Inside Baltimore’s human trafficking industry

Survivors of sex trafficking and those who investigate it in the city share their stories.

Baltimore, Maryland – Taylor* was 13 when she first became a victim of sex trafficking. She had recently escaped from an abusive home and was living on the streets of Baltimore.

She was too young to work legally, but a close friend told her that she could make money by giving massages. Anxious to make a living, Taylor agreed.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWill Israel’s war on Gaza sway South Africa’s election?

Masked Tunisian police arrest prominent lawyer for media comments

Gaza’s mass graves: Is the truth being uncovered?

“When I got out [to the hotel where the job was supposed to be] it wasn’t what I expected,” she said. “I got there, and they wouldn’t let me leave.”

It turned out that her friend was recruiting girls for a human trafficker. The traffickers forced Taylor to live and work out of hotels for the next two years.

A hotspot for human trafficking

Baltimore, Maryland is a hotspot for human trafficking, according to experts. The confluence of highways, including the I-95 corridor that connects Baltimore to other nearby cities like Washington, DC and New York City, combined with the proximity to several major airports, a plethora of hotels and casinos, and extreme poverty beside extreme wealth, has created the perfect conditions for the trafficking industry to thrive.

Several interstate highways cut through the heart of the city, running on the east and west of the Baltimore port. Thousands of trucks, cruise lines, and cargo ships pass through Baltimore each year.

Meanwhile, deep social divisions and a long history of racial and economic inequality also mark the local landscape. More than 100 years of segregation and racist housing and economic policies have divided Baltimore into an L-shaped corridor that runs north to south, where an advantaged majority white population lives, and a butterfly-shaped majority Black area spreading through the east and west of the city.

The “white L”, as it is known, enjoys access to public transportation, bike lanes, and quality grocery stores. The majority Black neighbourhoods, meanwhile, are plagued by urban blight; dotted with boarded-up abandoned houses. These neighbourhoods experience gun violence paired with police brutality, including the now infamous 2015 murder of a 25-year-old Black man named Freddie Gray.

Today, neighbourhoods that are less than 50 percent Black receive almost four times the amount of investment as those where more than 85 percent of the population is Black, according to the Washington DC-based think-tank the Urban Institute.

These differences play out even in life expectancy, with a 20-year gap between the city’s wealthiest neighbourhoods and its poorest. And inequality extends past the city’s borders and into the suburban sprawl.

At more than 20 percent, Baltimore city’s poverty rate is around double the national average. Maryland itself, in contrast, consistently ranks as one of the wealthiest states in the country in regards to average income and economic opportunity. Some of the country’s wealthiest people live in a state whose largest city is plagued by poverty.

What this means is that those who can afford to pay for sex live within close proximity to those most likely to be targeted by traffickers.

As a result of this and its proximity to other large East Coast cities, Baltimore has one of the highest rates of human trafficking cases in the country. Washington, DC – just 64km (40 miles) away – is believed to have the highest rate.

According to local law enforcement, people engaged in commercial sex work in Baltimore often make more money than those in other cities, and that fact is what motivates traffickers from other parts of the country to flock to Maryland.

Poverty

In Pennsylvania Station, Baltimore’s main train station, flashing billboards tell onlookers how to spot the signs of human trafficking – unrelated girls with matching tattoos, for example – and which numbers to call if they see something suspicious.

Awareness among the general population is growing, but the problem is intractable.

“I think the I-95 highway plays a huge role in it. We also have an airport with really inexpensive flights. We’re a hub for those airlines, and that certainly contributes to it,” said Amanda Rodriguez, the executive director of Turnaround Inc, a Baltimore-based organisation that provides services to victims of human trafficking.

Rodriguez is a lawyer who spent years prosecuting human trafficking cases in the Baltimore area before she began working for Turnaround.

“I think trafficking is also related to socioeconomics in Maryland,” she said. “We have a lot of poverty, and it’s right next door to a lot of wealth, so you end up with people who can buy sex and people who are desperate. Poverty, in general, is a vulnerability that we need to address if we’re going to address trafficking.”

‘They approach you like mother figures’

Jennifer*, a soft-spoken woman in her late 40s with flecks of grey in her hair, described her childhood in Baltimore as “destructive.” Her cousin and his friends sexually abused her repeatedly from the age of seven to 13.

“My mother just wasn’t around, and my grandparents weren’t watching,” she said.

Later in life, Jennifer worked a steady job for years before an abusive relationship, and chronic stress drove her to alcoholism. She fell into depression and lost her job.

“I lost my house, my car, my dog, my kid,” she explained. “I lost it all, and I was on the streets for a while. I lost a sense of purpose.”

Jennifer began spending time in nightclubs, and she was often in need of a place to sleep. That was when traffickers began offering assistance. Sometimes, it was men who approached her, but on other occasions, it was women.

“You have the women that have been groomed. They’ve been through it and now, they’ve graduated a little bit, and now, they’re working to get you to do things so that they don’t have to,” she said.

“They approach you like mother figures. They approach you in the nicest way. [But] … you have to know that it’s not for free.”

Opioid epidemic

Homelessness and housing insecurity can put people at risk of being trafficked. On any given night in Baltimore, there are estimated to be around 6,500 people experiencing homelessness, or roughly 1 percent of the city’s population.

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, a non-profit, estimates that one in six of all missing children is a victim of human trafficking.

Many of the victims have complex histories of sexual abuse, trauma, and addiction, experts said.

In a country that has endured an opioid epidemic since the 1990s, Baltimore still stands out. More than a thousand people in the city die each year from overdoses. Heroin, in particular, has devastated the city since as early as the 1960s, and Baltimore was once dubbed the heroin capital of the United States.

Now, much of that heroin has been replaced by the cheaper and even more deadly fentanyl, but the high rates of addiction and overdoses continue. Baltimore, today, has one of the highest overdose fatality rates in the country.

Addiction, coupled with the high rate of poverty in the city, creates ample opportunity for children to be neglected or abused, experts said. This, in turn, puts those children at risk of being trafficked.

“Those who have histories of abuse or neglect or are runaways are especially vulnerable, as are people who have experienced some sort of trauma,” explained Janniece Phillips, a programme manager with the Araminta Freedom Initiative, another organisation that provides services to survivors of human trafficking in Maryland.

Araminta is currently working with 18 survivors and their children in Baltimore. Most of the survivors are 15 or 16 years old.

Hidden trafficking

Special Agent Kelly Baird, who leads a team with Homeland Security that investigates human trafficking in Baltimore, said that sometimes traffickers pick victims up directly off the streets.

“I had a case in which two men had a longstanding relationship. They weren’t related, but they still considered themselves father and son, and they were very active in recruiting women and children right off of the street,” Baird explained.

“One victim had been a chronic runaway. They rolled up next to her in their Chevy and started talking and, knowing that she had nowhere to go, she got in the car with them.”

For several months, the victim was expected to engage in commercial sex acts in exchange for food and a place to stay. She was 15 years old.

She was made to visit customers across the city, and was frequently put in danger. One customer cut her hand so badly that she had to seek medical attention.

Eventually, the sheriff’s department in a nearby county learned about the two men while investigating a separate case. The department contacted Homeland Security, which eventually located several of the men’s victims, including one who was addicted to heroin.

Following an investigation, one of the men was indicted and entered into a plea agreement. The other was murdered before charges were brought against him.

Local law enforcement works hand in glove with Homeland Security to tackle these cases, the special agents said. Patrol officers are the eyes and ears on the ground.

Investigators, meanwhile, rely heavily on data mining and search warrants to investigate cases, essentially trawling the internet to figure out where traffickers advertise to potential customers. In previous years, a website called Backpage.com advertised prostitution, but the site was taken down in 2018.

Some officials have argued that Backpage was useful because it allowed law enforcement to easily obtain the phone numbers, email addresses, and other details about the traffickers paying for ads.

Once the agents locate a victim, they can use conventional investigative techniques, such as interviews, to discover more details about the traffickers. But the internet is often where they find the victim in the first place.

Trafficking has become more opaque since Backpage.com was taken offline, investigators said. Instead of one website, now, there are many.

A destination and a source

John Eisert, special agent in charge for Homeland Security investigations in Baltimore, said that the opioid epidemic and other drug problems plaguing the city contributed to the prevalence of human trafficking.

“We have major trucking lanes and a major port. There’s a convention centre, sporting events; there’s a booming tourist industry with hospitality, so hotels and motels. It creates a certain problem set,” said Eisert.

“But there’s also the opioid epidemic that’s coming across the state of Maryland. It is very prevalent here.”

According to the Polaris Project, which operates the US National Human Trafficking Hotline, traffickers often use addiction to manipulate their victims.

Human trafficking is one of the top priorities for human services investigations across the country, Eisert said. But Baltimore has its work cut out for it. Some cities are destinations for human traffickers, and some are sources of trafficking victims, but Baltimore is both.

“We’re a hub city, while other cities are just a transit city. There’s turnover in the victims we see and the targets we see, but it’s a constant, unfortunately,” he explained.

A happy childhood

Despite the city’s problems, Taylor remembers her childhood in Baltimore fondly. From early childhood until about the time she turned 10, living in Baltimore was amazing, she said.

“We had block parties, I was in a marching band, I went to camp,” she remembered. “It was fun growing up, but then things started to change.”

Taylor’s parents were separated and both living in poverty, but things did not really start to fall apart until there was a series of incidents of sexual abuse in her family.

Everything in Taylor’s life began to shift as she hit puberty. Suddenly, it became harder to ignore the crime that plagued her neighbourhood.

Taylor witnessed one of her cousins being raped. Her brother was molested and raped by her cousin’s boyfriend who lived across the street, and Taylor, too, was molested by a cousin.

As Taylor described her experience, the words poured out of her as though she was just beginning to understand the emotional complexity of her story. She cried as she described how her childhood experiences led to her being trafficked.

Taylor felt like she could not talk openly to anyone about her experience of sexual abuse because her brother had already gone through something similar.

“I thought people would think that I was only saying it because he said it,” she admitted.

Taylor started to rebel and began to clash with her mother.

“My mother thought that beating people was OK. She wanted us to suck it up,” she said. “My siblings could, but I couldn’t. I wasn’t OK with my mom beating me with an extension cord or a shoe or whatever.”

Sometimes, Taylor’s mother would kick her out of the house. On other occasions, Taylor ran away from home.

In the shadows

While the majority of prosecuted trafficking cases in Maryland are sex trafficking cases, labour trafficking is also taking place in the shadows.

Experts said that labour trafficking can be harder to detect because the victims are often immigrants who are reluctant to report the abuse.

“The majority of the cases are sex trafficking because it’s far more prevalent and easier to detect,” Baird explained. “Labour trafficking is in the dark, it’s in the quiet, and to a certain extent, people are more reticent to report, as well.”

In one recent case, for example, a woman from Zimbabwe was held in slavery for around eight years. She had been recruited to work as a domestic servant and was promised money and an education, but none of those promises materialised.

“She was exploited the whole time she was here,” Baird said. “She also didn’t want to disappoint her family at home, so she had all of these financial and social pressures that account for why she stayed in the situation.”

After four years working in captivity, the traffickers started letting her attend church services. When, years later, she eventually described her living situation to her pastor, he told her to put her belongings in a bag, go outside, and he would rescue her.

“The difficulties with labour trafficking are that it’s very insular. Neighbours knew her. The traffickers gave her permission to attend church services, so the parishioners knew her, but she was given rules. She had to tell people that she was a family friend, she couldn’t tell them that she was working,” Baird explained.

For years, the victim did as she was told.

“The traffickers would threaten her by withholding her passport and threatening to send her home,” Baird said.

Today, she has a visa that allows her to remain in the US, and she can access services like subsidised housing. She started attending school to become a nurse.

Safe harbour laws

The state’s human trafficking laws recognise that immigration status can be used to extort victims, and it allows officials to prosecute any case in which a victim is “persuaded, induced, or enticed” into trafficking. Still, Maryland has not yet passed a safe harbour law that prohibits the criminalisation of minors for prostitution.

Thirty-four states, including Kentucky, Mississippi, Nebraska, North Dakota and Tennessee, have passed safe harbour laws.

According to Turnaround’s Rodriguez, politically conservative states sometimes have an easier time passing safe harbour laws because legislators tend to view human trafficking as a humanitarian issue. Since Maryland is a majority Democratic state with a large Republican population, policy issues can get bogged down in discussions about the approach.

“If you had asked me even five years ago, I would have said that Maryland is doing really well, especially policy-wise,” Rodriguez said. “Maryland was number two in the nation introducing vacatur laws related to trafficking. But we’re seeing other states moving forward, and Maryland doesn’t seem to be doing that.”

“Maryland is a deeply purple state, so because those two ideas work against each other, it can be hard to get the ball moving. We’re often really late in terms of introducing things,” she continued. “There have been a lot of conservative states that have introduced safe harbour and gotten it passed.”

Law enforcement and others in the city are learning, however, that trafficked women and children are victims and survivors, not criminals.

Maryland’s laws were amended as recently as 2015 to allow a person charged with prostitution to defend him or herself by arguing that they are a victim of human trafficking operating under duress.

Over the past several years, Baltimore City’s Human Trafficking Collaborative has brought together law enforcement, prosecutors, non-profits, healthcare providers, and state and city agencies to combat trafficking and support victims. Places like Turnaround Inc and Araminta are all part of that collaboration.

Changing perspectives and increasing awareness

Thomas Stack, the Human Trafficking Coordinator for the Baltimore Mayor’s office, said his view of the issue had radically changed since he first began investigating human trafficking cases and shutting down Korean-run massage parlours over a decade ago.

“I started to change the way I looked at things and went 180 degrees,” Stack said. “I went from ‘nail them and jail them’ to seeing the girls in prostitution as victims.”

When Stack started working in the police vice unit in 2000, human trafficking was not a commonly used term, he recalled. But over the years, as he encountered more victims, his outlook began to evolve. Stack gained a greater understanding of the relationship between poverty, the abuse of runaway children, and prostitution, and discovered that shutting down massage parlours and arresting people was not going to address the issue at its root.

Today, the city’s law enforcement and the members of the Human Trafficking Collaborative take an approach that puts the victims first. Each hospital in the city has a representative tasked with understanding how to identify victims of trafficking if they seek medical attention. Members of law enforcement visit local schools in at-risk areas and talk to the students.

In March 2019, Baltimore launched a secret programme that allows law enforcement to call a local hospital at a moment’s notice to ask for services for trafficking victims. An official just has to use a specific code word and the healthcare providers automatically know that a human trafficking victim will soon arrive. A forensic nurse, a victim’s advocate, and security guards are made available immediately. It is a coordinated effort that ensures trafficking victims get immediate support that is free and anonymous. The victim’s phones are put on airplane mode and security guards with canines make sure the trafficker cannot hunt the victim down.

“The awareness is definitely increasing, especially with the first responders coming into contact with the victims,” said Phillips from Araminta. “Instead of victims being punished for being victims, the response is to ask what their needs are and what we can do to help them recover.”

An uneasy neighbourhood

The Curtis Bay neighbourhood in southern Baltimore is one of the areas of the city that advocates for trafficking victims often point to as a place of extreme vulnerability. More than 39 percent of families there live in poverty, according to recent government statistics.

The neighbourhood is also a place where long-distance truck drivers pass through the city to make deliveries near the port. There are casinos and strip clubs nearby, and the neighbourhood’s Fairhaven Avenue is known for prostitution.

At first glance, Curtis Bay looks like any run-down post-industrial neighbourhood from which businesses have slowly vanished. The grey streets are dotted with small homes that were built to provide cheap housing during the post-World War II population boom. There are a few dingy bars, numerous tobacco shops, and convenience stores selling Baltimore’s signature snowballs – a cup of fluffy, shaved ice drenched in sweet, artificially flavoured syrup. During the day, the streets are quiet. The port and trucking lanes loom to the east.

But there is an overwhelming feeling of unease in the neighbourhood. Residents warn against visiting the local gas station, noting that there are frequent gunfights between rival gangs. The local shops discreetly sell scales for measuring heroin or other drugs. The unemployment rate is usually around 11.8 percent compared to 7 percent across Baltimore and 4.5 percent in Maryland as a whole. Residents look at outsiders with suspicion, assuming that they are in search of drugs or prostitutes.

The vice unit for Baltimore City Police has been working in the area to curb the demand for commercial sex, according to people familiar with the matter. Women living in the area, however, said that potential customers still pass through the neighbourhood regularly.

Meredith*, a trafficking survivor who lives in the area, said that men often approach her for sex when she walks down the street in Curtis Bay, but now, she has learned to fend off their advances.

She said the neighbourhood has a drug and alcohol epidemic. Around 9 percent of all deaths in the area are caused by drugs or alcohol, according to government statistics.

“There’s drug dealing and drug addicts, and there’s a lot of violence, people shooting everybody,” she said. “And there’s prostitution along with the drug addiction.”

Welcome at the Well

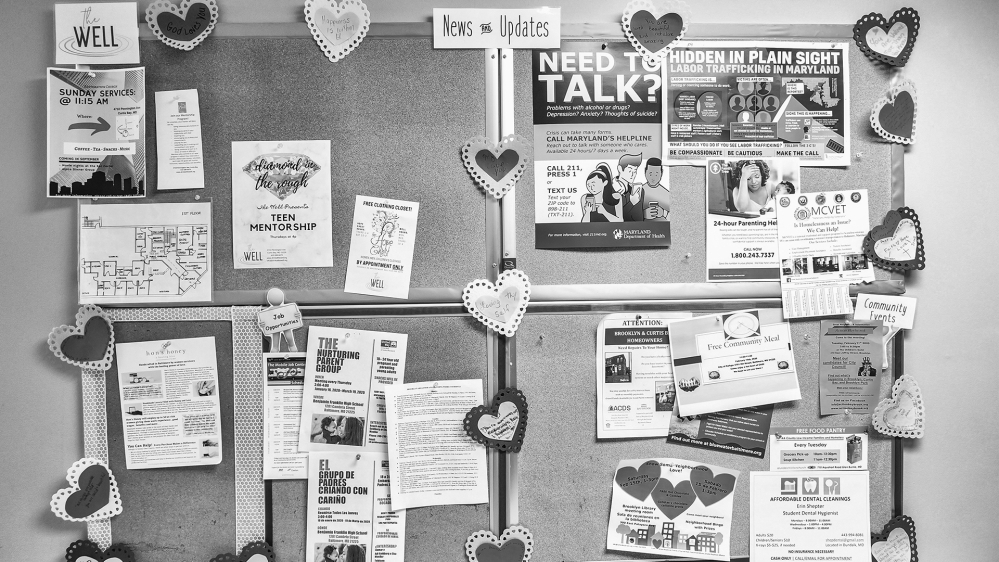

On a corner of the main thoroughfare of Curtis Bay, a long street lined with run-down convenience stores, is the Well, a community centre located on the bottom floor of a plain red brick office building where women can come together to heal. The centre shares the unassuming building with a cardiologist, a clinical therapist, and a church.

The Well, which opened in 2015, is the brainchild of Mandy Memmel, a Baltimore resident with sparkling blue eyes, a gentle but firm demeanour, and a background in church ministry.

The centre opens its doors to women who have experienced sexual exploitation, abuse, and addiction. It also offers a long-term mentorship programme to women who are looking to rebuild their lives, and every year it offers hundreds of mentorship sessions on everything from housing to how to obtain an ID or birth certificate and dealing with trauma. Around 35 women went through the organisation’s mentorship programme in 2019.

The Well also has a social enterprise on site, called Hon’s Honey, where the women make soap and other bath and beauty products from honey, essential oils, and other natural products. Hon’s Honey’s office space is filled with women and the pungent smell of flowery soap and essential oils.

The proceeds from the products are used to offer survivors part-time employment. For many of the women, it is the first job they have ever had.

On the wall of the Well is a sign that reads “We loved you from the moment we saw you”. The organisation’s philosophy combines radical acceptance with a belief that love and meaningful, supportive relationships can help people heal from childhood trauma and sexual exploitation, including human trafficking.

Women from the neighbourhood arrive in the office each day with their children. “Am I still welcome here even though I haven’t been here in a while?” asked a woman walking into the front office with her daughter in the middle of the afternoon. The woman was middle-aged, but she spoke with the timidity of a child.

“You bet you are,” responded the woman at the front desk.

Volunteers from the Well often walk around the Curtis Bay neighbourhood offering care packages with toiletries, clothes or sandwiches for the women and girls working on the streets. Those they encounter are aged anywhere between 15 and 60 years old, the volunteers said. They let them know that they can always come to the centre for a shower, food, or just a rest.

‘Unconditional love’

Women like Jennifer, who was raised in Curtis Bay, have found refuge at the Well.

Jennifer now helps other vulnerable women and trafficking victims.

“I walk through the streets, and I go up to them, and I ask how they are. If you walk up and down Fairhaven [Avenue,] you will see them. We go and hug them and talk to them. We find out what’s going on and if there’s anything they need,” she said. “Healing with them helped me overcome what happened to me.”

Jessica*, 49, another survivor who spends time at the Well, said her mother’s boyfriend raped her when she was just three years old. Later, she experienced behavioural issues and was plagued by nightmares. As a very young adult, she developed a cocaine addiction.

“Everything that I hated and everything I despised is who I became,” she said, describing that period of her life. “I had no emotion. I was mechanical. I was a soulless shell.”

Today, Jessica said that the friendships she has built at the Well have been transformational.

“I need the Well for emotional stability. I always have someone there to lean on,” she reflected. “The genuine and unconditional love that I’ve found here is something that everyone needs, but a lot of people will never find.”

*All names of survivors of human trafficking have been changed to protect their privacy.