Turning the page for feminism

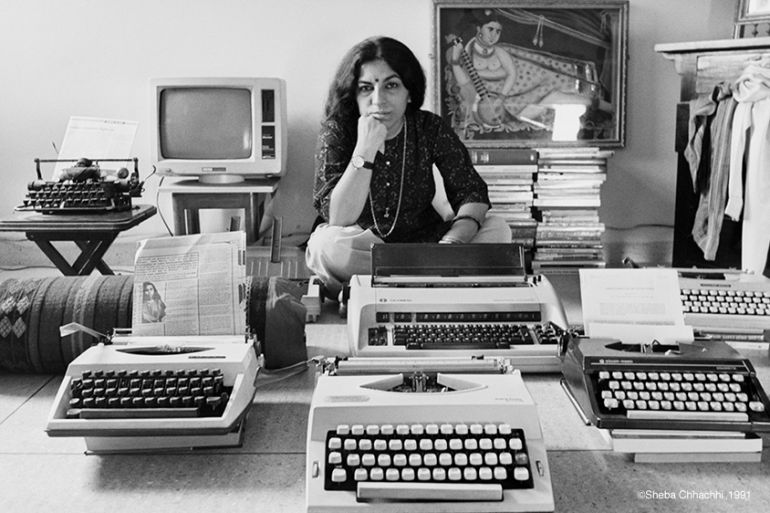

Indian publisher Urvashi Butalia has given women and marginalised voices a platform for over three decades.

To reach Zubaan, the feminist press founded and run by Urvashi Butalia, visitors and authors walk through the winding lanes of Shahpur Jat.

This is one of Delhi’s older urban villages.

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsA Greek woman feared her ex-partner. He killed her outside a police station

Nigeria’s women drivers rally together to navigate male-dominated industry

Members of London’s Garrick Club vote to let women join for first time

The crisp window displays of fashion and furniture shops have learned to coexist with small home industries and pragmatic grocery stores, sturdy glass jars of crumbling salty biscuits displayed on their formica counters, as neighbourhood children play ferociously good cricket in the narrow alleys.

Everyone in the lanes leading up to Zubaan knows the “Publisher Didis” office; there are no daunting glass-fronted entrances, no watchful doormen to keep the press apart from its neighbours. Inside, the walls are lined with an assortment of bookcases – metal, wood, glass-fronted, open-shelved – containing an equally eclectic history of women’s lives and feminism in India.

Zubaan, founded in 2003, is Urvashi Butalia’s second publishing venture: in 1984, she set up India’s first feminist publishing house, Kali for Women, with the scholar and publisher Ritu Menon. Taken together, these two publishing houses contain the collective memory of much of the Indian women’s movement – written in memoirs, biographies, fiction, academic studies, histories, and more.

In the 1980s, anti-dowry agitations and campaigns against domestic violence and rape focused attention on the high numbers of women for whom marriage was a battlefield, often a deadly one.

The late 1980s was marked by the campaign against the resurgence of sati after 18-year-old Roop Kanwar burned herself on her husband’s pyre, and agitations against legislation that significantly weakened the rights of Muslim women in divorce cases.

The 1990s saw the rise of Dalit feminism and a greater focus on caste inequalities and gender, growing concern over the practice of female foeticide and infanticide.

Among grassroots groups, long-running battles over basic healthcare, land reform, forest access rights, fishing rights and other issues fed into labour and environmental struggles all through the 2000s.

Concerns over the growing acceptability of violence against women – in their homes, in workplaces and public spaces, in conflict zones, by fundamentalist and communal forces – fed directly into today’s ongoing debates on women’s freedoms and the attempts to truncate those freedoms in the name of safety.

Through these tumultuous times, Zubaan and Kali for Women functioned also as archivists and as participants in the organically evolving network of disparate groups that formed the Indian women’s movement.

“We’re putting together an archive of the interviews we’ve recorded with authors, organisers, women on the front lines,” Urvashi says.

Recorded over the decades, these will be an invaluable oral history of Indian women, many of them far more focused on getting the job done in any given moment than on chronicling their thoughts.

A very exciting time

The roots of Urvashi’s feminism stretch back to her childhood. She was born in 1952, and grew up in the town of Ambala in Punjab, moving to New Delhi in 1961.

Her mother ran the house and taught in college, earning the modest sum of Rs 300; she also gave her children a brisk understanding of their father’s gambling problem from an early age. These were the post-Partition decades; Mrs Butalia had to handle a constant flood of relatives and extended family. “The hospitality of the household was extended to anyone who visited,” Urvashi says. “I worried about the burden she carried.”

Urvashi’s grandmother lived with them. She was “conventional, saw her daughter-in-law as someone to be oppressed, an upstart who had arrived with no dowry”.

At mealtimes, she insisted that the men – uncles, brothers, cousins – would be served first. But in the afternoon when the old lady was asleep, the girls would steal the keys to the large tin trunks where she stored dry snacks – papads, shakkarpadas.

“My mother encouraged us to help ourselves. She said that there was no way her girls were going to eat less in her house. I didn’t have a word for it, I didn’t know the word ‘feminism’ then, but I learned from my mother that there was nothing natural about discrimination, and that it had to be fought.”

Urvashi went to college in Delhi. In the 1970s, Delhi University provided an excellent introduction to the real world of politics. The peasant revolt of 1967 in Naxalbari had jolted West Bengal and the rest of India, and campus discussions revolved around the politics of class struggle. Many left to join grassroots movements that tackled issues invisible to urban India. The women’s movement in India was putting down roots.

“We discussed feminism, we were naïve but intense,” Urvashi recalls. “But Delhi University was in the grip of Naxalbari, it was a hotbed of political discussion. Friends of ours often disappeared” – dropping out of their studies – and “got involved at a deeper level.”

This was a far better education than the one provided by the antiquated, colonial syllabus.

“Milton and Spenser” – the 16th and 17th century English poets whom undergraduates were supposed to study – “had nothing to do with the sexual harassment we faced every day on the roads, on the buses.”

Urvashi and her friends began to question the basics of college life in India. It was a confusing time – she remembers participating as a “fresher”, a new student, in a beauty contest. “Our seniors made us wear saris, high heels – we walked the ramp, but I remember feeling something wasn’t quite right there.”

My mother encouraged us to help ourselves. She said that there was no way her girls were going to eat less in her house. I didn't have a word for it, I didn't know the word 'feminism' then, but I learned from my mother that there was nothing natural about discrimination, and that it had to be fought.

There were more pressing problems. Conditions for women students were deplorable; their presence on campuses only grudgingly tolerated. Men had more freedom, more space – a far greater number of hostel rooms were allocated to male students – and more relaxed curfews, discriminatory practises that continue to this day. Urvashi stood for student elections, representing her college, the all-women Miranda House.

They campaigned successfully for separate buses for women (segregated Ladies Specials, intended to allow women to travel without fear of assault or stalkers), and managed to ease some of the restrictions on women hostellers’ movements around and outside campus.

Urvashi’s generation of women were inspired by many activists, academics and thinkers whose history of engagement stretched back to the days of the Indian nationalist movement – Vina Mazumdar, Leela Dubey, Lotika Sarkar, Vimla Farooqui and many others.

This was also the decade when women’s groups started to band together.

“In Delhi, we were talking to and helping women deal with dowry cases, working on landmark changes in the laws with the Law Commission. I don’t know how we ran campaigns without the Internet, without working landlines; women wrote letters, went by bus to different towns. It seems incredible now.”

In 1974, the scholars Vina Mazumdar, Kumud Sharma, and CP Sujaya released a landmark report, Towards Equality. Urvashi learned a valuable lesson from the Indian educationist JP Naik, who told the group to immediately hold a press conference when releasing the report, rather than allowing political or government interference.

It was the first post-Independence document to address women and their rights, and it set the template for the Indian women’s movement over the next few decades. “It was very exciting – a very full time,” Urvashi recalls.

Breaking into a man’s world: publishing

She had finished her Master of Arts, and it was expected that she would take up teaching – one of the few jobs considered suitable for women in that era. It was hard to imagine becoming a publisher, in a world where women didn’t join or run publishing houses.

“But I had dreamt of becoming a printer,” Urvashi says. “I wanted to print political pamphlets for friends in various movements.”

So Urvashi joined Oxford University Press (OUP) on Ansari Road, located in Daryaganj in Old Delhi, at that time home to many academic publishers and secondhand bookstores, as a “paster-upper”.

The OUP’s Active English series, produced in Hong Kong, needed to be Indianised for local schools – publishing houses, run for many decades by English men, were slowly Indianising. “My job was to replace ‘John & Mary’ with ‘Ram & Sita’.” She worked alongside an artist, Dean Gasper, who coloured blonde hair black, and painted over the tops of double-decker buses – most Indian cities had only single-deckers. Within four months, she was “completely in love” with publishing.

Then she landed a real job in the production department and began visiting all the printing presses – some in central Connaught Place, others located in relatively distant colonies such as Mayapuri, in West Delhi. Many presses – the venerable Thomson Press, the Rekha Press – were not used to women making the rounds, especially not women in their twenties.

Her boss, Adrian Bullock, insisted that she learn as much as she could about book production. “When the presses found that I was knowledgeable about printing, I received a little grudging respect,” she says. “And invitations to coffee at Rambles in Connaught Place, which I steadfastly declined!” For women in the workplace in the 1970s, fending off unwanted and often unprofessional male attention in an age before sexual harassment rules were instituted was, unfortunately, a common hazard.

She liked getting her hands dirty, liked the smell of printer’s ink; it meant a lot to have the approval of printing veterans like ML Gupta at Indraprastha Press, who said she was a veritable “ustad” or “master” of printing. Her next bosses, Charles Lewis and then Ravi Dayal, were equally open and generous. She spent a lot of her time in the paper market, Chawri Bazaar, in Old Delhi as well: “Those six years gave me a very solid start.”

Looking back, though, there was a limit to what Urvashi could learn from her male bosses. “They were so helpful in shaping me as a publisher,” she says.

Bullock insisted that she learn how to do costings; she discovered that she had a flair for calculations, the intricate business of paginating editions, working out paper and printing costs, print runs. Ravi Dayal generously gave her projects to edit when she said she thought she’d like to do some editorial work.

‘I’ll do it myself’

“But it was also the fact that they never considered women worth publishing that made me more determined to start my own house,” Urvashi says.

One of her bosses asked: “But what do women write?” when she raised the subject.

He was not being condescending. “They literally didn’t see women as authors, didn’t see women’s writing. I thought, if they can’t do it, I’ll do it myself.”

Meanwhile, India was heading into one of its most turbulent periods: Indira Gandhi imposed a state of emergency that lasted from 1975 to 1977, declaring that there was a threat to national security, after she had faced a case accusing her of electoral malpractices and her government had faced strikes across trade and student unions.

Fundamental rights were suspended; the media was heavily censored, and in the clampdown on basic democratic freedoms, many were imprisoned, while a rash of forced sterilisations and slum demolitions spread unrest across India.

They literally didn't see women as authors, didn't see women's writing. I thought, if they can't do it, I'll do it myself.

Urvashi was away, working in OUP’s cartography department in the UK. She was staying in the London home of Charles and Premila Lewis.

Charles headed OUP at the time and Premila, a social worker, had been organising labourers and encouraging them to demand basic rights on the farms of Mehrauli, which included one of Mrs Gandhi’s properties.

She went back to India from London in 1976 and was arrested as soon as she got off the plane; she would be held in prison for several months.

But though the state clamped down on many political parties, women’s groups were by and large allowed to function. “They arrested and sometimes tortured women who belonged to the radical Left, Maoists, but they didn’t bother with the others,” Urvashi recalls. “We saw what was going on. It fuelled our politicisation.”

Urvashi was part of the original collective that came together in 1976 to form Manushi, widely seen as India’s first progressive feminist magazine in English.

In Urvashi’s recollection, the intentions behind the collective of 18 women, brought together by Vina Mazumdar, were powerful. But with little experience of collective functioning, petty problems surfaced, and the original group soon disbanded.

What she learned from that experience was valuable, though. “We had come together to solve the problems of women, but we never talked about ourselves. It came slowly, the intimacy of sharing, the daily practice of understanding your own privilege and class issues.”

Collecting women’s own histories

By the 1980s, the Indian women’s movement – massive, diverse, made up of groups with very distinct concerns – had begun to grapple with the relative absence of their own written histories. “There was so much published in the West,” Urvashi says. “It was a comfort to have that, but it didn’t explain what we were confronting on the ground.” When they explored dowry killings, for instance, they began to see how these demands and deaths served a functional purpose: they were a way for Indian families to get the capital needed for small businesses, white goods, and home expansions.

Did dowry affect only Hindus, was the practice restricted to the north of India, was it a middle-class phenomenon? The answers were complicated. When families declared that the giving and taking of dowry was voluntary, it raised thorny issues around agency. “We had always seen agency as desirable, but what if women used their agency to demand or enforce violence towards other women?”

Urvashi began to talk about starting her own publishing house: “We needed answers to these questions. The books grew out of this need to collect our own history.”

We had always seen agency as desirable, but what if women used their agency to demand or enforce violence towards other women?

On her way to Hawaii on a Fulbright scholarship to do a PhD, she stopped in London and met friends at Zed Books, a dynamic academic press that specialised in politics, development and gender. An old friend there asked her why she was going to Hawaii: “You can’t swim, you can’t surf.” Instead, they suggested she spend two years working with them.

During that time, she commissioned and edited books and authors for a special list on gender for Zed. The contacts she made in the international publishing world would prove very useful later, when Kali for Women and Zubaan needed to sell rights. In the early 1980s, the scholar Ritu Menon wrote to her, asking if she was looking for someone to collaborate with.

Urvashi returned to Delhi, with plans for Kali for Women alive in her mind. That evening, she stepped out to water the plants on her roof. The gulmohar trees had flamed redly into full bloom and she remembers thinking, “I’ve come home.”

Ritu’s husband painted their makeshift office in the garage yellow and white; the two of them rattled around Delhi, meeting authors, in Ritu’s sturdy black Ambassador car. The books started to come out – a collection of short stories by women called Truth Tales, in seven different Indian languages, compilations of women’s popular songs and protests, a history of the Telangana movement in the south, and radical explorations of the past from a gendered perspective. “We were happy, unpaid, inspired. Those were the better days,” she says.

![An inside view of Sharir ki Jaankari (About the Body), an educational booklet published in 1989 by Kali for Women, continues to sell in the thousands in ration shops and gender workshops [courtesy Zubaan]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/0cf51cc6a6ec4db084e34cd7a2980e7d_6.jpeg)

One of her favourite books from that time is a profoundly influential booklet called Sharir ki Jaankari (About The Body), published in 1989. “I was still wrestling with doubt – was I fooling myself that I was contributing with this publishing business, away from the movement? In retrospect, this was the most important book we published.”

Kali for Women developed a warm and loyal following among women over the years. One day, a group of women dropped by their office – rural women from Rajasthan, bearing a beautiful, handmade, practical booklet on the body. They had tested the book in their workshops. The original version featured an anatomical illustration of a naked body, and the villagers laughed at them: in which village would you see a woman (or a man) roaming around naked?

In the final version, a woman is drawn in a lehenga. Cut-out panels have been pasted on; when you lift them up, you can see the breasts, the abdomen, the uterus, and the same for the man’s body. Seventy-five women contributed; all 75 names are listed on the cover. The book continues to sell in the thousands, but has never been sold in bookshops – it’s distributed through ration shops, gender workshops, local outlets. “The women had one condition: if we published it, every copy sold to a village woman had to be sold at cost price,” says Urvashi.

The other problem they encountered was unexpected. Their regular printer in Old Delhi came to them apologetically, saying he could not print the book – the young boys who worked in his printing press were growing “overexcited”. Instead, one of Urvashi’s colleagues located a women’s printing collective in another part of Delhi, who were able to contain their excitement. They printed it under the condition that they would receive a special box of sweets for every completed print run.

In between the busy humming grind of the publisher’s life, Urvashi found time to write a major history of Partition, conducting interviews with dozens of women over a decade for The Other Side of Silence, which came out in 1998. She tried hard when she spoke to Damayanti Sahgal, Kamlaben Patel, Basant Kaur, her mother, other women who had survived Partition – almost all of them now dead – to build trust, to withhold judgement. Many had never shared their experiences. There had never been a history of the 1947 Partition of India, in which over a million people died and 12 million more were displaced, from the point of view of women.

“It was very moving, but also tragic and sad to see how society tries to silence women in so many ways, and wonderful to see how women subverted this and made themselves heard.” Among their families, they were guarded, but if she joined them in satsangs, gatherings of song and prayers held in gurdwaras, she found they could speak more freely.

Zubaan

After 19 years in partnership, Kali for Women’s founders finally parted ways in 2003. Ritu Menon went on to found Women Unlimited, and Urvashi started Zubaan Books – the word means “tongue” and “language” in Hindi – in the same year. Zubaan has a wider catchment area than Kali had. Urvashi publishes children’s books, mainstream fiction and translations as well, though women’s lives and histories remain at the core of her work.

![Baby Halder, photographed in July 2006, worked as a domestic servant in Delhi for many years, writing about the struggles in her early life in between her chores [Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/4b711dff35eb4c5cb47a65e2a6544fba_18.jpeg)

Four years after Zubaan opened its doors, Urvashi published a book that would change the fortunes of the author as well as those of the firm. Baby Halder’s memoirs, A Life Less Ordinary, was a bestseller that crossed urban India’s rigid class barriers – Halder had worked for many years as a domestic servant, writing in exercise books in between rounds of sweeping, cleaning, and making tea.

“We had been able to publish marginal voices, not as subjects to be reported on, but as the ones speaking out. The book changed her life, for better and worse – it gave her a house, helped her to educate her children, but once you’ve moved out of poverty, class in India is not so easy to transcend.” Baby Halder is still writing; she’s moved to Mumbai where she is a hostel supervisor for a woman’s group. “It’s a delicious irony to me that a book written by a poor woman could help turn our fortunes around,” Urvashi says.

![Butalia published Baby Halder's 'A Life Less Ordinary' [Getty Images]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/84ed8872edae492cb59787b983c599d9_18.jpeg)

Lunch at Zubaan is an egalitarian meal where everyone congregates at the table, the conversation flowing in busy eddies. Right from the start of her publishing career, recognising the burden many women carry as they juggle domestic chores and office work, Urvashi made it a rule that lunch will be provided by Zubaan, freshly cooked by Nirmala, the office canteen supervisor or one of the other women.

A print of Botero’s plump Mona Lisa smiles benignly down at the team on one side; the Rajasthani artist and women’s right activist Radhaben Garva’s bright, intelligent art blesses Zubaan from the other wall.

After her active life in the women’s movement, what changes does she see ahead?

In her view, urban Indian feminism has moved from the street level activism of the 1980s into institution-building, as modes of resistance change; crucially, affirmative action at the village level has brought far more women into political power in rural India.

![Urvashi Butalia at Zubaan, the feminist press she founded and runs in Delhi [Showkat Shafi/Al Jazeera]](/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/bd19a782e7df474cb586133c12c3ecd2_18.jpeg)

Women’s agency

Perhaps the big shift, Urvashi says, is that the issues and choices are more complex, no longer black and white. “Women are much more aware of the greys – the debates we’ve had over religion, communalism, sex-selective abortion, supposed free choice, have made women think harder about these things. For example, there was a time when we assumed women’s agency was an unmitigated good, until women’s claim to religious identity and all that comes with it, including communalism, made us see otherwise and question our own assumptions.”

As Urvashi analyses these shifts, you start to see the Indian women’s movement as a dynamic work-in-progress, rather than a monolith.

“There are also changes in the relationship of women’s groups to the state,” she says. “There’s a realisation that sometimes you have to work with the state. At other times, you might confront it and battle with it, but the relationship need not always be oppositional.

“There’s a lot of questioning of the movement from within and discussions about whether or not the movement has excluded women of ‘alternative’ sexualities, or lower caste women, or whether it has been too majoritarian, too urban.”

All of this is something she views as beneficial, even necessary. But after a lifetime of engagement, Urvashi also sees the vastness of the Indian women’s movement. “There is so much more – how to put it all together?” she writes in an email, looking for and then finding the words.

“Though women still remain second-class citizens in our country, they’re no longer standing outside the door hoping someone will see them, instead they are demanding to be let in and listened to.”

Nilanjana S Roy is the author of two novels, The Wildings and The Hundred Names of Darkness; her essays on reading, The Girl Who Ate Books (HarperCollins), are out this December.

She has written on gender, free speech and the reading life for the Business Standard, The New York Times, the BBC, Outlook and other media organisations. She lives in New Delhi.

You can follow Nilanjana on Twitter at @nilanjanaroy.