Undocumented in US have few protections from virus fallout

Millions of undocumented immigrants in the US face elevated health and financial risks from coronavirus.

Since coming to the United States from Bolivia 20 years ago, Ingrid has eked out a living cleaning houses in the Washington, DC area to support herself and her son and to send money to her mother back home.

The 57-year-old usually earns around $1,500 per month. Nearly half of it goes to her share of the monthly rent on an apartment she shares with her 27-year-old son in Virginia.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsMexico’s teachers seek relief from pandemic-era spike in school robberies

‘A bad chapter’: Tracing the origins of Ecuador’s rise in gang violence

Why is the US economy so resilient?

Even in a good month, Ingrid has very little money to spend on food, utilities and remittances to her family. So when she suffers a health setback, the blow is both physical and financial.

Once she paid $280 out of pocket for an ambulance after a bad fall, she told Al Jazeera.

But that hit could pale in comparison to the risks the coronavirus outbreak poses to her health and economic wellbeing.

“We, more than anything, fear this because we don’t have health insurance, we don’t have paid sick days as domestic workers,” Ingrid, who asked to use only her first name because she is undocumented, told Al Jazeera in Spanish. “Like any human being, we count on having our pay to survive.”

Wall of worry

More than 800 people in the US have died from COVID-19 to date, while the number of confirmed cases has surpassed 55,000, according to Johns Hopkins University.

On Tuesday, the World Health Organization warned that the US could become the new epicentre of the pandemic, citing the very large acceleration of cases.

The crisis has led many governors in the US to declare a state of emergency, including in the state of Virginia, where Ingrid lives.

In response, Ingrid said eight of her 12 regular clients have cancelled her cleaning services for the month of March without paying her. Nor did they say if they will hire her back in April.

This week, she has just three cleanings scheduled, for which she’ll earn about $300 in total, less than half of her $700 portion of the rent is due on April 5.

“A lot of the people we work for don’t understand that we have budgets, we need money to pay our rent, our food and our debts,” Ingrid said. “It’s very difficult for us.”

Ingrid is not scaling that wall of worry alone.

Some 95 percent of the undocumented immigrants or relatives of undocumented immigrants surveyed by the California-based Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights this week said they were worried about paying their bills, while 73 percent said they were worried about contracting the virus itself.

Some 10 million to 12 million undocumented immigrants are believed to live in the US. Many earn their living as domestic workers, or in the restaurant, service or construction industries – sectors of the economy that have ground to a halt as mandatory stay-at-home orders have taken effect.

Ingrid said her clients don’t seem to realise that when they text her to cancel her services, they are derailing her financially.

Immigrants who are undocumented are really scared, and rightfully so.

Little relief, but plenty of fear

It is unclear what, if any, government support tax-paying undocumented immigrants might receive to help them cope with the fallout from coronavirus.

Congress is moving closer to passing a massive $2 trillion economic stimulus plan that could see some US families receive a one-off cash handout of up to $3,000.

But it is not yet clear whether that measure would exclude people who pay taxes using individual taxpayer-identification numbers – a common practice for immigrants without Social Security numbers, according to immigrants’ rights group Make the Road New Jersey.

While the federal government has waived testing costs for coronavirus, treatment is not universally free.

For undocumented people like Ingrid, that means contracting coronavirus could be financially ruinous.

“Because we don’t have health insurance, we take care of ourselves at home with the medicines we can buy in the pharmacy without a prescription,” she said. “Or we have to go to medical centres that charge us a lot.”

Where she lives, that means shelling out about $70 – plus any testing or drug costs, Ingrid said.

Activists also warn that the anti-immigrant rhetoric and climate of fear created by the administration of US President Donald Trump could make undocumented people less likely to seek testing or treatment for fear of being arrested or deported, potentially accelerating the virus’s spread.

“Immigrants who are undocumented are really scared, and rightfully so,” Julie Kashen, senior policy adviser for the National Domestic Workers Alliance, told Al Jazeera. “That means that they are less likely to seek healthcare when they need it, and it means that they are less likely to be able to do what they would need to care for themselves and their family.”

“Even if there are provisions in place to make sure that they’re not supposed to be legally retaliated against or that ICE [US Immigration and Customs Enforcement] isn’t supposed to be called, there’s no reason for them to trust that in this moment, when there’s been such an unfair and unsafe situation,” she added.

ICE, the government agency tasked with arresting and deporting undocumented immigrants in the US, said it does “not conduct operations at medical facilities, except under extraordinary circumstances”.

In response to the pandemic, ICE announced it will allow discretion over whether an arrest or deportation operation can be delayed, with a focus on “public safety risks and individuals subject to mandatory detention based on criminal grounds”.

But even as residents are urged to stay inside, ICE agents are still making arrests.

Agents brought masks for an operation in California after the state’s governor put people there on lockdown last week, the Los Angeles Times reported.

And not all undocumented immigrants who are mandated to check in at ICE field offices have had their appointments rescheduled, despite social distancing guidelines from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

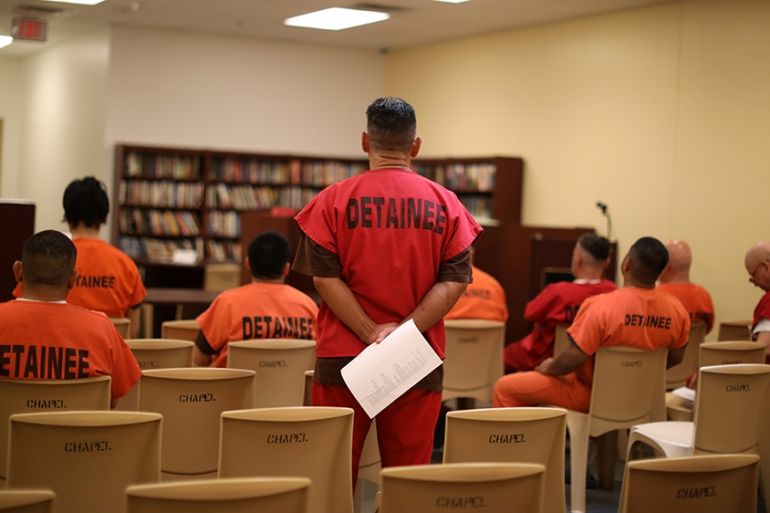

Concerns are also growing about the health and safety of people being held in immigration detention facilities.

On Tuesday, ICE said a 31-year-old Mexican national being held in Bergen County Jail in Hackensack, New Jersey had tested positive for COVID-19.

ICE also said that one of its employees in a detention facility and 18 not assigned to detention facilities had tested positive for the disease.

On Tuesday, The Nation magazine reported that it had obtained an internal US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) report dated March 19 that said nine undocumented immigrants held in ICE facilities had been isolated for medical reasons and that two dozen more were being monitored in 10 more facilities, adding that the title of the memo suggested it was in response to COVID-19.

An ICE spokesperson told Al Jazeera she was “unable to corroborate the information sourced in the article that was allegedly leaked to the reporter”, and that “ICE cohorts individuals for a variety of infectious disease”.

On Friday, two whistle-blower physicians contracted by DHS’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties wrote a letter to Congress warning of a “tinder-box scenario” if the virus is allowed to spread through detention facilities, CNN reported.

There were 37,311 detainees in ICE and Customs and Border Protection facilities as of March 14.

Amnesty International, Physicians for Human Rights and Human Rights First have urged government authorities to “release immigrants and asylum seekers held in administrative detention by ICE” due to the “documented inadequacies of medical care and basic hygiene in immigration detention facilities”.

The groups also warned that infections in facilities could easily spread beyond them.

“The coronavirus is really hitting home the ways that we’re all so interconnected and living in such a community, no matter who we are – whether we’re somebody who moved to the United States with papers or without,” said Kashen. “Public health requires that we all care about each other to save lives.”

Ingrid agrees.

“I wish people would have a little more consideration for us, because we are the people, in reality, who help them with their children, with their older people, with their homes,” she said. “We are the people who help them live their lives.”