The new race to the moon is not just about bragging rights

Like the 20th century moon race, the 21st century one is projecting geopolitics beyond the limits of our atmosphere.

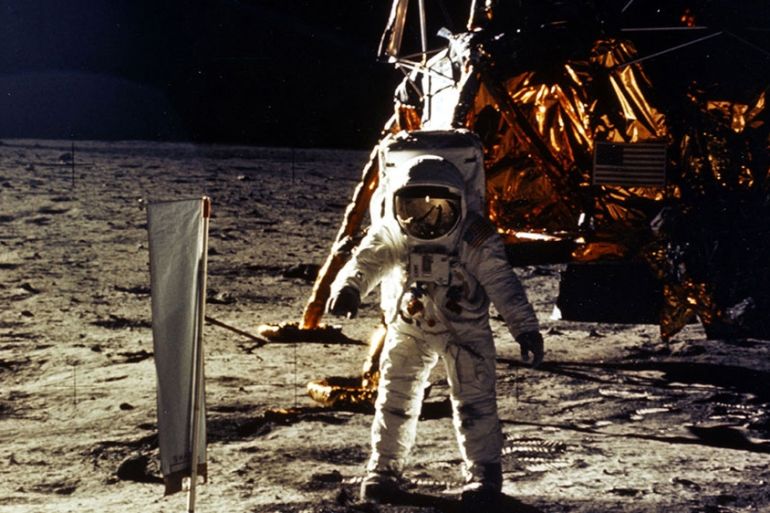

Fifty years after the blastoff of the Apollo 11 mission, which successfully delivered humans to the surface of the moon for the first time, a global race is in hyperdrive to stake both national and commercial claims to the lunar surface – and to what’s below and even beyond it.

This week, India postponed the launch of Chandrayaan-2, the nation’s second uncrewed mission to the moon. If it ultimately proves successful, India will join a very exclusive club of space-faring nations including the United States, Russia and China, which have landed – not crashed with or without intent – on the moon.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsBoeing postpones launch of Starliner space capsule after technical fault

China launches Chang’e-6 probe to study dark side of the moon

China launches historic mission to far side of the moon

But the stakes with such missions go far beyond bragging rights. They are stepping stones to getting humans back on the moon – a feat the US, China and Russia have announced they plan to achieve by 2024, 2025 and 2030, respectively.

And it’s not just major powers. India, Japan and Israel also want to be a part of putting human outposts on the lunar surface.

Like the 20th century Cold War space race between the US and the Soviet Union, the 21st century competition is projecting geopolitical, economic and commercial interests well beyond the limits of our atmosphere. But this time around, it’s not just national pride and a military advantage that is at stake, but potentially hundreds of billions of dollars to be won in a new space-age gold rush.

Where there’s water, there’s competition

Nations and the space-related private corporations that fall under their flags are competing for a piece of a commercial space industry that the US Chamber of Commerce estimates will be worth $1.5 trillion by 2040.

It’s not just the moon’s proximity to Earth that makes it an attractive foothold for spacefaring nations, but what’s on its surface.

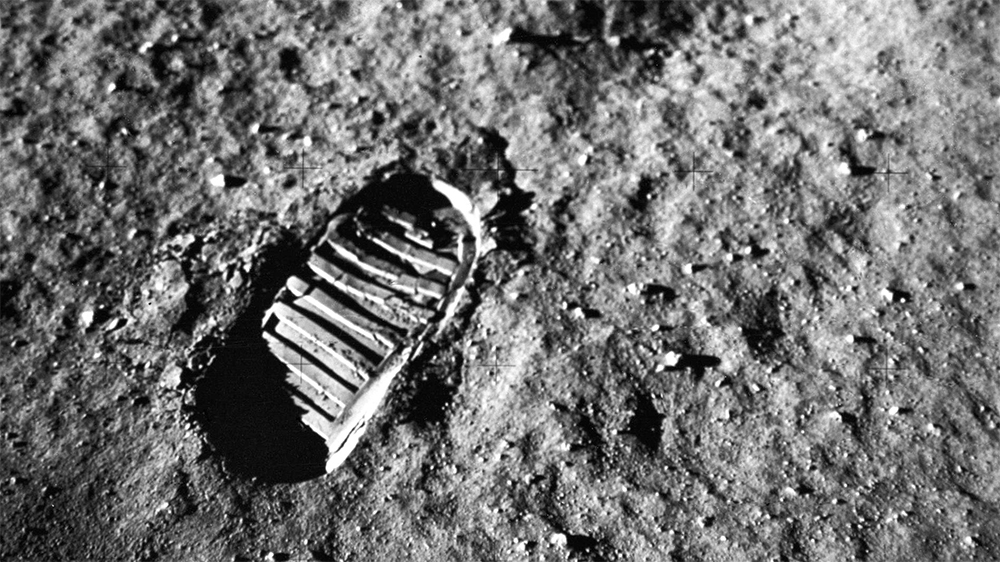

Though the US was the first country to land humans on the moon, the astronauts on that Apollo missions didn’t see what India’s Chandrayaan-1 uncrewed spacecraft unveiled in 2008: evidence of water in the moon’s craters.

That discovery was literally a watershed. As commercial space entrepreneur, Amazon founder and world’s richest man, Jeff Bezos recently noted, water dramatically enhances the strategic importance of the moon as a platform for space exploration.

“We know for sure now there is water on the moon in the form of ice in the permanently shadowed craters on the poles,” Bezos, the founder of private space exploration company Blue Origin, told host Caroline Kennedy during a fireside chat at last month’s JFK Space Summit in Washington, DC.

In May, Blue Origin unveiled a full-scale model of its Blue Moon lander, which it hopes will deliver crews back to the moon’s surface. Blue Origin is developing an engine for Blue Moon called B-E7 that’s powered by hydrogen and oxygen, the building blocks of water (H2O).

“We can harvest that ice and use it to make hydrogen and oxygen, which are rocket propellants, high-performance rocket propellants,” Bezos explained at last month’s space summit. “The reason we chose those propellants: A) they are the highest-performing propellants, but B) we know one day we’ll be refueling that vehicle on the surface of the moon from propellants made on the moon from that water ice.”

Another element believed to be abundant on the moon’s surface – which could further enhance its appeal as a location as a refueling hub – is helium-3, an energy-producing isotope that could power future fusion rockets.

Chandrayaan-2 – which means “moon vehicle” in Sanskrit – is supposed to deliver a robotic rover to the South Pole of the moon to search for sources of water and helium-3.

And India is not the only nation trying to get a better handle on the riches that could reside on the moon’s surface.

In January, China made history when it became the first country to successfully set down a lander, the Chang’e-4, on the far side of the moon at the South Pole (India is endeavoring to land on the South Pole on the near side).

China is expected to launch the Chang’e-5 mission before the end of the year to bring samples from the moon’s surface back to Earth for the first time in four decades.

And Beijing’s future Chang’e-6 lunar mission aims to include an orbiter, a lander, an ascender and a return capsule.

The moon gold rush

Extraterrestrial cooperation between competing space-faring nations is nothing new. US astronauts have been riding to the International Space Station from Russia’s Cosmodrome since NASA retired its Space Shuttle in 2010.

India’s Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft carried NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper, which was instrumental in discovering water on the lunar surface.

And in April, China announced that it wishes to take payloads from other organisations – including private enterprises and foreign scientific research institutions – on its Chang’e-6 mission.

Still, political realities on Earth are placing limits on off-planet cooperation.

NASA, for example, cannot cooperate with Chinese agencies without getting approval from the FBI and notifying the US Congress. This provision, which is included in US spending bills, is the evolutionary result of earthbound strategic geopolitical frictions over territory, resources, trade and technology that have been steadily intensifying for decades.

“I think what we see today [is] that the global landscape is clearly structured by competition and cooperation,” said Jean-Yves Le Gall, president of the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES), also known as the French space agency. “Competition between China and the US, it is not the same as the one that we knew 30 years ago between the US and the USSR.”

This time around, the moon race is marshalling both public and private-sector capital in an effort to claim resources – and eventually establish human-occupied outposts. But it does carry echoes of the 19th century American gold rush, where players saw an advantage in staking claims first so they could write the rules of the game.

China’s aggressively-paced lunar programme is believed to have spurred the US in May to change its date to return humans to the lunar surface, moving it up to 2024 from 2028.

“It is clear that all the announcements which have been made recently by the US, in particular to accelerate the moon programme, [are] probably a consequence of a very strong development of China projects,” Le Gall told Al Jazeera. “And if the US wants to be the first ones to be back to the moon, it is because they want to set the rules.”

That very reasoning was expressed by US Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross in April at the 35th National Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

“As more countries land on the Moon, we risk a ‘Wild West’ situation without clarification of ownership rights,” said Ross. “We need to ensure that those who extract crater ice at 40 degrees above absolute zero, and other resources, will keep the full economic results of their development. Having [the] US be the first permanent presence on the Moon will help create such conditions.”

It’s not just US officials invoking the same reasoning. Ye Peijian, head of China’s lunar exploration programme, explained the stakes in a candid statement during one of the Chinese Communist Party’s 2016 plenary sessions, when he equated his nation’s space ambitions to its policy of asserting supremacy in the South China Sea.

“The universe is an ocean, the moon is the Diaoyu Islands, Mars is Huangyan Island,” Ye said. “If we don’t go there now even though we’re capable of doing so, then we will be blamed by our descendants. If others go there, then they will take over, and you won’t be able to go even if you want to. This is reason enough.”