Why Trump’s America is more divided than ever

The sorting of Republicans and Democrats along racial, ethnic and religious lines fuels toxic partisanship in the US.

![People and Power - US [DON''T USE]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/2e3904c272244c69b53f8b852644108c_18.jpeg?resize=730%2C410&quality=80)

Hyper-partisan politics in the United States were on display in July when former Special Counsel Robert Mueller appeared before the House Judiciary and Intelligence Committees to answer questions about his investigation of President Donald Trump and Russian interference in the 2016 presidential campaign.

Democrats questioned Mueller, the former FBI director, about detailed evidence presented in his final report that Trump attempted to obstruct the investigation. Adam Schiff, the House Intelligence Committee chairman, underscored that “knowingly accepting assistance from a foreign government” is disloyal and unethical, if not a crime.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsTrump will not testify in New York hush-money trial as defence rests

Cohen admits to stealing and other takeaways from day 19 of Trump’s trial

Cohen faces more cross-examination as Trump’s trial enters final stretch

But at the hearings, Republicans repeatedly claimed that the Mueller report exonerated the president and that the origins of the FBI’s counterintelligence investigation of the Trump campaign in 2016 were corrupt. They assailed the value of the Mueller investigation, the money spent on it, and the motives of the people conducting it.

For many Democrats, there are strong grounds for impeaching Trump. But with Republicans remaining firmly in his corner, the sharp differences over impeachment are becoming symbolic of the deep partisan divide in the US.

John Dean, the former White House counsel whose 1973 testimony helped seal the fate of President Richard Nixon during the Watergate cover-up, believes that “history is repeating itself, the Trump administration is in fast competition with what happened in the Nixon administration.”

When Dean appeared before Congress in June, he warned that “there’s too much polarisation, you sense it in the questioning here and in the shots that get taken at witnesses.”

Traditionalist vs progressive: Clash over values

Trump exacerbates political polarisation. But the toxic partisanship in the US today is a result of a social sorting process that has given rise to Democratic and Republican parties made up of distinctive racial, ethnic and religious groups.

Lee Drutman, a senior fellow in the political reform programme at the think-tank New America, argues that the US is “at the conclusion of basically a 60-year political journey and it’s a disaster because right now the parties have divided over fundamental visions of the national character.”

“The Republican party basically sees the true national identity of America as in the past, a time when America was a white, Christian nation. It’s a traditionalist vision. And then we have another party, Democratic party, that has a very different vision of America. It’s a more secular place, it’s more progressive, and it celebrates diversity.”

This clash over values has led to the sorting of the parties along geographic lines. In the 2016 election, Trump won decisively in the 2,300 counties that make up small-town and rural US. But in cities, Hillary Clinton beat Trump in a landslide.

The parties have divided over fundamental visions of the national character. The Republican party basically sees the true national identity of America as in the past, a time when America was a white, Christian nation. It's a traditionalist vision. And then we have another party, Democratic party, that has a very different vision of American. It's a more secular place, it's more progressive and celebrates diversity.

North Carolina, a microcosm of political division in the US, is a good place to go to learn about the social and economic causes of the urban-rural divide, and its relationship to partisanship and incivility in the US.

“In some areas of the state it’s very hard for a Democrat to get elected and now in the cities, it’s very hard for a Republican to get elected,” political author and reporter Rob Christensen points out. He covered politics in the state for 45 years at the Raleigh News and Observer.

“In the metropolitan areas is a group of people that tend to be highly educated, who are more moderate to liberal in their views. It’s white and black. The rural areas are becoming whiter and older and the metropolitan areas are becoming more diverse.”

287g and ‘Trump’s deportation force’

Eight percent of North Carolina’s population is foreign-born, 51 percent from Latin America.

Manolo Betancur, who owns a bakery in North Carolina’s largest city Charlotte, immigrated from Colombia 19 years ago.

Betancur got involved in mobilising the Latino vote for Democrats in the 2016 election. He says that since Trump was elected, things have changed a great deal for the Latino community in the city.

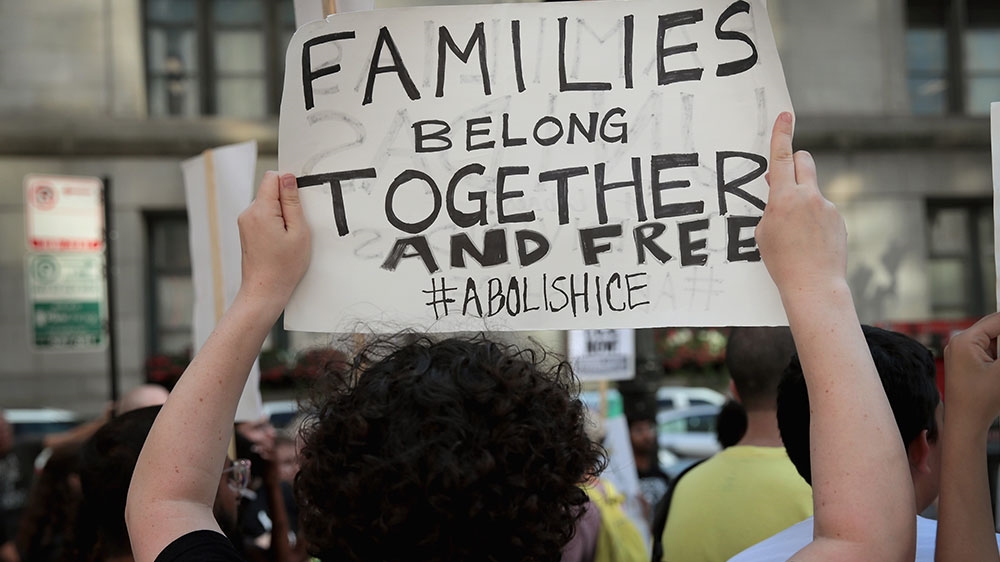

“They are destroying families, taking fathers and mothers away from their kids,” he says.

After Trump was elected, federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) became more aggressive in deporting irregular immigrants. In North Carolina, 59 percent of the Latino population is US-born. But there are about 100,000 undocumented immigrants in Charlotte.

At the time, the local sheriff in Charlotte was working with ICE under a programme called 287g, so Betancur and a group of local activists got involved in an effort to elect a new sheriff.

“287g basically expands the reach of ICE,” said Stefania Arteaga, an organiser with the Charlotte immigrant advocacy group Comunidad Colectiva. “It deputises local sheriff’s deputies to place foreign nationals into removal proceedings.”

In the run-up to the county sheriff election in May 2018, members of Comunidad Colectiva and other progressive groups hit the streets with a scorecard highlighting the differences between the incumbent Sheriff Irwin Carmichael and his challengers.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) also ran radio commercials advertising that Carmichael’s challengers “pledge to stop working with Trump’s deportation force.”

Garry McFadden, a homicide detective for 27 years, won, becoming the first African American sheriff ever in Mecklenburg County, which encompasses Charlotte. On his first day in office, he ended his department’s involvement in 287g.

“We already had communities with mistrust; no matter what happens in a community, the community says ‘you do not tell the police’, and 287g just compounds the problem because of fear that you will be deported or you’ll be targeted by ICE,” McFadden says.

McFadden says he also ended his department’s involvement in 287g because “a lot of people got caught up for small crimes. Driving with no license, seatbelt violations. As long as you got into the criminal justice system you were part of the deportation process.”

ICE responded to McFadden’s decision to end cooperation by mounting an aggressive enforcement effort in Charlotte, accusing him of being soft on crime.

Betancur says his bakery became a target for ICE action. People were stopped by ICE agents all around the bakery, discouraging people from coming to his establishment, he says.

Four vans came with people with weapons, with guns, and they just jumped out and grabbed one person, a regular person.

McFadden and other African American sheriffs in North Carolina’s largest urban counties, who won elections in 2018 because of their opposition to 287g, are now battling legislation pushed by Republicans that would force them to cooperate with ICE or be removed from office.

Like Republicans in Washington, DC, Republicans in North Carolina representing rural districts have been accused of fuelling partisan tensions by pushing policies on immigration and other issues opposed by urban residents.

Trump’s stance and rhetoric on immigration helped elect him and are among the issues that really divide Democrats and Republicans, Christensen notes.

“There is a very sharp difference about whether it’s good for the country to have a lot of people coming from Latin American countries or it is somehow eroding America’s authenticity,” he says. “Some of it’s just tribal, these are not people that look like me or the kind of people I grew up with. In some cases, it is economic competition or at least the view that there’s economic competition.”

Economic decline and the urban-rural divide

Christensen believes that economics is at the root of the urban-rural divide in North Carolina and the US as a whole.

“We have one half of the state that’s dynamic and it’s growing fast,” he says. “And the other half, you have a dying North Carolina. The rural areas are really struggling with economic decline. And so, of course, you’re going to have a huge urban-rural divide if that’s the case.”

An area of North Carolina that has struggled economically in recent decades is in the western part of the state, at the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. For most of the 20th century, you could find textile mills and furniture factories in the region’s small towns rivalling industry in the American Midwest. But that began to change in the 1980s.

|

|

The town of Valdese in Burke County had some 7,000 people working there daily in the early 1980s. Today it is closer to 2,000, according to Chuck Moseley, who works to bring new jobs and businesses to the town as the head of the Valdese Economic Development Corporation.

The first big economic hit Valdese took came around 1982 when the main plant of the Alba-Waldensian textile company shut down. At one time, the company ranked fifth in the world in the hosiery business, according to Moseley.

Valdese and the neighbouring town of Lenoir in Caldwell County also lost thousands of jobs in the furniture industry due to imports from Asia and the outsourcing of production to the region after China was admitted to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001.

“We were so focused on furniture and on textiles, people weren’t trained to do anything else,” Moseley says.

The 2008 recession also hit the area hard. Unemployment has come down since then but the problem, according to Moseley, is that too many of the new jobs that are available are “barely above the minimum wage.”

Moseley says that people in his community blame trade deals – the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and China’s admittance to the WTO – for their economic problems. And he says there is resentment that the establishment and politicians let ordinary people down.

“At the coffee shop, that was the talk,” Moseley says. That the politicians and company executives “are more interested in the dollar from Wall Street than they are the people that are making the furniture and the families they’re raising in this country.”

Drutman points out that, in the US, “political polarisation and inequality have run together for the last 40 years, as the country has grown more unequal, the parties have grown further apart.”

The two trends have gone together, Drutman says, because “as polarisation increases, so does political gridlock, and it becomes harder for the political system to respond to growing inequality. Inequality also creates more resentments which then get channelled into partisan polarisation.”

Political polarisation and inequality have run together for the last 40 years, as the country has grown more unequal, the parties have grown further apart.

In 2016, Trump targeted hard-hit small-town industrial areas in North Carolina, promising to stem the loss of jobs and bring them back. He received 67 percent of the vote in Burke County and 73 percent in Caldwell County, record levels of support for a Republican presidential candidate.

“When Donald Trump talks about American carnage as he did in his inaugural speech, he is talking about places like Caldwell County and Lenoir,” Christensen says.

“It resonates with those people because there’s been an emptying out of those manufacturing jobs. You’re seeing a decline in their whole civic culture that’s going on there. That’s why you have these really deep-seated problems like increases in suicide, and opioid use, and out of wedlock births. And it’s not just those areas but all rural North Carolina and a lot of rural America.”

Trump and the religious right

The appeal of right-wing populism in small-town and rural areas left behind by economic change plays a major role in America’s political divisions today.

But there is also a critical cultural dimension, according to Stephen Harris, a local newspaper columnist and resident of Elkin, a small town about an hour up the road from Valdese.

“In recent times we’ve had very stark choices between right and left and people here appreciate the traditional values that we see embodied in the right,” Harris says. “We don’t like some of the things that we hear from the big cities and we certainly appreciate and uphold the Bible and the morals that it teaches us. These things are still very important and we don’t want that to change.”

Harris says that evangelical Christianity is very strong in western North Carolina, along with support for Trump.

“President Trump supports or appears to support the traditional American values that are so important here,” Harris says. “We’re seeing things that our parents would never dream would happen in America such as abortion and same-sex marriage.”

White evangelical Christians represent 26 percent of the US electorate. They are Trump’s most loyal bloc of support, and he has advanced their agenda on relations with Israel, conservative judges, abortion, and LGBTQ rights.

Lilliana Mason, author of the recent book Uncivil Agreement, which examines the causes of polarisation in the US, says that “the divide between white Democrats and Republicans is really now between Christians and people who are not religious at all.”

Mason argues that the sorting of the parties along religious lines also fuels extreme partisanship in the US. “In the 80s and 90s we saw the religious right become involved in politics and they chose to unite with the Republican party which means that now we wrapped religion into partisanship as well,” she says. “And evangelical Christians hadn’t really been involved in politics before.”

Trump’s economic message also resonated in Elkin, which lost a textile mill that was the linchpin of the local economy.

Sara Carter, a friend of Harris’s who worked at the mill, says “they’re getting different things to come in, wineries and vineyards, and things are coming around now, that’s bringing some tourists in. But I don’t think it will ever completely recover.”

While rural America struggles, Trump has stoked partisan tensions with misleading claims about Democratic support for undocumented immigrants. At rallies, he has said that Democrats want to “sign them up for free healthcare, free welfare, free education, and for the right to vote.”

Louise Darnell, like other Elkin residents, agrees with the president on immigration policy. “They’re illegals, they should not take what is ours, what we have earned,” she says. “I think there should be very stringent laws and policies to keep them from taking our resources.”

Darnell also feels the divisions in the country will continue to escalate. “You have your economic classes, you have your races, you have your different religions and everybody believing my way is the only way.”

Evangelical Pastor Franklin Graham, whose Christian relief organisation Samaritan’s Purse is based in North Carolina, is also concerned about the divisions in America. “It is ripping some sections of our country almost apart and it shouldn’t be,” he says. “I don’t think we’re as divided as we were in the Civil War when the nation was ripped apart. And I hope that never happens again but it could, who knows.”

‘It’s time to fight for the heart and soul of this democracy’

Reverend Graham, the son of the Christian evangelist Billy Graham, participated in Trump’s inauguration and is a vocal critic of Democrats.

He believes that Trump won the presidency because of divine intervention and that only God can bridge the political divide in the US. “I think if all of us, Democrats and Republicans would turn our faces back to God and ask for his help I think we can come through these problems very easily,” he says.

The morality of a woman’s right to choose, or someone’s right to marry whom they want, didn’t seem to carry much weight with Graham. When asked if he was saying that the “only morality that matters is the morality of the Bible,” he said, “yes.”

But Reverend William Barber II, who launched the Moral Monday Movement in North Carolina, takes issue with Graham’s interpretation of the Bible. “The false moral narrative of religious nationalism and white evangelicalism seeks to make things ok as long as you’re against gay people, for praying in school, against women’s right to choose, for guns and for tax cuts,” he says.

Barber is now spearheading a new effort, The Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. “You got 62 million people working for less than $15 an hour and some have to get food stamps and live in cars because they don’t make a living wage,” he says.

“Our country cannot stand and continue to stand with that kind of gross inequality. So we’re saying it’s time for us to come together to fight for the heart and soul of this democracy.”

The extreme partisanship in the US has people in Charlotte worried that hosting the Republican Convention next year will be much different from when Democrats gathered here in 2012. “It’s going to bring something totally different. Totally different temperatures of America from 2012 to 2020,” Sheriff McFadden says.

Asked if he fears political divisions could lead to violence in the US, McFadden answers, “It will. I know it will.”

Christensen thinks that the US may have become so divided that it is no longer capable of safeguarding its democracy by impeaching a corrupt president as envisioned by the writers of the nation’s Constitution.

“I don’t think Richard Nixon would be impeached in today’s environment,” he says. “I think people would essentially rally around Nixon along partisan lines.”