Profile: Greek PM George Papandreou

Besieged by economic chaos and furious demonstrators, the Greek prime minister faces an uncertain future.

|

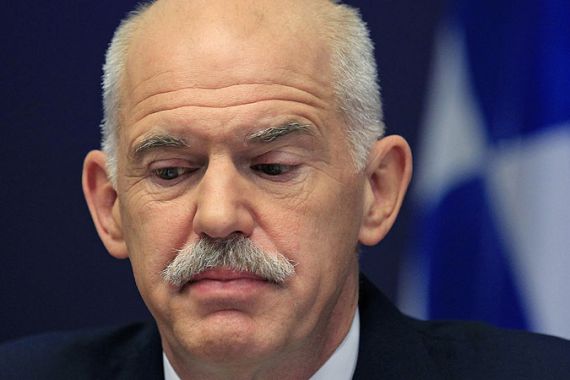

| Papandreou entered office to find that Greece’s deficit was more than twice as big as previously thought [Reuters] |

George Papandreou, whose job as Greek prime minister is on the line, was born into an illustrious political family.

Both his father, Andreas, and his grandfather, George Sr, also served as prime ministers of Greece.

But amid the tumult currently engulfing Greece in the wake of a worsening debt crisis, Papandreou’s family lineage may count for little in extending his own political life.

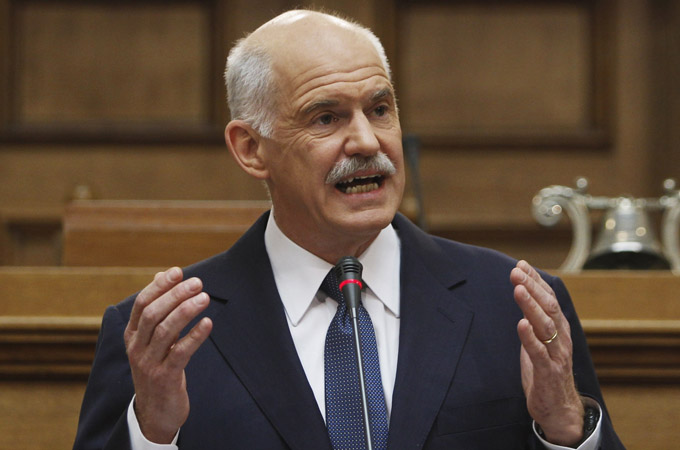

Papandreou’s stint as prime minister could end as early as Friday when he faces a parliamentary confidence vote. If he loses the vote, he would be forced to step down as prime minister.

Born in the US state of Minnesota in 1952, Papandreou reportedly speaks English better than Greek.

After studying sociology at Amherst College and the London School of Economics, and working as a fellow at Harvard, he moved to Greece when the military regime ruling the country fell in 1974.

He worked his way up through the ranks of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK) party, winning a seat in parliament.

Along with the centre-right New Democracy, the social democratic PASOK, founded by Papandreou’s father, is one of Greece’s two major political parties today.

In 1999, Papandreou was appointed as foreign minister, and helped improve Greece’s relations with neighbouring Turkey and Albania.

He also oversaw the country’s successful hosting of the 2004 Summer Olympics, the first games hosted by Greece in more than 100 years.

In February 2004, Papandreou was elected leader of PASOK.

Although he led his party to electoral defeat in both 2004 and 2007, PASOK won a sizable parliamentary majority in October 2009, just as Greece was hurtling towards financial crisis.

Mass strikes

On taking office, Papandreou soon discovered that the previous New Democracy-led government had grossly underestimated the size of the country’s deficit.

Previously thought to be six per cent of Greek GDP, it turned out that the country was actually running a deficit of more than 12.7 per cent of GDP.

This revelation caused investors to flee Greece, making it much more difficult for the country to borrow money on global financial markets.

As a result, Greece was forced in April 2010 to accept a $62bn bailout package from the European Union and the IMF in order to avoid defaulting on its debt.

In exchange for receiving bailout funds, the Greek government was required to implement tough economic austerity measures.

Although Papandreou promised not to raise taxes or cut wages in 2009, he has since reneged on this vow in an attempt to balance the country’s budget.

The austerity measures have led to mass strikes, riots and sit-ins in Athens’ Syntagma Square.

In an effort to avoid the political risks entailed by these policies, Papandreou unexpectedly announced on October 31 that Greece will hold a referendum in December to decide whether to accept a new bailout package.

Papandreou’s referendum will force the Greek people to decide whether or not to accept the strict austerity measures, a pre-condition of the bailout.

If the referendum fails, Greece could default on its debt and be forced to abandon the euro.