Prevention of Wasteful Expenditure) Bill was introduced in parliament, proposing that families who spend more than 5 lakh (about US$7,000) on a wedding must donate 10 percent of the overall cost of the weddings to brides from poor families.

Bollywood’s influence

In an iniquitous social setting such as India’s, the role of Bollywood or the Hindi film industry in creating pressure to overspend on weddings cannot be ignored, say observers. “In Indian movies, wedding functions are highly glamourised events with fancy attires, and song and dance sequences in scenic locales. As cinema has a powerful hold over the mind of the masses, such depiction creates an aspiration among all classes of youth to mimic such splendour at their own weddings too,” says Kumari.

The proliferation of international global fashion chains in second and third-tier Indian cities is further creating newer avenues for consumption at weddings among all classes, say some.

“Everybody is into designer merchandise these days,” says Pratibha Chahal, a Mumbai-based sociologist. “Add to it the trend of hiring wedding planners, stylists, florists and multiple vendors for weddings and you have a toxic cocktail which has added so many unwanted layers to an Indian wedding today. All this expense pushes up cost dramatically.”

This level of consumption was not prevalent earlier, says Chalal, referring to the decades prior to the 1970s, which is when weddings started to evolve. Back then, weddings were largely family affairs and everyone pitched in to cook, decorate the house and handle all functions themselves, she says.

“Indian weddings are more about showing off one’s wealth and status and not really about the institution,” says Veena Trikha, 55, a schoolteacher whose son married last year. “It puts middle-class families under tremendous social pressure to spend more, perpetuating a culture of overconsumption. The perception of what society thinks about us always drives our thinking.”

An obsession with gold ornaments, also considered auspicious, is another factor contributing to overspending. “Indians are known to mortgage properties, take as many personal loans as they can afford or beg and borrow just to ensure that there’s enough display of gold at a wedding. In certain regions, people explicitly demand gold as dowry in the name of ancestral tradition. Even the poorest of parents will try to give at least one gold chain to their daughter to save face,” adds Kumari.

Unsurprisingly, India is the world’s second-largest consumer of gold, buying nearly 700 tonnes in 2019. More than half of this demand can be attributed to bridal jewellery, according to Chahal.

‘Girls are reduced to all about being married off’

Beyond the influence of unrealistic weddings, one of the grimmest aspects of a culture of overconsumption is the social malaise of the dowry. Dowries can include cash, real estate, cars, jewellery and other material items.

Middle-class and poor families often start planning for their daughter’s marriage from the time she is born.

According to Sunita, whose family faced crippling dowry demands, girls are considered a “curse” for poor families because parents see them as a burden due to the wedding expenses involved in their marriage. “Girls are reduced to all about being married off,” she says. “Her education, her career, her happiness – everything takes a back seat in front of her marriage.”

“Marrying off a daughter is an onerous responsibility in our section of society; there’s nothing joyous about it,” says Rani Devi, 56, a small-hold farmer from Hardoi district of the northern state of Uttar Pradesh whose daughter Shanti, 21, was recently married to a man from a neighbouring village.

Devi says that as her son-in-law had a bachelor’s degree, his family demanded a motorcycle and a gold chain for the groom for which she had to borrow about $1,000 from her relatives.

“As a widow, I requested the boy’s family to settle for a simple ceremony at a local temple, but he refused. His family said it was a matter of social status for them that their only son have an elaborate wedding. We had to pay for all the groom’s wedding arrangements too,” she says.

As girls are often seen as a financial liability, wedding expenses related to their nuptials could also be one of the reasons for the country’s skewed sex ratio, say experts.

India’s current gender ratio (112 males/100 females) is driven by a parental preference for sons that leads to sex-selective abortion practices and gender imbalances, according to Delhi-based obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Samriddhi Kakkar.

“The son is seen as an investment in the future; as someone who will take care of old parents, unlike daughters who marry and leave the home. So a premium is placed on the son’s birth. As dowry is invariably involved in a daughter’s wedding, she is seen as a liability,” says Kakkar.

“In India, men have a rate card,” explains New Delhi-based civil rights layer Shashikala Kandhari.

“Those with better education or secure government jobs have greater brand value in the matrimonial market. And that worth is assessed by the amount of dowry – in cash or kind – they will get upon marriage from the bride’s family. In India’s patriarchal society, men have always been valued over women and the practice of dowry is an offshoot of that retrogressive mindset,” says Kandhari.

Dowry exploitation

Despite economic progress, this heinous custom of dowry still flourishes in India across all levels of society, making women vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

According to Kandhari, the practice exists despite comprehensive legal provisions. Under the Dowry Prohibition Act of 1961, both giving and accepting dowry in India is an offence and the punishment for violating it is at least five years of imprisonment, and a fine of either $200 or the value of the dowry given, whichever is higher.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, every hour an Indian woman is driven to suicide or is murdered over dowry. Every four minutes, a woman faces cruelty from her in-laws or husband. In December last year, a 27-year-old woman set her house on fire and then jumped into the blaze with her two sons in a village in the state of Rajasthan. She was allegedly harassed for dowry by her husband and his family.

In another case reported in Bengaluru in early 2020, a husband demanded cash a few weeks after marriage despite receiving a kilogramme of gold in dowry as per his demands. When his wife refused, he burned her alive.

“In 1983, Sections 304B and 498A of the Indian Penal Code were also enacted to prohibit cruelty by husband or his relatives towards a woman,” says Kandhari, the lawyer. These sections are intended to help women seek redressal for cruelty and harassment. In the case of a woman’s death, prison sentences can be extended for life.

However, due to poor implementation of the law, most dowry cases take years to be resolved. Backlogs in courts and a lack of solid evidence to prove that dowry was demanded means the perpetrators are rarely convicted, according to Kandhari. Between 2006 and 2016, only one of every seven cases ended in a conviction, with five resulting in an acquittal and one being withdrawn, according to the National Crime Records Bureau.

Debt bondage

According to research by Pragati Gramodyog Evam Samaj Kalyan Sansthan (PGS), a pan-India non-profit that focuses on the intergenerational slavery of marginalised communities, more than 60 percent of Indian families turn to money lenders to borrow funds for wedding ceremonies.

“We have come across hundreds of cases in our fieldwork where marriage expenses have pushed poor families to slavery,” says Subedar Singh, media coordinator at PGS. “Loans to cover wedding costs come with impossibly high interest rates, causing many families to fall into bondage to pay off the debt. Indebtedness in rural India is very high due to high expenditure on two social occasions – wedding and death ceremonies. The culture (of expensive ceremonies) is so entrenched in rural communities that it makes thousands of poor fall into debt bondage.”

PGS cofounder Jyoti Singh, whose late husband Sunit Singh launched the organisation in 1986, says that with social pressures at work, even the poorest families have to stretch themselves financially to organise weddings that are beyond their means.

“If they don’t, fingers are pointed at them. Some are even ostracised or their daughters tortured till the parents capitulate to the groom’s demands. In some Indian villages, the groom’s family typically asks the bride’s family to cover the entire cost of the wedding in addition to giving cash or other gifts. Lack of education, poverty, and patriarchy exacerbate these pressures,” adds the activist.

Singh adds that as many poor Indians do not have bank accounts, or often do not use them, they invariably turn to upper-caste moneylenders when they require large sums of money for their weddings. “They are rarely able to repay these debts because moneylenders impose annual interest rates of over 100 percent. As a result, poor families are often forced to become bonded labourers, slaving up to 18 hours in brick kilns, rice mills, construction sites, mines or steel factories,” she adds.

Law enforcement is virtually non-existent due to a thriving landowner-police-politician nexus, according to Subedar Singh, which precludes investigations into debt bondage. “When cases actually make their way to court, a judiciary overburdened with a backlog of cases and the ignorance of the poor about the intricacies of law leads to traffickers’ acquittals,” he says.

Winds of change

Notwithstanding the culture of extravagance and the social malaises linked with Indian weddings, change is under way. Civil society organisations and individuals are stepping in to strike at the roots of customs that push families into elaborate weddings.

To combat debt bondage, PGS for the past seven years has organised group weddings for couples whose families are at risk of slavery. The ceremonies are kept simple and guests limited to 50 from each side to prevent the families from accruing crippling debt. “Instead of about $1,000 – the amount a typical wedding in these areas (rural northern India) usually costs – each family only pays only $15 for the ceremony so that they don’t fall into debt. Our network of donors pitch in to help as well,” explains Jyoti Singh.

These events encourage the families to invest any money they have saved in small businesses, buying cattle or sending their children to school, adds the activist, and show others an alternative way for weddings to be done.

Kiku Ram and Rani Kumar, both 26 and farmers in Noida, Uttar Pradesh were married at one such event last year. “I’d never imagined that my wedding would be a happy occasion incurring no financial burden on my parents. Throughout my childhood I was witness to my parents worrying about my marriage expenses. But my community wedding solved all their problems,” says Rani. “I wish every girl in society could marry like this.”

According to Suresh Kumar Goyal, coordinator for Narayan Seva Sansthan, a non-profit that organises mass weddings across India for underprivileged and physically disabled people, such weddings send out the right social message – that marriages ought to be joyous occasions and free of any kind of burden.

Launched in 1985, the non-profit organises two community weddings every year for 51 couples in different parts of the country. “All expenses for the nuptial ceremonies are borne by our organisation and our donors. All these families belong to the lowest rung of society and are financially incapable of formalising their own weddings,” says Goyal.

Kanyadaan India Foundation, another pan-India non-profit, was similarly set up to help poor families marry their daughters off in a dignified way. “We try to support the girl and her family by bearing all expenses of the wedding so that dowry and suicide due to lack of funds for marriages do not happen,” says the organisation’s spokesperson.

#Notobigfatwedding

Individual efforts are also targeting patriarchal and established wedding conventions. Hammad Rahman, CEO of Muslim matrimonial website Nikah Forever, has launched the #Notobigfatwedding campaign to popularise sustainable and minimalist weddings, cautioning people to not overspend.

The campaign has garnered more than a million signatures from the public over the past year. Rahman’s message is particularly pertinent as the coronavirus has forced people across different segments of society to opt for simpler weddings.

“We aim to promote this idea among youngsters. This is the ideal time to make people realise that we should reject useless traditions that encourage pompous weddings. It’s great to see people adjusting their wedding expenditure even if it is due to the COVID-19 threat. Our campaign aims to remind the world that weddings are the union of two souls rather than a trade-off between wealth and status,” elaborates Rahman.

Smita Gupta, a wedding planner, has seen people shying away from excessive spending due to the pandemic and believes this pattern could be here to stay. “It is clear that the industry will look very different post-pandemic.”

As the wider wedding culture faces a shift, experts feel that, apart from private initiatives, the government too needs to step in to organise mass sensitisation campaigns that educate the public about the ills of dowry, debt bondage related to marriages and the need to have simple weddings.

Better education can empower women to stand up and challenge illegal practices like dowry while helping men fight the pressures dictating that they conform to such social norms, says Kumari.

“Increasing government transparency regarding the investigation and prosecution of exploitative moneylenders and establishment of fast-track courts that address debt bondage are also critical to strike at the roots of irrelevant social customs that cripple the poor,” says Kandhari.