Surviving against all odds

Masika helps women and children in DRC to heal the wounds of rape and to hope for a better future.

|

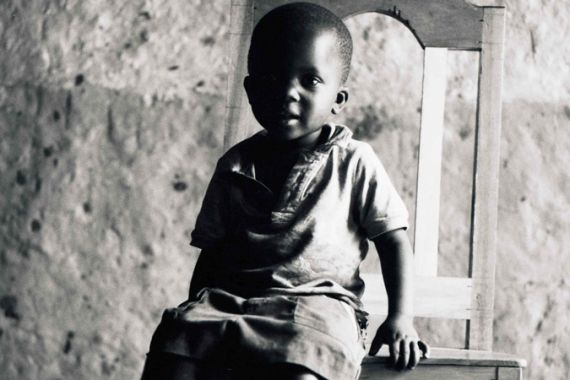

| Many women and children come to Masika’s centre as victims, blamed and rejected by their families [Fiona Lloyd-Davies] |

By Fiona Lloyd-Davies

Masika Katsuva is a tiny woman, barely five feet tall, but she has a giant of a personality. And she is getting cross with me. “Fiona, I don’t have time to sit and talk to you. If I don’t go out to the fields and get cassava we will all starve,” she says. “No problem,” I say, “I’ll come too.”

Keep reading

list of 4 itemsNigeria’s women drivers rally together to navigate male-dominated industry

Members of London’s Garrick Club vote to let women join for first time

Why has Australia declared a ‘national crisis’ over violence against women?

She puts her hoe into a large basket, strapping it to her head and sets off. Masika has made her home on the side of a main road in one of the most violent provinces in eastern Congo – South Kivu. The compound is open to the road. There is little shelter from the regular minibuses which hurtle past covering everything and everyone with a thin film of dust.

Goats and children are often hit, and recently-installed speed bumps have not prevented one of Masika’s rescued children – seven-year-old Vivienne – from becoming a casualty. She has lost her two front teeth and suffered a nasty bash to her head. Masika took her to hospital, but Vivienne is not her usual giggly self anymore.

‘Surviving hell on earth’

Even in the dry season eastern Congo is lush. Fields of maize, swaying in the breeze, grow higher than you have ever seen; ferocious electric storms, light up the night sky in pink and blue, quenching the thirst of the land with enormous raindrops. The abundance of everything is extreme, including the violence. Nearly six million people have died since the first war began in 1996. Hundreds of thousands of women, children and men have been raped. And it is still going on.

It is the people who bring me back time after time, people who simply do not give up despite surviving hell on earth. Masika has been raped four times by gangs of soldiers and militia – often because of her work saving other rape survivors. Vivienne is one of them, although she does not know she is the product of rape. After the rape, her mother’s family agreed to take her mother back, but refused Vivienne – she is a product of the enemy.

| “Most of them, when they come here, have never worked in a field before. But given what they’ve been through, being stigmatised and neglected … the field provides … hope for a better life”

Masika Katsuva |

Masika takes me off the main road and down a narrow path, under the glare of the intense sun. An elderly couple squeeze past us. The man holds a multi-coloured umbrella over his wife to shield her from the heat. Masika has no such protector. Her husband, who she calls the “love of her life”, was dismembered in front of her.

Out in the open, Masika stops by a field of crops, to catch her breathe and pick some small chilli peppers. Eating them raw she turns to me: “I never know when I may get my next meal,” she says.

We are in the middle of fields now, with crops either side of us. It is harvest time and patches of coloured material worn by women stand out amongst the green and yellow of the cassava and corn. Some are weeding, others with babies on their backs are breaking off the maize and putting it in baskets. They chat to each other. Occasionally you can hear them laughing.

Pointing to her right, Masika shows me a patch of uncultivated land. “We’ve just bought this field,” she says. “A woman of care gave us the money. In a few weeks we’ll come and prepare it for planting seeds.”

‘Mama Masika’

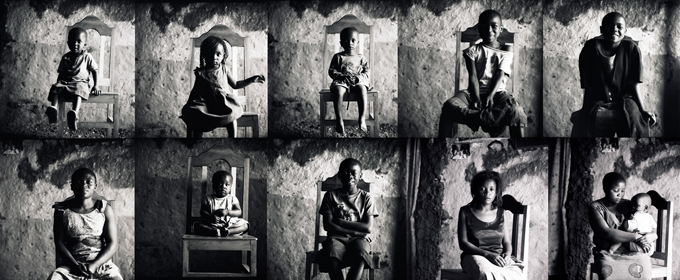

| Witness Extra | ||||||||||||

|

An American donor has given Masika some money to help provide for the women survivors she is looking after. At the moment there are 170 women. They all refer to her as Mama Masika. She provides them not just with the practical things they need, like medical treatment and a roof over their head. She also gives them inspiration to keep going. In the past ten years she has helped more than 6,000 rape survivors.

Most of the women and girls I spoke to at her centre told me the same thing; they had all thought of suicide. They had witnessed and survived terrible things, and then they had been rejected by their families or their communities. Those who had become pregnant still consider murdering their children.

Seventeen-year-old Odette was 13 when she was taken by militiamen. At their camp, deep in the forest, they put her in a hole in the ground for six months where she was raped constantly. She now has a four-year-old little boy, an angelic happy toddler, innocent of his mothers wish to kill him. She has been with Masika since she escaped and is desperate to finish school: “I want to be a lawyer,” she says, almost smiling.

“This is my personal field,” says Masika pointing to a patch of cassava trees growing up the side of a hill, “the one I use to feed everyone at the centre.” Some women greet her. “I’ve paid them to come and help me harvest,” Masika explains.

They have already piled up many roots for her to take home. She starts to load them up when her mobile phone rings. Everyone here is dependent on the mobile. It is virtually the only modern invention that works and keeps the country functioning, just. But it is bad news, Masika looks ashen. “The new baby is very ill – we must go back to the centre.”

Back at her house we found Espoire, an eight-month-old-baby, limp, virtually lifeless. Masika bathes him in cold water to bring his temperature down. One of the girls brings her bag, ready-packed to take to the hospital. This happens all the time. “I found Espoire in a village after an attack,” she tells me in the crew-car as I take them to hospital.

“The chief said that when the militia attacked they told the mothers to throw their babies in the pots and beat them to death like vegetables. When Espoire’s mother refused they shot her.” Masika found the baby with a broken arm and brought him home three months ago. “I am devoted to these babies,” she says. “I must help them survive. They keep me going.”