Exxon Valdez spill effects linger 25 years on

Massive oil spill disaster continues to haunt the people and wildlife of Alaska more than two decades later.

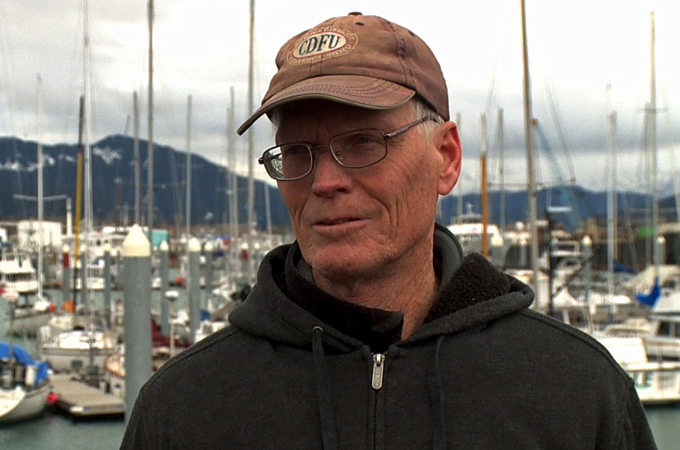

Seward, Alaska – March 24, 1989 is a day that Bob Linville will never forget.

“When we heard on the radio that an oil tanker, the Exxon Valdez, had run aground, we just knew it was bad, that everything was going to change,” said the 61-year-old commercial fisherman.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsThe Alabama town living and dying in the shadow of chemical plants

How India is racing against time to save the endangered red panda

Canada wildfires spur evacuation orders, warnings: What you need to know

For Linville himself, that meant tying up his fishing boat and joining efforts to stop the fouling of Alaska’s rich southern coastal waters. The ruptured hull of the supertanker began spewing crude almost immediately after it grounded outside the port of Valdez – more than 40 million litres of sticky, toxic goo.

“They hired everyone and anyone to help clean up,” said Linville. “The fishing was closed so they had to do it. We all joined in.”

As the slick spread west and south along Alaska’s coast, Linville and others were sent to beaches to rescue animals coated with oil. Later he helped lay floating barriers and tried to scrub oil from the shore with soap. Some crews sprayed boiling water on rocky beaches, while others used dispersants to thin the oil coating.

Medical bills

Linville said one of those chemicals is probably to blame for the decades of mysterious, persistent ill-health he has suffered from since the oil spill. “I got what turned out to be an autoimmune disease,“ he said. “Eventually my bone marrow failed, I got aplastic anaemia, I had two or three other complications. Really, it was like 16 years of illness for me, physically.“

|

| Bob Linville has suffered from chronic health problems since the Exxon Valdez oil spill [Al Jazeera] |

He said he has received no compensation for years of lost livelihood and steep medical bills. “I‘m not the only one that got sick. There‘s lots of others. I‘ve only met a handful at events where we talked about it here locally. But there‘s a lot of people that got sick, and I don‘t think they got any help at all.“

Exxon Mobil, the energy company that owned the leaking tanker, was harshly criticised for its response to the spill and spent years fighting lawsuits filed by the many thousands of people who lost livelihoods.

At times, even the courts seemed to be against the victims of the disaster. In 2008, the US Supreme Court reduced the amount of money the oil giant had to pay in punitive damages from $4bn to about $500m. In its defence, Exxon pointed out that it spent $1bn cleaning up after the spill and paid out twice that amount in settling other legal claims.

For oil spill consultant Rick Steiner, a scientist from the University of Alaska at Anchorage, the very term “clean-up” is fraught with difficulty. Like Linville, Steiner was involved from the first days after the spill in trying to stem the toxic tide of crude oozing from the supertanker‘s ruptured hull.

He became a global authority on such disasters and recently worked on the Deepwater Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2012. He likes to show off a small jar of greasy pebbles, which he carries around in his pocket.

“This is beach gravel from Eleanor Island,“ Steiner said, pointing out to Prince William Sound. “It‘s covered in oil from the Exxon Valdez, 25 years on, and I didn‘t have to dig very deep to find it. I dug it up earlier this year.“

Steiner said the oil industry in Alaska takes the possibility of spills much more seriously than it used to, but there are no guarantees. “We can do better at reducing the risk. But once oil has spilled, you cannot clean it up, you cannot restore an oil-injured ecosystem and you can‘t adequately rebuild human communities that are unravelled by these big industrial disasters.“

Bringing marine back to life

The spill’s toll on wildlife was enormous. Bald eagles, gulls, killer whales, seals and sea otters died in the tens of thousands. Those who survived a coating of oil had to be cleaned and often nursed back to health.

That’s how veterinarian Pam Tuomi became Alaska’s leading expert on sea otters. A few months spent rescuing the iconic marine mammals in 1989 eventually led to a career as a researcher and otter doctor.

|

| Alaska’s southern coastal waters are home to rich fisheries [Jet Belgraver/Al Jazeera] |

“Here’s Agnes. She’s six months old,” Tuomi said, introducing a surprisingly large otter in a pool at the Sealife Centre in Seward.

The animal gave a high-pitched squawk as she was fed, floating on her back and chewing chunks of fresh squid. Brought to the centre as a newborn orphan, Agnes will soon go to an aquarium in Portland, Oregon.

“We saved about 350 otters in three months [in 1989],” Tuomi said, “and we learned a lot about how they cope. The oil was one thing, but we found out about other diseases and issues, and what we needed to do to restore a healthy wild population.”

Since then, Tuomi has been involved in rehabilitating marine mammals in southern Alaska, continuing research into their lives and population health. Sea otters are abundant again in Prince William Sound. Some fishermen even consider them rival predators for salmon and prized halibut. But other species haven‘t recovered. Alaska‘s once-booming herring fishery is finished, and local killer whale populations are in danger of dying out altogether.

‘It’s never over’

Rick Steiner calls the spill a “demographic time bomb” for animals in the affected area.

“Some of these injuries persist. And industry rhetoric aside, we know these disasters do cause long-term, permanent environmental damage. And that’s one of the take-home lessons from Exxon Valdez a quarter of a century later: Once it happens, it’s never over.”

Bob Linville agrees. After a bone marrow transplant in 2006, he has been feeling better and is involved in commercial fishing again. But every March 24, he remembers the day that changed everything and the long ordeal that followed. “I support oil extraction in Alaska,” Linville said, “but I don‘t think sometimes the oil industry gives any credit to the damage they can do“.

He stood still and looked at a ship loading up with coal in Seward Harbour. “I just love this coast. I don’t think it’s healed up from this oil spill yet. We can dig on a beach and you’ll find oil in 10 minutes. It’s going to take hundreds of years to recover.”