Occupying Alcatraz: The spark that lit the US Red Power movement

Fifty years ago a group of activists set sail to reclaim Alcatraz Island, ushering in a new era of indigenous activism.

It was at one of the United States‘s most infamous prisons, more than a mile from any shore, that Eloy Martinez found a vision of freedom.

The adrenaline surging in his veins that night felt nearly unbearable. A cold wind whipped his face, and a coastguard blockade patrolled the waters nearby. Nobody knew whether the night would end in cheers or arrest.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsWhy are protests against France raging in New Caledonia?

‘No choice’: India’s Manipuris cannot go back a year after fleeing violence

Photos: Indigenous people in Brazil march to demand land recognition

But when dawn broke over the abandoned federal prison on Alcatraz Island 50 years ago, on November 20, 1969, a new era of indigenous activism was born. Alcatraz had been reclaimed as indigenous land. That statement would reverberate across the US, inspiring movements and changing federal policy for decades to come.

The protest’s architects were largely college students, united under the name Indians of All Tribes. For 19 months they held the island, sketching a blueprint for how the US could be.

They envisioned a centre for Native American studies, to combat colonialism’s corrosive effects on their culture. An ecology centre, to reverse the destruction of their land. And a museum, to honour indigenous contributions to the world.

“There was none of the naysayers around you. There were no rules. We could make our own rules. We had the run of the island,” Martinez says of that time.

|

|

A short man with a puckish grin and a grey, feathered fedora, Martinez still smirks at the irony: A cold, barren fortress, Alcatraz served as the perfect metaphor for the conditions on the reservations indigenous peoples had been forcibly moved onto.

“It’s unsustainable. No running water. Nothing grows to sustain you. Doesn’t have any animals on it. It was the same as a reservation,” he explains.

And yet, the original occupiers saw Alcatraz Island as a beacon of hope. They painted messages of freedom across its prison walls and erected a tipi on its shores – a West Coast answer to the Statue of Liberty. “She’s in the east, and we would be right here in the west, saying this is Indian land.”

At night, when the coastguard beamed floodlights across the island, Martinez remembers seeing sleeping bags stretched out in all directions: Tired masses, yearning as much as anyone to be free. Martinez himself had picked a plum cell at the bottom of the prison – comfortably close to the toilet, he chuckles – to curl up in at night.

Martinez, a member of the Southern Ute Tribe, was no stranger to injustice. And yet, camping inside the crumbling remains of a prison, he glimpsed a different kind of future: “I could see what sovereignty would be like.”

A first brush with discrimination

Sovereignty was never something he expected to find. He had seen coal companies tear through the reservation farmland his grandmother once called home, and his own freedom had been curtailed by stints in juvenile detention.

The trouble, he recalls, started when he was nine years old. He spent his summer working on his aunt and uncle’s farm in the Four Corners region of Colorado, and one day, he accompanied his cousins to haul milk at a local creamery.

The owner’s son had a reputation for groping the women while their hands were full, and Martinez called him out on it. His response was to push Martinez, taunt him, challenging him to knock down the stick he had slung over his shoulder to prove how tough he was. “I didn’t aim for the shoulder. I didn’t. I just hit him in the nose.”

That act of violence landed Martinez in court. The groping and the taunting made no difference. “The reaction we got from the judge was that I shouldn’t have hit him because he’s going to be my employer one day,” he says. “That’s the first time I really faced that discrimination.”

His worries did not stop at the summer’s end. Hoping it would give her son a better education, Martinez’s mother eventually enrolled him at a Catholic school, not knowing it was home to a priest who preyed on young boys.

“One of the kids committed suicide,” Martinez recalls, punctuating the thought with a loud, visceral “whew”, as if the shock had hit him anew. A talkative man, he now pauses. His eyes search the horizon. “I hadn’t thought about that for a long time.”

To retaliate, Martinez and other boys at the school punched out tyres and smashed windows – anything to drive the priest away. Their actions landed Martinez at a state industrial school in the city of Golden. There, every article of clothing he had, apart from his socks, was stamped with a number. “Fourteen eight fifty-four,” would be his name for four years, he says.

After his release, there would be more fights. More sheriffs knocking at his door. And after a while, Martinez had had enough. Newly married, he asked his wife Lesee to pack him a bag. He pointed his Volkswagen bus towards California and joined thousands of Indigenous individuals in migrating to the San Francisco Bay Area.

Termination through urbanisation

The economic boom following World War II made city life appealing, but not all newcomers arrived by choice. At the time, the US government was promoting a series of laws known as “termination” policies, designed to strip Native Americans of their sovereignty and force assimilation into mainstream culture.

Part of its strategy was to disband communities and to relocate them into urban settings. What emerged in San Francisco was a hotbed of young, Indigenous activism. Martinez’s wife soon joined him in the East Bay city of Oakland, and together they demonstrated alongside the United Farm Workers union and the anti-Vietnam war protesters of the late 1960s.

It was at one of those protests that Martinez met a pivotal figure in the Alcatraz movement: A tall Mohawk man he came to know as Richard Oakes. They forged a lifelong friendship over the bologna and cheese sandwiches Lesee had packed – an “Indian banquet,” Martinez quips.

Oakes ultimately helped concoct the plan to take over Alcatraz Island in a classroom at San Francisco State University. When Oakes dove into the waters off Alcatraz and reached the island on November 9, 1969 – as a kind of test run for the full-scale occupation – Martinez recognised it as a turning point. “That lit the spark of the Red Power movement. After that, there was no going back.”

Decades later, when Kent Blansett boarded a ferry to Alcatraz, he too felt an awakening. But he was equally struck by the chatter he heard around him from tourists eager to tour the prison cells of gangsters like Al Capone and Machine Gun Kelly. “I made the realisation they’re here for America’s toughest criminals. I’m on this journey for America’s toughest Indians (Native Americans).”

The lack of awareness came as little surprise. A history professor at the University of Nebraska, Omaha, Blansett regularly asks his classes if they know Oakes’s name. More often than not, the answer is no.

“Where would we be as a country if we didn’t know the name Martin Luther King? Where would we be as a country if we didn’t know the name Malcolm X?” he asks, ticking off prominent US civil rights leaders.

“We as native peoples weren’t the only ones colonised. Colonisation is a two-way street. For Americans to be truly awoken, they need to deal with their own colonisation. Why is it that they don’t know this history?”

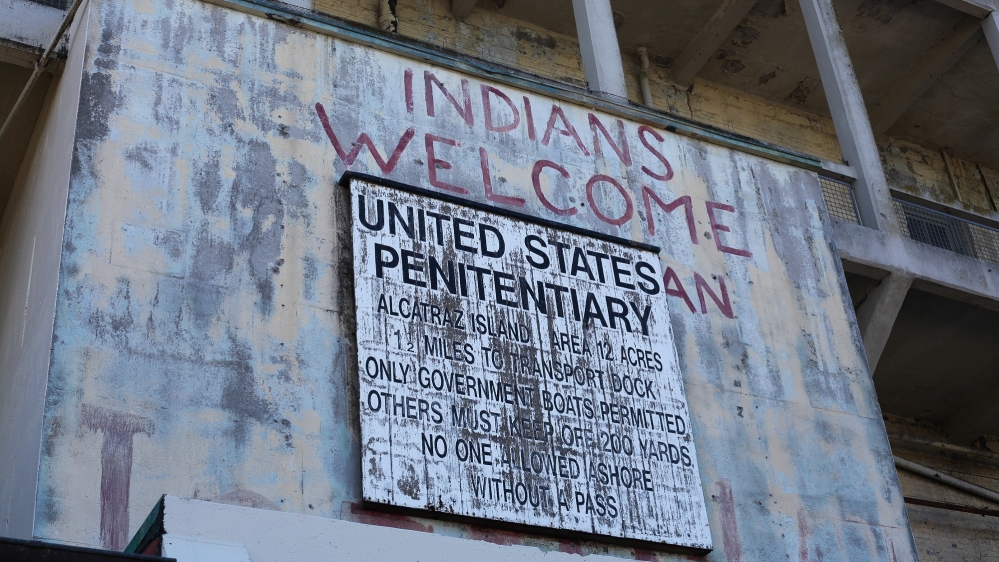

A welcome sign on stolen land

An indigenous man himself, descending from the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Shawnee and Potawatomi nations, Blansett only learned Oakes’s name as an underclassman at university. The discovery that his campus housed Indigenous remains – a desecration in the name of science – had launched him into activism, and he sought inspiration through research.

“My sanctuary at the university became the E stacks in the library,” he says. “That’s when I discovered Alcatraz.”

It was a stark contrast to the prevailing narratives he knew, which linked Indigenous activism to violence. “Most of the images, when you think about Red Power, revolve around the [1973] occupation of Wounded Knee. Essentially, Indians with guns,” Blansett says. “We became what America needed us to become. We became the villain in the story.”

But in Alcatraz, Blansett found an alternative. There was a non-violent movement led by both women and men, families in tow. Oakes, in particular, gave the young Blansett “new ideas of what Native masculinity is”.

“Native men were always seen in the stereotypical vein of not showing emotion, not being able to cry,” Blansett says. By contrast, with Oakes, “here’s this Native man who was powerful but who could also showcase emotion, showcase love.”

Blansett’s admiration for Oakes eventually led him to write the first book-length biography of the Alcatraz leader. But first, he felt he needed to visit the island himself – to stand at the tip of a boat and see what Richard Oakes saw.

As his ferry swung around to dock, goosebumps erupted on his skin. The message he saw before him, scrawled in red paint, shook him to his core: “Indians welcome.”

“As an Indigenous person, this was the first welcome sign I’d ever seen in my own homeland.” The sign filled him with pride – and the pain of wondering why he had not felt welcome in the first place.

Reclaiming a ‘sense of identity’

Alcatraz veteran Eloy Martinez still dreams of a day when he can walk down the street like any other person, a day when “nobody’s watching me like I’m an interloper”. He does not know if he will live to see it. He is 79 now and walks with a cane after a motorcycle accident broke his pelvis. He wonders aloud if this will be the last Alcatraz anniversary he and other original occupiers will share.

His friend, Richard Oakes, did not live to attend the reunions. On September 20, 1972, at age 30, Oakes was shot dead on a rural road north of Santa Rosa. His killer, 34-year-old Michael Morgan, claimed self-defence. Oakes’s body was found unarmed.

One witness at the trial testified that Morgan had proclaimed open season year-round for “coons, foxes and Indians.” Another testified that Morgan was, in fact, a “wonderful, fine person”. The charges against him were eventually reduced from murder to manslaughter. Then Morgan was acquitted entirely.

For Oakes’s children, the legacy of Alcatraz has been difficult to grapple with. “Lost” is how younger daughter Fawn Oakes describes herself growing up. Born after the Alcatraz protest, she was too young to retain any memories of her father, and yet, expectations for her were high.

“He was there for everyone else but me,” she remembers thinking. Her older brother Leonard, on the other hand, was present for the Alcatraz occupation – but he was only three. He remembers very little. The significance of that time period only hit him at age 13, after he found his late father’s suitcase, brimming with newspaper clippings and documents.

“In the beginning of the occupation, in the beginning of this whole ordeal, I didn’t know who I was. I didn’t know what I was,” Leonard says. But later, understanding what happened at Alcatraz gave him “a sense of identity. It gave me a sense of clarity in who I am and what I’m here for.”

As for Fawn, returning to Alcatraz has been part of her healing process. It has helped her come to terms with her family’s grief – and develop pride in her father’s work.

“People say Alcatraz is not an island. My father used to say it was an idea, an idea of becoming who you are: Becoming self-sufficient. Becoming Native. Becoming strong in your community. An idea to help one another. Not just on the island but when you go home,” she says.

Returning to the island

Many of the original occupiers did take that legacy home. Alcatraz veterans popped up at Fort Lawton in Washington state, where they took hold of a disused army base. They appeared at Pyramid Lake, Nevada, carrying water from around Alcatraz to protest against the draining of the lake.

Occupations arose from coast to coast, from Pit River, California to Washington, DC, leading then-President Richard Nixon to declare an end to federal termination policies.

But the “Indian future” determined “by Indian acts and Indian decisions” that Nixon promised never truly materialised. And even now, Eloy Martinez discerns a flicker of panic when he tells Alcatraz employees he has returned to “reclaim the island”, now a national park.

For years, Martinez has helped lead efforts to preserve the occupation’s history and restore what evidence remains. He often enlists Indigenous youth to repaint the slogans he and other occupiers stamped on the wall in 1969. Richard Oakes’s grandson even found one spot on the ceiling where Martinez wrote his name using the smoke from a votive candle.

That commemoration work has not always earned Martinez respect. It took stubborn lobbying to launch the programmes and exhibits that exist on the island today. And even then, Martinez recalls one former federal marshal who threatened him for promoting the occupation’s history.

“He pointed to me and said, ‘I want to tell you something.’ He says, ‘If Nixon and [White House adviser Leonard] Garment hadn’t ordered a stand-down in 1969, I would have blown your a** out of the water.'”

But Martinez remains undeterred. The way he sees it, the original occupiers set out to build an Indigenous cultural centre, and it exists today on Alcatraz. Lands, rights, treaties, freedom – it all can be stripped away. So 50 years on, Martinez is determined to spread the one thing no one can take away: Education.