Men may not become extinct

New study rebuts “men-are-doomed” scenario which got traction when scientists found that male chromosome had shrivelled.

|

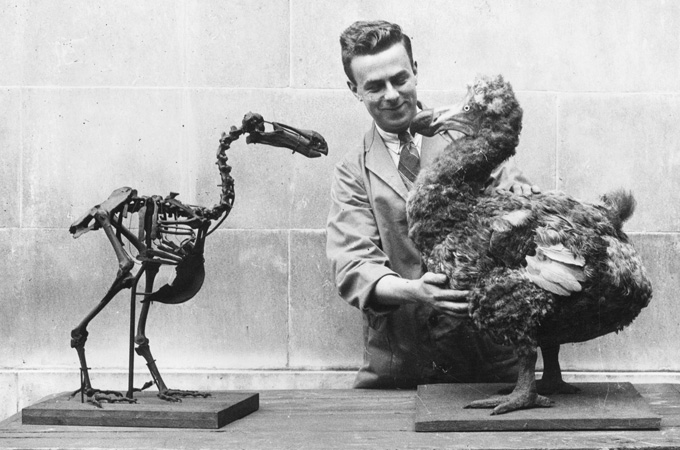

| Some theories said the Y-chromosome could go the way of the dodo bird and be extinct in just 125,000 years [Getty] |

Theories that men will eventually become extinct because the Y-chromosome is shrinking are quite wrong, says a new gene study.

Published on Wednesday, it said the chromosome which determines maleness has been stable for millions of years.

The “men-are-doomed” scenario leapt to prominence nearly a decade ago when scientists found that the male chromosome had dramatically shrivelled.

It had plummeted from a super-Y of more than 1,400 genes, several hundred million years ago, to a nubby little stump with just several dozen.

That discovery triggered opinion that the Y was headed for defeat.

We humans could end up like the Transcaucasian mole vole, according to one worrying thought.

A mammal whose Y chromosome has been routed by evolutionary pressure, the mole vole has differentiated into two species, one of which is Y-less. How the gender of its offspring is determined is a mystery.

In the worst scenario, men would disappear without some artificial means to keep the beleaguered male gender going.

Some doomsayers said this would happen in around five million years – others, in just 125,000 years – as the Y-chromosome went the way of the dodo.

But the latest study says the Y’s shrinkage occurred in the very distant past and the chromosome has been wonderfully stable for millions of years.

The human genome has 22 pairs of chromosomes plus one pair that determine sex.

If you are a female, you get two X chromosomes, and if you are male, it’s an X and a Y, whose all-important sex-determining region accounts for the sperm and testes.

‘The Y isn’t going anywhere’

The new evidence comes from a comparison of the human Y-chromosome with that of the rhesus macaque – a so-called Old World monkey whose evolutionary path diverged from humans and chimps some 25 million years ago.

The rhesus Y-chromosome has not lost a single ancestral gene in all this time, the study said.

By comparison, the human Y has lost one ancestral gene, occurring in a tiny segment that accounts for just three per cent of the entire chromosome.

“With no loss of genes on the rhesus Y and one gene lost on the human Y, it’s clear the Y isn’t going anywhere,” said Jennifer Hughes of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Her boss, David Page, said he had been fighting the notion of the “rotting Y” for the past 10 years and believed the new paper “simply destroys” the theory.

“I can’t give a talk without being asked by the disappearing Y,” he complained. “This idea has been so pervasive that it has kept us from moving on to address the really important questions about the Y.”

Before they became specialised sex chromsomes, the X and Y were essentially like ordinary chromosomes and used to swap genes with each other, a process called crossover that helps weed out harmful mutations and keeps the gene pool wide, according to Page’s team.

But the X-Y crossover stopped, causing the Y chromosome to swiftly lose hundreds of unwanted genes over five stages.

“Then it levelled off, and it’s been doing just fine since then,” said Page.