Space 2019: What a year, what a decade we’ve had!

On the ground and in orbit, this year saw geopolitical competition, mega-constellations – and women in space.

It was a year of momentous events in the space sector, to be sure, but 2019’s true significance may ultimately be that it was marked by geopolitical and commercial competition that, for the past decade, has been slowly simmering up to an estimated $400bn economy.

“I think the biggest development in this decade has been [the] return of great power competition in outer space,” Frank Rose, a former United States assistant secretary of state for arms control and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told Al Jazeera.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsRussia’s Angara A5 rocket blasts off into space after two aborted launches

Photos: Mexico, US, Canada mesmerised by rare total solar eclipse

Moment total solar eclipse occurs in North America

These mighty crosscurrents have created an urgency, not seen in decades, that is compelling nations and luring Wall Street to bank on commercial space actors large and small – and launching the space sector into what could be a multitrillion-dollar industry by 2040.

The moon race

There’s more than a pinch of deja vu here. In the Cold War era, the former Soviet Union and the US invested treasure and national pride into being the first to have astronauts stroll amongst the moon’s dust-covered craters. The new race is about staking and maintaining claims on high-value lunar resources: water and rare-earth minerals.

![Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin works on a solar wind experiment device on the surface of the moon. [File: NASA/AP Photo]](/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/9625c1115d81415aa420f7b8eac788c3_8.jpeg)

The decade opened with China announcing its aim to land astronauts on the moon in 2025. In 2019, 50 years after the Apollo 11 mission, the US administration countered by setting 2024 as its crewed moonshot deadline.

The next decade is starting without a US-made spacecraft certified for human spaceflight, but NASA has tapped two commercial partners, Boeing and SpaceX, to change that status in the first half of 2020. US President Mike Pence said that by then, the US would again launch astronauts into Low Earth Orbit – a first since NASA’s space shuttle fleet was decommissioned in 2011. After a series of setbacks, neither space company has committed to that timeline.

However, it was in January that China’s Chang’e-4 lunar lander mission to the South Pole set the year’s pace. While it was that nation’s second successful lunar landing – the first being in 2013 – it was the first time any nation had touched down on the far side of the moon. Nevertheless, China still has a lot to prove. The rising space power should end the year with the third test of its mammoth rocket, the Long March 5, the last launch of which failed in 2017.

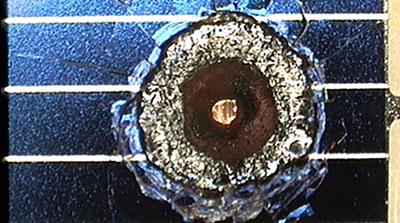

Vying for a piece of the moon pie, Israel’s Beresheet lander in April shattered when it smashed into the moon’s southern polar region. Six months later, in September, India‘s Vikram lander – part of the Chandrayaan-2 mission – became the latest lunar fatality.

Militarisation

It was in 2019 that Western nations took action to meet what they perceive as a growing economic and security threat from Russia and China, which they accuse of developing anti-satellite weaponry.

The fear is that if certain satellites are destroyed, economic sectors dependent on satellite communications and imaging – such as air traffic control or weather prediction – could be decimated. Or worse, a nation’s military surveillance systems could be blinded from detecting an attack.

In July, France announced it was establishing its “Mastering Space” weapons programme with the intent of providing its military with on-orbit space assets capable of surveilling and targeting its adversaries with active measures.

One month later, the US launched Space Command, the forerunner to what will be the sixth branch of the military: the US Space Force, which the US Congress just authorised on December 17.

Earlier in December, NATO’s 29 heads of state declared space “the fifth operational domain for the alliance, alongside land, air, sea, and cyber”. This could mean that if one ally’s satellite is attacked, NATO members would then take all necessary measures, including the use of force, to defend that ally and the alliance.

“Effective diplomatic efforts could serve as an important complement to military efforts, but it remains to be seen whether the Trump administration will pursue such efforts,” said the Brooking Institution’s Rose.

Mega-constellations and space trash

Space is a big place, but this year, governments and space agencies responded to the threat of business-killing collisions posed by mega-constellations and pieces of space debris, circling the earth at armour-piercing speeds.

While SpaceX has already placed 120 satellites into orbit for its Starlink system, and OneWeb has just six, according to licencing filings, that number is set to mushroom. As an example, SpaceX has a licence to launch and deploy 12,000 satellites for its network but is seeking permission for 30,000 more. Yes. That could mean a total of 42,000 satellites from SpaceX alone.

This year, the US government updated its Orbital Debris Mitigation Standard Practices guidelines with a new section specifically addressing satellite constellations.

Across the Atlantic, the European Space Agency signed a $129m contract with the Swiss startup ClearSpace to remove a 100kg piece of junk from orbit. Launching in 2025, this commercial removal mission will be the first of its kind.

Daniel Ceperley, founder and CEO of the debris-tracking services company LeoLabs, said that next year, “there will be increased awareness of the collision risks created by derelict satellites and rocket bodies”.

“We see multiple near misses every week,” he said, “with derelict satellites passing within one hundred metres of one another.”

Talent shortage challenges the ‘bro’ network

Space Angels, a space industry investment platform, announced in its third-quarter report that total new funding for the first nine months of the year “reached $5.0bn, putting 2019 on track to be the largest year on record for Space investment”.

Facing an acute labour shortage, the report’s authors argued that commercial space companies “must attract talent to sustain their growth”.

Women space leaders argue that a talent pipeline already exists, while labour experts say an entrenched “bro” culture continues to deter many women engineers and scientists from seeking careers in space.

Charity Weeden, vice president for global space policy at the satellite services and space debris removal technology firm Astroscale, told Al Jazeera, “Overall, this year has been one of mixed messages for women in the space industry and space community at large. When women succeed in this industry, people still downplay those accomplishments.”

She added, “Studies are showing that having a gender-diverse work environment leads to better results and revenue. So if you’re not including women because it’s the right thing to do, then maybe you’ll do so for the profit.”